The steam hammer was developed in 1839 by the Scotsman James Nasmyth (also spelt Naysmyth, 1808-1890). Coming in a wide range of dimensions, the steam-powered machine was used to forge and shape very large pieces of metal for industrial use. Nasmyth made a fortune from an invention which became crucial to the larger engineering projects of the Industrial Revolution.

The Steam Engine

The invention of the steam engine was a process of several steps involving multiple inventors. In 1698, a steam-powered pump was invented by Thomas Savery (c. 1650-1715) which was designed to clear mine shafts of floodwater. In 1712, Thomas Newcomen (1664-1729) adjusted Savery's design to create a self-contained steam engine which was a lot more powerful. Next, James Watt (1736-1819) developed Newcomen's design, and by 1778, he had greatly reduced the fuel consumption of the steam engine and increased again its power. Engineers continued to improve the engine until it worked using a pressure high enough to create a power capable of moving great weights. The Scottish engineer James Nasmyth had the idea that such a power could be used in an industrial hammer to forge and bend large pieces of metal for use in the construction and manufacturing industry, even for new, more efficient steam engines.

Designing for Brunel

As was often the case during the Industrial Revolution, necessity was the mother of invention. James Nasmyth was encouraged to create his steam hammer because other engineers needed large metal pieces for their own inventions. Isambard Kingdom Brunel (1806-1859), a key figure in this rapid period of industrialisation, was busy with all kinds of projects, but one of them, in particular, would benefit from the steam hammer. Brunel was building giant steamships like the SS Great Western and SS Great Britain, completed in 1838 and 1843, respectively. The latter ship's design was innovative since it had a propellor-driven power source, but back in 1839, when still in the planning stage, Brunel was focussing on using only giant paddle wheels, which needed metal drive shafts around 76 cm (30 in) in diameter. At the time, there was no existing forge or machine tool big enough to create such metal pieces for heavy industry. Brunel wrote to his friend Nasmyth, a machine tool specialist already supplying many parts for the Great Britain project, in the hope of finding a solution. As the history of metalworking is now fully aware, Nasmyth and his workshop team were up to the challenge.

James Nasmyth

Nasmyth had been tinkering with steam engines for most of his life, including in his childhood in Edinburgh when he built small working models. James' father Alexander, known primarily as an artist, was also interested in engineering and even had a forge in the family home. James gained invaluable practical experience when he worked in the famous engineering workshop of Henry Maudslay (1771-1831) in London. Maudslay had invented the metal precision lathe amongst other innovations, and he was the man to be associated with for any self-respecting engineer of the period. Nasmyth loved machines, but he was no idealist trying to create a better world. Rather, he was the personification of the spirit of the Industrial Revolution, constantly enquiring how a process could be made more efficient by "reducing labour costs and dependency on unreliable working men" (Waller, 45). As Nasmyth himself put it, "[machines] were always ready for work, and never required a holiday" (ibid, 113).

Moving on to Manchester, Nasmyth established his own foundry in August 1836. The canny Nasymth made sure his Bridgewater Foundry had a perfect location near a canal, railway, and road to easily distribute his locomotives, machines, tools, and metal products. Here he manufactured a wide variety of precision machine tools and 109 steam locomotives over the next two decades, including 20 for Brunel's Great Western Railway Company. Nasmyth was not satisfied, though, and kept on inventing. He was extremely well-connected thanks to his family and his own endeavours. It was relatively easy to gain funding from venture capitalists eager to increase their fortunes in new technology, and Nasmyth looked like a man capable of coming up with a real money-winner. The timing was right, too, as mechanised industries – textiles, mining, and railways – were all booming thanks to the steam engine and the demand for tools, in particular, was insatiable.

Nasmyth noted to his business partner Holbrook Gaskell that, "These are indeed glorious times for engineers. I never was in such a state of bustle in my life…such quantity of people come knocking at my little office door from morning til night" (Waller, 106). The engineer had grasped early one of the key principles of the Industrial Revolution: use machines to create tools, which could create better tools, which could create better machines. Around 1839, Nasmyth found his golden goose, the steam hammer.

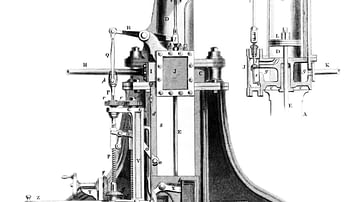

The Mechanism

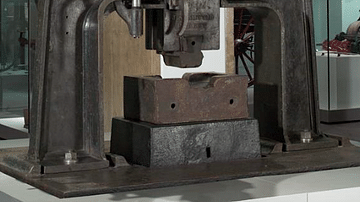

The principle of Nasmyth's hammer was that a steam engine (which used the expansion of heated water to drive a piston and rod mechanism) raised a large weight and then dropped it vertically on the metal to be bent, usually iron or steel. In addition, the metal could simply be pounded while still red hot to remove as many impurities as possible. The metal to be worked rested on an anvil block with an adjustable anvil plate that could be used to give the pressed metal the desired form. The early models merely lifted a great weight and dropped it, but refinements were soon made, notably by Nasmyth's foundry manager Robert Wilson. Crucially, the new machine used control gears to manage the speed of the descent of the weight. It could also move the weight with precision since it followed guides on its descent. These fine controls allowed any number of pieces of metal to be bent in exactly the same way, important for constructing large metal objects made up of uniform composite pieces like a boiler engine. At the other end of the scale, as Nasmyth was fond of demonstrating to visitors to his foundry, the delicate precision the hammer was capable of meant a 2.5-ton weight could crush an eggshell sitting in a wine glass and do no harm to the glass. All of this could be done by one man casually operating a simple lever. Some hammers could deliver 220 blows every minute. The steam hammer was a giant leap forward compared to the low power, slow, and general inaccuracy of the old heavy hammers operated by water wheels.

Nasmyth patented his invention in 1842 after he visited the Le Creusot works in France and saw his design in full working action (there is some debate as to whether the French company had copied Nasmyth's early drawings or had developed their own steam hammer completely independently). In any case, once a machine was out in the working world, it was inevitable that engineers would add their own refinements to it. Further development's in the steam hammer's design made sure that steam from the engine was used not only to lower the weight but also to push it down. This almost tripled the power of the machines and the range of metal pieces they could manipulate. Industry loved them, and in Britain at least, Nasmyth cornered the market. Very often customers, having bought one or two, came back to order more. Nasmyth's foundry churned out 493 steam hammers between 1843 and 1856, by far the Scotsman's bestselling product.

Uses of the Steam Hammer

The cast iron and steel hammer could be used for all sizes of objects from the very large, like bridge girders, to the very small, like coins. Brunel changed his mind and ditched the paddle wheels for SS Great Britain, but plenty of others were interested in Nasmyth's machine. Some of the most famous companies in Britain were buying steam hammers, from the Great Western Railway Company to Stephenson & Co., manufacturers of Stephenson's Rocket. From around 1850, the Royal Mint used a steam hammer to manufacture coins, and this machine certainly had longevity, remaining in use until 1933. Heavy weapons manufacturing was another industry that needed the steam hammer's capabilities, and Nasmyth won a lucrative contract with the Woolwich Arsenal. The dockyards of the Royal Navy bought 11 steam hammers from the Bridgewater Foundry to build their warships. The famous printing firm De La Rue, which produced the country's banknotes, was another customer. Nasmyth realised the value of demonstration and good marketing. He knew his giant hammers were impressive to behold and was never shy of a photo opportunity; he often, too, hosted distinguished visitors to his foundry, including foreign dignitaries like the Grand Duke of Russia and the Rajah of Sarawak.

Hammers were adapted for new uses, too, for example, to drive piles into the ground on construction projects. As heavy industry diversified and trains, ships, and armaments grew ever bigger and more numerous, more and more steam hammers were made to bigger and more varied specifications. Steam hammers grew to a prodigious size, some were over 10.6 metres (35 ft) tall and weighed 90 tons, which meant they created a massive amount of noise that could be heard across towns. Certainly, they were a wonder, and it is no surprise that a Nasmyth steam hammer was a giant attraction at the Great Exhibition of 1851 in the Crystal Palace in London. The machine was one of the show's prize winners.

Besides steam hammers and locomotives, Nasmyth's company went on to build drills, punching machines, and presses for use all over the world before he retired early having made himself a fortune. Nasmyth spent his retirement in rural Kent, where he named his huge mansion Hammerfield. Nasmyth also had a coat of arms made for himself which, inevitably, included a hammer. The ever-curious inventor devoted himself to other interests, particularly astronomy and the study of the Moon, which he spied through sophisticated telescopes he himself had made. Nasmyth died on 7 May 1890 in London, and his ashes were sent to Scotland. Bizarrely, for a man who left behind a £250,000 fortune (over £24 million or $29 million today), Nasmyth's heirs had his remains transported by train in a plain paper bag to avoid paying the higher charge such things usually cost. Perhaps the reason was Nasmyth had left the bulk of his estate to fund various charitable organisations. In recognition of his contribution to lunar studies, a crater on the Moon is named after Nasmyth.