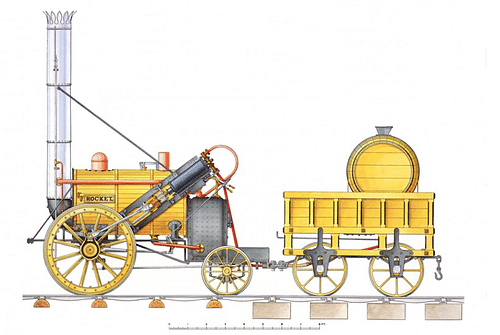

The Rocket was a pioneering steam-powered locomotive invented in 1829 by the British engineer Robert Stephenson (1803-1859). For a cash prize, extensive competition trials were held to find the best locomotive in the Rainhill Trials. Rocket won and so was used to pull carriages on the first inter-city train line from Liverpool to Manchester, which opened in September 1830.

The Steam Engine

The steam engine was perhaps the most important invention of the Industrial Revolution. It began as a steam-powered pump invented by Thomas Savery (c. 1650-1715) and patented in 1698. Thomas Newcomen (1664-1729), an ironmonger in Dartmouth, adjusted Savery's design and greatly increased the power. Newcomen's steam engine pump was first used in a coal mine in Dudley in the Midlands in 1712. The next leap forward came thanks to the Scottish instrument worker James Watt (1736-1819), who, by 1778, had greatly reduced the fuel consumption of his machine. As the steam engine continued to evolve to create a high-pressure power source, so the possibilities of what such a machine could be used for grew.

In 1801, Richard Trevithick (1771-1833) invented the first steam-powered vehicle. Trevithick's machine was pretty good, but his real problem was the poor condition of roads at that time. The inventor solved the problem in 1803 by having his vehicle run on purpose-built tracks of its own. The idea of a steam-powered train was born.

Investors saw the potential to challenge the dominance of river and canal boats as Britain's primary means of goods transportation and stagecoaches for passenger transport. Canals were expensive to dig, canal boats were limited in the weight of goods they could transport, and negotiating gradients via canal locks was time-consuming. The time it took to transport goods by sea was satisfactory, but then getting them from major ports to other urban areas was slow and expensive, as this 1830 quote from The Observer newspaper highlights: "Goods would arrive in a shorter time from New York to Liverpool than they could afterwards be conveyed from Liverpool to Manchester." The average speed of a canal boat on its journey from one destination to another was around 4.8 km/h (3 mph). Steam-powered vehicles seemed to offer much more speed and, therefore, great savings in costs. At the same time, stagecoaches were very slow and very uncomfortable for private travellers. What was really needed to revolutionise both of these traditional areas of transportation was a more powerful and reliable locomotive than Trevithick's.

Stephenson & Co.

Up stepped a brilliant father and son team: George Stephenson (1781-1848) and Robert Stephenson, both professional engineers. In 1823, they set up their own company Stephenson & Co., which focussed on locomotives for use in coal mines to transport coal short distances at the coalfield. On 27 September 1825, George Stephenson successfully ran his Locomotion 1 train engine. This train transported the first railway passengers from Stockton to Darlington in the northeast of England. The success meant other, larger towns and cities were keen to build their own, more ambitious railway lines. The race was on to see who could come up with the best train for such projects. George Stephenson was already employed as the chief engineer for the Stockton and Darlington Railway, and Robert Stephenson had been tinkering with engines all his life. The Stephensons, and particularly Robert, were keen to show they could design the best locomotive in Britain, and it was a cause they believed in absolutely. Robert Stephenson once said: "...rely upon it, locomotives shall not be cowardly given up. I will fight for them until the last. They are worthy of a conflict."

The Rainhill Trials

Robert Stephenson tested his latest invention at the Rainhill Trials held at Rainhill between Liverpool and Manchester in October 1829. The trials were a competition designed to find the best locomotive for use on the new railway line planned to connect these two cities. It was the directors of the Liverpool & Manchester Railway Company (L&MR) who organised the competition. The machines of the entrants had to be self-propelling and capable of pulling several carriages. To encourage participants, a very handsome cash prize of £500 was on offer to the winning locomotive (around £42,000 or $50,000 today). The incentive worked since ten inventors promised to attend, even if only six actually made it with their fantastic machines.

One entry, Cyclopede, was actually powered by two horses standing on a drive belt to make the wheels move below and so was not really in the running. Cycolpede's effort came to an ignominious end when a horse fell through the contraption. Another entrant used an adapted engine taken from a stagecoach and so did not have the power to compete with the others. The third wonderful but weird locomotive to fail was a carriage operated by the muscle power of two men. This device was quite a sight but no good for a future train line operator. As a consequence of these fallouts, the trials essentially became a three-horse race.

The rules for the competition in terms of design specifications were a little vague at first. Limitations included a total budget cost of no more than £550 to build the locomotive and that the steam engine use pressure no greater than 50 pounds per square inch. Each locomotive had to perform ten return trips along a specially-built section of railway tracks 2.4 kilometres (1.5 mi) long. A certain weight had to be pulled, up to 20 tons, to simulate passenger carriages and freight. To make sure the locomotives were reliable, they all had to refuel and then do the ten return legs all over again. The minimum expected speed was 16 km/h (10 mph). The L&MR directors generously supplied all the necessary coal for the trials.

A panel of three expert judges watched the proceedings and took copious notes. Speed and the time taken to complete the runs were not the only things the judges were looking at. It was important how consistent the locomotive was, its reliability, pulling power, and total consumption of fuel and water over the trials. The nine-day trials captured the imagination of the press and the public alike. Over 10,000 people came to watch, and many placed bets on the locomotive they thought would win.

The Rocket's Design

The three serious competitors for the prize were Novelty, Sans Pareil and Robert Stephenson's Rocket. Novelty was the fastest of the three but was let down by reliability problems and could not complete the trials when a boiler joint was blown out. It did not inspire confidence with its appearance either, looking something like a steam engine stuck on a cart. Sans Pareil (from the French word meaning "without equal") was designed by Timothy Hackworth (1786-1850). It was a good locomotive, although not quite as innovative as Rocket. Certainly, Stephenson saw Hackworth as his main rival, but he need not have worried as Sans Pareil was discovered to be over the competition weight limit of six tons. The locomotive was allowed to run anyway but disqualified from the cash prize.

Rocket was built in Newcastle at the Stephenson's company works. The machine used four wheels powered by the steam engine which burnt coal as fuel and which consumed freshwater provided in a tank. The locomotive was not an entirely new design as such but an assemblage of existing ideas with some important tweaks that created a new package of technology. This was the genius of Stephenson. One of the key innovations was actually the idea of Henry Booth (1788-1869), a L&MR director, which was to use not the usual single flue between the firebox and chimney but many narrow fire tubes, later called a multi-tubular boiler. Rocket's blast pipe was another step forward because it created an ascending current, which gave the engine more power by intensifying the steam. In theory, Rocket's self-regulating engine made it more efficient and more powerful than any locomotive yet seen. But would it work in practice? Stephenson was confident. In a homage to the stagecoaches he hoped to put out of business, the 4.3-ton Rocket was painted yellow and black.

Rocket, when unfettered by any carriages, reached a top speed of at least 48 km/h (30 mph), otherwise, its average speed during the trials was a more modest 19.3 km/h (12 mph) when pulling around 12 tonnes (the organisers had reduced the original competition tonnage as they wanted to see the possible speed of a passenger-only service). Today these speeds are unimpressive, but at the time, they were a great leap forward, and those watching the trials were astonished at the speed such hulking great piles of metal could achieve. Rocket was a success.

The First Inter-City Railway

The owners of the L&MR commissioned the Stephensons for four more engines, which were improved adaptations of Rocket. L&MR also bought Sans Pareil for £550 and put it into service. The Liverpool-Manchester line, the first inter-city service, opened on 15 September 1830 in the presence of no less a personage than a great war hero: the Duke of Wellington. A passenger on one of the pre-launch publicity runs, the actress Fanny Kemble, gave the following equestrian-type description of the experience in a letter to a friend:

We were introduced to the little engine which was to drag us along the rails. She (for they make these curious little fire-horses all mares) consisted of a boiler, a stove, a small platform, a bench, and behind the bench a barrel containing enough water to prevent her being thirsty for fifteen miles, – the whole machine not bigger than a common fire-engine. She goes upon two wheels, which are her feet, and are moved by bright steel legs called pistons ... the coals, which are its oats, were under the bench, and there was a small glass tube affixed to the boiler, with water in it, which indicates its fulness or emptiness when the creature wants water, which is immediately conveyed to it from its reservoirs ...This snorting little animal, which I felt rather inclined to pat, was then harnessed to our carriage, and Mr Stephenson having taken me on the bench of the engine with him, we started at about ten miles an hour. (Dugan, 11)

The line was a roaring success and soon carried 1,200 passengers every day. The Rocket-powered trains travelled at 40 km/h (25 mph) and carried goods besides people. This was, indeed, a new beginning for transport.

Railway Mania

Rocket was rebuilt in 1831, using new innovations in locomotive design, but it was obsolete within a decade as train engines became ever larger, more powerful, and faster. The railway lines spread quickly, too. In 1838, Birmingham was connected to London, and in 1841, passengers could take the train from the capital to Bristol. The iron tracks spread so quickly across Britain, the phenomena became known as 'railway mania'. By 1870, there were over 24,000 kilometres (15,000 mi) of rail lines. The idea spread around the world; the first working railway line in the United States was established in 1833 and connected New York to Philadelphia. By 1875, the USA had three and a half times the rail tracks that Britain had. For many destinations, no longer did passengers have to brave the slow and uncomfortable horse-drawn carriages that had previously been the only means of travelling long distances over land. Speed and comfort were now the expectations of travellers.

Robert Stephenson continued his successful career in railways, diversifying his engineering skills to build several bridges, amongst which was the Britannia bridge in North Wales. Stephenson's Rocket used to be on display in the Science Museum in London, but it is currently on a 10-year loan to the National Railway Museum in York (2019-2029). There is also a working replica in this museum.