The Stono Rebellion (also known as Cato's Rebellion or Cato's Conspiracy, 9 September 1739) was the largest slave revolt in the British colonies of North America. Led by an educated slave, Cato (also known as Jemmy), enslaved Black people attempted to flee from South Carolina to freedom in Spanish Florida but were caught and defeated by local militia.

Cato and others of the initial group of 22 were taken from the Kingdom of Kongo (modern Angola and DR of Congo), which supported a lucrative slave trade. Rulers of the Kingdom of Kongo in the 16th and 17th centuries kept a standing army of slaves, and it is thought that Cato and the others were former soldiers who had been captured after an engagement and sold into slavery.

How long Cato had been a slave is unknown, but the rebellion was later blamed on a recent influx of slaves from Africa, so it is likely he had not been enslaved long (though this is speculation). The revolt, blamed on this arrival of enslaved African soldiers, caused South Carolina to close its ports at Charleston to slave-trafficking ships for the next ten years and also led to the passage of the Negro Act of 1740 restricting slaves' lives further, prohibiting literacy among the slave population, and forbidding the freeing of slaves by their masters.

The Stono Rebellion may have inspired later revolts, including Gabriel's Rebellion (1800), the 1811 German Coast Uprising, Denmark Vesey's Conspiracy (1822), and Nat Turner's Rebellion of 1831. Even if it had nothing to do with any later uprisings, the Stono Rebellion is important in its own right as a strike against the institution of slavery and a stand for individual and collective liberty.

Background

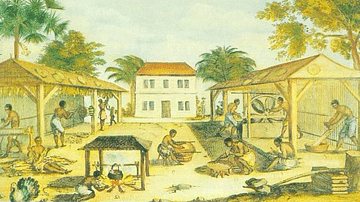

Florida was claimed by Spain after Juan Ponce de León 'discovered' it in April 1513, and by 1559, large regions had been colonized by Spanish settlers. The English established the Jamestown colony of Virginia in 1607 and the colony of Carolina in 1663. When residents of Virginia objected to the political-social organization of Carolina – which included large plantations of cash crops such as cotton, rice, and tobacco and the political supremacy of large plantation owners – the colony was divided into North Carolina and South Carolina (the northern colony to serve as a buffer), both of which imported slaves.

Georgia was established by the anti-slavery reformer James Oglethorpe (l. 1696-1785) in 1733 and rejected large plantation farming and the institution of slavery that made it possible. To keep peace with South Carolina, however, Georgia allowed slave-catchers pursuing runaways to operate in their territory. If a slave in South Carolina wanted to escape to freedom, the only way was down through Georgia to Spanish Florida, evading slave-catchers the entire time.

Florida welcomed escaped slaves, who, as long as they converted to Catholicism and served in the local militia, were granted their freedom. In 1738, Fort Mose was established near St. Augustine and garrisoned by escaped slaves, becoming the first legally recognized free Black settlement in North America. Florida sent out riders with written proclamations inviting any and all slaves to throw off their chains and make their way south to freedom.

The Revolt

By 1708, the enslaved Black community of South Carolina outnumbered the White population, and there were concerns over a slave uprising aided by the Native Americans of the region. Scholar Alan Taylor describes how the authorities of South Carolina enacted a policy of 'divide and conquer' to keep the peace:

Carolina's early leaders concluded that the key to managing the local Indians was to recruit them as slave catchers by offering guns and ammunition as incentive…to pay for the weapons, the native clients raided other Indians for captives to sell as slaves – or they tracked and returned runaway Africans.

(228)

Still, by 1739, fears of a general uprising persisted, encouraging the passage of the Security Act of 1739, requiring all White men to attend church armed. On Sundays, slaves were allowed to tend to their own gardens and go about their own business, and so, it seems to have been thought, the White populace should be armed especially on that day in case the slaves revolted. The Security Act had not been passed yet in early September 1739, but even if it had, it would have done nothing to prevent the Stono Rebellion because all the armed White citizens would have been in church with their weapons when Cato gathered the other 22 rebels at the Stono River.

Although Cato's plans are unknown, it is believed he was leading his people on the 150-mile (240-km) journey from the Stono River to Florida, probably to the Fort Mose community. Slave-catchers would be deterred by the strength in numbers of the rebels.

The details of the Stono Rebellion are given below in two accounts, one by an anonymous White writer of the time – An Account of the Negroe Insurrection in South Carolina, 1739 and A Family Account of the Stono Uprising, ca. 1937, given by a descendant of Cato.

Text

The following is taken from Two Views of the Stono Slave Rebellion, South Carolina, 1739, as published by the National Humanities Center Resource Toolbox: Becoming American: The British Atlantic Colonies, 1690-1763 cross-checked with the same documents in Stono: Documenting and Interpreting a Southern Slave Revolt (2005) by Mark M. Smith.

An Account of the Negroe Insurrection in South Carolina, 1739

Sometime since there was a Proclamation published at Augustine, in which the King of Spain (then at Peace with Great Britain) promised Protection and Freedom to all Negroes Slaves that would resort thither. Certain Negroes belonging to Captain Davis escaped to Augustine and were received there. They were demanded by General Oglethorpe who sent Lieutenant Demere to Augustine, and the Governour assured the General of his sincere Friendship, but at the same time showed his Orders from the Court of Spain, by which he was to receive all Runaway Negroes.

Of this other Negroes having notice, as it is believed, from the Spanish Emissaries, four or five who were Cattel - Hunters, and knew the Woods, some of whom belonged to Captain Macpherson, ran away with His Horses, wounded his Son and killed another Man. These marched for Georgia, and were pursued, but the Rangers being then newly reduced [sic] the Country people could not overtake them, though they were discovered by the Saltzburghers, as they passed by Ebenezer. They reached Augustine, one only being killed and another wounded by the Indians in their flight. They were received there with great honours, one of them had a Commission given to him, and a Coat faced with Velvet.

Amongst the Negroe Slaves there are a people brought from the Kingdom of Angola in Africa, many of these speak Portuguese [which Language is as near Spanish as Scotch is to English,] by reason that the Portuguese have considerable Settlement, and the Jesuits have a Mission and School in that Kingdom and many Thousands of the Negroes there profess the Roman Catholic Religion. Several Spaniards upon diverse Pretences have for some time past been strolling about Carolina, two of them, who will give no account of themselves have been taken up and committed to jail in Georgia.

The good reception of the Negroes at Augustine was spread about, several attempted to escape to the Spaniards, & were taken, one of them was hanged at Charles Town. In the latter end of July last Don Pedro, Colonel of the Spanish Horse, went in a Launch to Charles Town under pretence of a message to General Oglethorpe and the Lieutenant Governour.

On the 9th. day of September last being Sunday which is the day the Planters allow them to work for themselves, Some Angola Negroes assembled, to the number of Twenty; and one who was called Jemmy was their Captain, they surprised a Warehouse belonging to Mr. Hutchenson at a place called Stonehow [Stono]; they there killed Mr. Robert Bathurst, and Mr. Gibbs, plundered the House and took a pretty many small Arms and Powder, which were there for Sale. Next, they plundered and burnt Mr. Godfrey's house, and killed him, his daughter and son.

They then turned back and marched Southward along Pons Pons, which is the Road through Georgia to Augustine, they passed Mr. Wallace's Tavern towards daybreak, and said they would not hurt him, for he was a good Man and kind to his Slaves, but they broke open and plundered Mr. Lemy's House, and killed him, his wife and Child. They marched on towards Mr. Rose's resolving to kill him; but he was saved by a Negroe, who having hid him went out and pacified the others.

Several Negroes joined them, they calling out Liberty, marched on with Colours displayed, and two Drums beating, pursuing all the white people they met with, and killing Man Woman and Child when they could come up to them. Colonel Bull, Lieutenant Governour of South Carolina, who was then riding along the Road, discovered them, was pursued, and with much difficulty escaped & raised the Country.

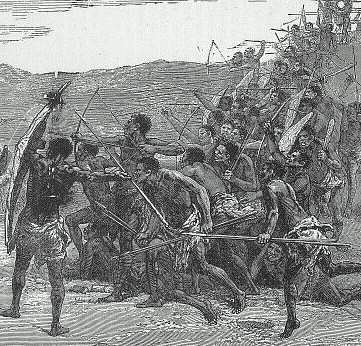

They burnt Colonel Hext's house and killed his Overseer and his Wife. They then burnt Mr. Sprye's house, then Mr. Sacheverell's, and then Mr. Nash's house, all lying upon the Pons Pons Road, and killed all the white People they found in them. Mr. Bullock got off, but they burnt his House, by this time many of them were drunk with the Rum they had taken in the Houses. They increased every minute by new Negroes coming to them, so that they were above Sixty, some say a hundred, on which they halted in a field, and set to dancing, Singing and beating Drums, to draw more Negroes to them, thinking they were now victorious over the whole Province, having marched ten miles & burnt all before them without Opposition, but the Militia being raised, the Planters with great briskness pursued them and when they came up, dismounting; charged them on foot.

The Negroes were soon routed, though they behaved boldly several being killed on the Spot, many ran back to their Plantations thinking they had not been missed, but they were there taken and Shot, Such as were taken in the field also, were after being examined, shot on the Spot, And this is to be said to the honour of the Carolina Planters, that notwithstanding the Provocation they had received from so many Murders, they did not torture one Negroe, but only put them to an easy death.

All that proved to be forced & were not concerned in the Murders & Burnings were pardoned, And this sudden Courage in the field, & the Humanity afterwards hath had so good an Effect that there hath been no farther Attempt, and the very Spirit of Revolt seems over. About 30 escaped from the fight, of which ten marched about 30 miles Southward, and being overtaken by the Planters on horseback, fought stoutly for some time and were all killed on the Spot. The rest are yet untaken.

In the whole action about 40 Negroes and 20 whites were killed. The Lieutenant Governour sent an account of this to General Oglethorpe, who met the advices on his return from the Indian Nation. He immediately ordered a Troop of Rangers to be ranged, to patrol through Georgia, placed some Men in the Garrison at Palichocolas, which was before abandoned, and near which the Negroes formerly passed, being the only place where Horses can come to swim over the River Savannah for near 100 miles, ordered out the Indians in pursuit, and a Detachment of the Garrison at Port Royal to assist the Planters on any Occasion, and published a Proclamation ordering all the Constables &ca. of Georgia to pursue and seize all Negroes, with a Reward for any that should be taken. It is hoped these measures will prevent any Negroes from getting down to the Spaniards.

A Family Account of the Stono Uprising, ca. 1937

George Cato, a Negro laborer, residing at the rear of 1010 Lady Street, Columbia, S.C., says he is a great-great-grandson of the late Cato slave who commanded the Stono Insurrection in 1739, in which 21 white people and 44 Negroes were slain. George, now 50 years old, states that this Negro uprising has been a tradition in his family for 198 years. When asked for the particulars, he smiled, invited the caller to be seated, and related the following story:

"Yes, sah! I sho' does come from dat old stock who had de misfortune to be slaves but who decide to be men, at one and de same time, and I's right proud of it. De first Cato slave we knows 'bout, was plum willin' to lay down his life for de right, as he see it. Dat is pow'ful fine for de Catoes who has come after him. My granddaddy and my daddy tell me plenty 'bout it, while we was livin' in Orangeburg County, not far from where de fightin' took place de long ago.

"My granddaddy was a son of de son of de Stono slave commander. He say his daddy often take him over de route of de rebel slave march, dat time when dere was sho' big trouble all 'bout dat neighborhood. As it come down to me, I thinks de first Cato take a darin' chance on losin' his life, not so much for his own benefit as it was to help others. He was not lak some slaves, much 'bused by deir masters. My kinfolks not 'bused. Dat why, I reckons, de captain of de slaves was picked by them. Cato was teached how to read and write by his rich master.

"How it all start? Dat what I ask but nobody ever tell me how 100 slaves between de Combahee and Edisto rivers come to meet in de woods not far from de Stono River on September 9, 1739. And how they elect a leader, my kinsman, Cato, and late dat day march to Stono town, break in a warehouse, kill two white men in charge, and take all de guns and ammunition they wants. But they do it. Wid dis start, they turn south and march on.

"They work fast, coverin' 15 miles, passin' many fine plantations, and in every single case, stop, and break in de house and kill men, women, and children. Then they take what they want, 'cludin' arms, clothes, liquor, and food. Near de Combahee swamp, Lieutenant Governor Bull, drivin' from Beaufort to Charleston, see them and he smell a rat. Befo' he was seen by de army, he detour into de big woods and stay 'til de slave rebels pass.

"Governor Bull and some planters, between de Combahee and Edisto [rivers], ride fast and spread de alarm and it wasn't long 'til de militiamen was on de trail in pursuit of the slave army. When found, many of de slaves was singing' and dancin' and Capt. Cato and some of de other leaders was cussin' at them sumpin awful. From dat day to dis, no Cato has tasted whiskey, 'less he go against his daddy's warnin'. Dis war last less than two days but it sho' was pow'ful hot while it last.

"I reckon it was hot, 'cause in less than two days, 21 white men, women, and chillun, and 44 Negroes, was slain. My granddaddy say dat in de woods and at Stono, where de war start, dere was more than 100 Negroes in line. When de militia come in sight of them at Combahee swamp, de drinkin dancin' Negroes scatter in the brush and only 44 stand deir ground.

"Commander Cato speak for de crowd. He say: 'We don't lak slavery. We start to join de Spanish in Florida. We surrender but we not whipped yet and we is not converted.' De other 43 men say: 'Amen.' They was taken, unarmed, and hanged by the militia. Long befo' dis uprisin', de Cato slave wrote passes for slaves and do all he can to send them to freedom. He die, but he die for doin' de right, as he see it."

Conclusion

Casualties of the rebellion are unknown. The usual count of 47 enslaved people and between 23-28 Whites is understood as too low. The fate of Cato/Jemmy is also unknown. He was most likely killed in the attack by Bull, after which the militia beheaded the corpses and planted them on stakes along the road as a warning to others. Perhaps Cato's head was among these – or perhaps he escaped and made his way to Florida.

The most immediate response to the Stono Rebellion was passage of the Negro Act of 1740, which restricted the lives of slaves in South Carolina even more than they already were. Teaching a slave to read and write was criminalized since it was understood that Cato had been literate, slaves could no longer freely assemble or tend their own gardens, and masters could no longer privately free their slaves – that act had to be brought before a legislative council.

The Negro Act of 1740 also included measures to make the lives of slaves easier, but these were essentially meaningless. The 'school' created for slaves was simply indoctrination into a slaveholder's interpretation of Christianity, impressing on the 'students' that it was God's will they were slaves. Among the other measures were prohibitions against masters or overseers working slaves too hard or beating them too severely; but, because a slave's testimony was inadmissible, there was no way to enforce this.

Daily life for the slaves of South Carolina was made worse by the Stono Rebellion, but the measures taken by the authorities inspired more people to recognize the immorality and evil of the institution of slavery and strengthened the slaves' resistance to it, garnering greater support for abolition.