The Sugar Act of 1764, also known as the American Revenue Act, was legislation passed by the Parliament of Great Britain on 5 April 1764 to crack down on molasses smuggling in the American colonies and to raise revenue to pay for the colonies' defense. The act was unpopular and helped lead to the American Revolution (c. 1765-1789).

In the aftermath of the French and Indian War (1754-1763), the British Empire found itself in possession of large swathes of new colonial territory it had to defend. To reduce conflicts between American colonists and Native Americans such as the recent Pontiac's Rebellion (1763-1764), Parliament decided to send an army of 10,000 soldiers to defend the colonies. However, the upkeep of such an army would be expensive, and Parliament was currently struggling with mountains of postwar debt. Since the army was being sent for the defense of the American colonies, British Prime Minister George Grenville decided that the colonists should help pay the bill and devised the Sugar Act for this purpose.

The Sugar Act was an extension of the Molasses Act of 1733; it reduced the tax on molasses from 6 pence per gallon to 3 pence but restricted the trade of other valuable goods and placed harsh penalties on anyone convicted of smuggling molasses. Molasses was an important part of the colonial economy, especially in New England, and was a valuable commodity in the triangular trade; for these reasons, colonial merchants resisted the Sugar Act. Other colonists argued that the Sugar Act infringed on their liberties, such as the right of the American colonies to tax themselves, giving rise to the famous slogan 'no taxation without representation'. The Sugar Act was ultimately replaced in 1766, but Parliament continued to impose taxes on the colonies, inadvertently paving the way for the American Revolution.

A Question of Defense

In February 1763, as the long and hard-fought French and Indian War came to an end, the British Empire reaped the fruits of victory. The vanquished Kingdom of France was forced to cede control of Canada and all its colonial holdings east of the Mississippi River to Britain, greatly expanding Britain's territory in North America. However, this sudden increase in colonial possessions naturally produced a new set of problems that the British would have to deal with, particularly regarding defense. With the acquisition of Canada came tens of thousands of French-Canadian subjects whose loyalty was doubtful at best, seeing as they had all too recently been Britain's enemies. The presence of Spain in Louisiana and west of the Mississippi was also worrisome, as the Spanish were considered even more untrustworthy than the French.

But what was more troubling to British officials was the conflicts between American settlers and displaced Native Americans. As more white colonists moved into the lands that Britain had won from France, they naturally began fighting with the Native peoples of North America that lived there. Hoping to limit this bloodshed, King George III of Great Britain (r. 1760-1820) issued a Royal Proclamation on 7 October 1763 that forbade American colonists from settling the lands between the Appalachian Mountains and the Mississippi River. But of course, this proclamation went largely ignored, as a steady stream of white settlers continued to file into these lands. In May 1763, the Native Americans rose in revolt; led by the Odawa Chief Pontiac, they raided settlements in Virginia, Maryland, and Pennsylvania and captured all western British forts except for Detroit. Pontiac's Rebellion was quelled by the end of 1764 by British regular troops and American militia, but it served as a reminder to British officials that more of an effort would have to be made to keep the peace in the colonies.

So, the decision was made by British Prime Minister George Grenville (l. 1712-1770) to send a standing army to defend the American colonies and check the illegal westward expansion. But the upkeep of such an army would undoubtedly be costly, an uncomfortable fact for the British Parliament, which had accrued mountains of debt fighting the Seven Years' War. Since the troops were being sent to North America primarily to defend the colonies, Grenville and his supporters believed it only right that the American colonists footed part of the bill. Of course, Parliament would pay the majority of the annual £200,000 necessary to keep twenty battalions (or 10,000 men) in America, so it did not occur to many officials that there would be much of an issue.

Reviving the Molasses Act

In order to raise this revenue, Grenville proposed to extend and modify the Molasses Act of 1733, which was set to expire in 1763. The Molasses Act was a tax imposed on molasses imports from non-British territories, set at six pence per gallon. This tax had, of course, been unpopular amongst colonial merchants; instead of paying the required duties, many merchants found it cheaper to simply bribe the British customs officials into turning a blind eye when smuggled shipments of molasses came in from the French and Dutch West Indies.

At the time, molasses was an important commodity in the American colonies, particularly in the New England colonies of Massachusetts, Rhode Island, Connecticut, and New Hampshire. The result of harvesting sugar cane and boiling it into a dark, thick syrup, molasses was purchased from Caribbean plantations by American merchants. Large quantities would then be sold to New English distilleries, where the molasses would be used to make rum. This rum would then be shipped off to Europe and to Africa; in the latter destination, the rum would often be exchanged for slaves, thereby facilitating the infamous triangular trade. In short, molasses was important to the colonial economy. Since the British West Indies did not produce enough of it to satisfy the demand, merchants were forced to turn to Dutch and French plantations, and, ultimately, to resort to smuggling to avoid the tax.

To make his new version of the molasses tax more acceptable to the colonists, Grenville halved the tax that would be imposed on foreign molasses from 6 pence to only 3 pence per gallon. This would produce an estimated annual revenue of £78,000, which would greatly help with the maintenance of the British army in America. But Grenville had to ensure that these taxes would actually be collected and decided to crack down on corruption amongst British customs officials. At this time, many tax collectors who were supposed to be on duty in the colonies were actually living in England, relying on their deputies to collect bribes from colonial merchants. To put an end to this practice, Grenville issued an ultimatum: all customs officers were to return to their posts in the colonies or resign their office. Many chose resignation, leaving Grenville to fill their posts with more reliable men.

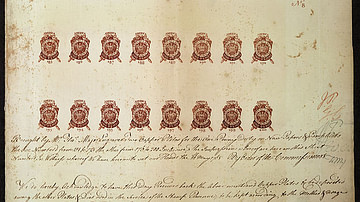

After whipping Britain's tax collectors into shape, Grenville set about presenting his new Sugar Act to Parliament. It passed with barely any opposition and became law on 5 April 1764. Alongside reducing the tax on non-British molasses to 3 pence per gallon, the Sugar Act also mandated that certain goods could only be shipped to Britain from the colonies, and nowhere else; this included lumber, one of the most valuable colonial exports, as well as iron and whalebone. American merchants and ship captains were now required to keep detailed lists of ship cargo, and these papers had to be verified before anything could be unloaded from their ships. If a captain was caught smuggling illicit goods, customs officials were authorized to try him by vice-admiralty courts rather than by jury in local colonial courts. This was because colonial judges and juries tended to be sympathetic to smugglers, while vice-admiralty courts did not use juries and were overseen by a royal appointee. Once convicted, the offenders were obligated to pay substantial fines.

Colonial Reaction

The Sugar Act went into effect at one of the worst possible times. The end of the French and Indian War had led to an economic depression in the colonies, partially because American businesses were no longer being patronized by the British military to procure war supplies. Since the passage of the Sugar Act coincided with the start of these financial troubles, many colonists erroneously blamed the depression on Grenville and the Sugar Act. Colonial merchants were also frustrated when they discovered that Grenville's new class of customs officials were more resistant to bribes than the old ones had been. Outrage over the Sugar Act quickly took hold amongst the colonial merchant class.

Although the merchants found it more difficult to bribe Grenville's tax collectors, this by no means put an end to molasses smuggling. Historian Robert Middlekauff offers the example of merchants from Providence, Rhode Island, who had their contraband molasses loaded into small boats and rowed to designated inlets near the city in the dead of night. Falsified ship's cargo papers could also be procured, for a hefty price. But these smuggling tactics were risky. Oftentimes, smugglers had to be wary of informants, who would alert customs officials to these illegal practices for a reward. Such informants who were found out were not treated kindly by their fellow colonists; one informant, George Spencer, was arrested on the orders of a New York City judge ostensibly for failing to pay his debts. He was then paraded through the city streets and pelted with mud from jeering crowds before being jailed. He was released only after promising to leave the city and never return (Middlekauff, 68). Examples like this illustrate just how seriously the colonial merchants felt about the molasses trade and how far they were willing to go to procure it at the lowest price.

The most radical protests against British authority occurred in Rhode Island, one of the colonies most dependent on the molasses trade. In December 1764, the British Navy had detained a colonial ship suspected of smuggling molasses. During the heated argument that followed, an American crewman attacked the British naval lieutenant with a broadaxe, leading to a brawl; several men were thrown overboard, and one American sailor was run through by the lieutenant's sword. A more dramatic affair took place when an argument over molasses smuggling caused colonial officials to order cannons to fire on a Royal Navy schooner, St. John, as it sailed out of the Newport harbor. While violent fights between American and British sailors had broken out before, the St. John affair was rather unprecedented.

Another incident involved John Robinson, the customs collector of Newport, Rhode Island. After refusing a bribe from the Rhode Island merchants, Robinson found himself treated with disdain by the local courts. Whenever Robinson arrested a smuggler, the colonial judge would wait until Robinson was out of town before trying the case; since Robinson was absent, the accused would be released due to lack of evidence. Matters came to a head in 1765 when a Rhode Island sheriff went so far as to arrest Robinson for alleged damages done to a merchant sloop that Robinson had seized on suspicion of carrying molasses. Robinson languished in jail for two days, during which time he was mocked by local mobs.

Of course, these incidents were outliers, and many merchants resorted to more subtle means of protest, such as hiring sailors that the British Navy hoped to recruit or making sure no pilots were on hand when Royal Navy vessels entered port (Middlekauff, 70). Although these acts of protest were small-scale, and scenes of outright violence rare, they foreshadowed the much larger forms of protest that would break out in the colonies in the following years.

The Issue of Taxation & Representation

As most colonial merchants protested the Sugar Act only so far as it affected their coin purses, some other prominent colonists caught a glimpse of the larger picture and saw a more foreboding image. In Great Britain, the institution of Parliament had been formed around the idea that the people would tax themselves through representatives; taxation was, therefore, a gift given by the people to the government. However, the American colonies had no such representatives in Parliament; why, then, should a tax be forced upon them?

This question was put forth by several prominent American figures such as James Otis, Jr. (1725-1783) of Boston, who argued in a 1764 pamphlet that anyone who took property without consent was depriving the individual of liberty: "If a shilling in the pound may be taken from me against my will, why may not twenty shillings? And if so, why not my liberty or my life?" (Schiff, 74). Otis' protégé, Samuel Adams (1722-1803), echoed this sentiment, asking that if Parliament began taxing American trade, surely it would soon begin taxing American lands. In May 1764, Adams inquired that, if the colonies were taxed without representation, were the colonists not then reduced from "the character of free subjects to the miserable state of tributary slaves?" (Schiff, 73). These sentiments initially put forth by Otis and Adams, such as taxation without representation and the idea of being enslaved to Parliament, would become recurring themes as the colonies hurtled toward revolution.

For now, however, revolution and independence were the furthest thing from anyone's minds; in fact, in 1764, the ideas were unthinkable to even the most outraged colonial merchant. What was immediately important was the repealing of the Sugar Act, which several groups of colonial merchants petitioned Parliament to do. The Governor of Rhode Island, himself a merchant, drafted a remonstrance against the new molasses duties while merchants in New York City and Boston agreed to boycott luxury goods manufactured in Britain. By the winter of 1765, the legislatures of nine out of the thirteen colonies had sent official protests to Parliament; two colonies, New York and North Carolina, had gone so far as to forcefully deny the right of Parliament to impose a tax on the American colonies at all.

While the Sugar Act was vehemently protested by wealthier Americans, such as merchants and government officials, the level of overall protest generally remained low, and was mostly confined to New England and some of the Middle Colonies. Violence, as was previously noted, did occur but only on a sporadic basis. However, the passage of the Stamp Act in 1765 would lead to higher levels of protest across the thirteen colonies.

Conclusion

Grenville's Sugar Act remained in force for two years until it was repealed and replaced by the Revenue Act of 1766. This reduced the tax on molasses even further, to only one penny per gallon for both British and foreign molasses, which effectively ended the issue of molasses smuggling, since it was now cheaper for colonial merchants to simply pay the tax. However, by this point, the genie was out of the bottle; the passage of the Stamp Act in 1765 had built upon the grievances the colonists had expressed over the Sugar Act. The call for 'no taxation without representation' became one of the building blocks of the American Revolution; the Sugar Act of 1764 was, therefore, one of the first direct sparks that would ultimately lead to the independence of the United States of America.