Sun Tzu (l. c. 500 BCE) was a Chinese military strategist and general best known as the author of the work The Art of War, a treatise on military strategy (also known as The Thirteen Chapters). He was associated (formally or as an inspiration) with The School of the Military, one of the philosophical systems of the Hundred Schools of Thought of the Spring and Autumn Period (c. 772-476 BCE), which advocated military preparedness in maintaining peace and social order.

Whether an individual by the name of Sun-Tzu existed at all has been disputed in the same way scholars and historians debate the existence of his supposed contemporary Lao-Tzu (l. c. 500 BCE), the Taoist philosopher. The existence of The Art of War, however, and its profound influence since publication clearly proves that someone existed to produce said work, and tradition holds that the work was written by one Sun-Tzu.

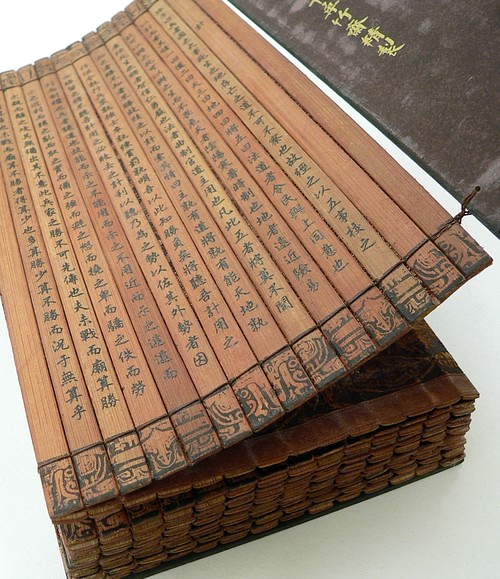

His historicity would seem to have been confirmed by the discovery in 1972 CE of his work, as well as that of his apparent descendant, Sun Bin (d. 316 BCE) who wrote another Art of War, in a tomb in Linyi (Shandong province). Scholars who challenge his historicity, however, still claim that this proves nothing as the earlier Art of War could still have been composed by someone other than Sun-Tzu.

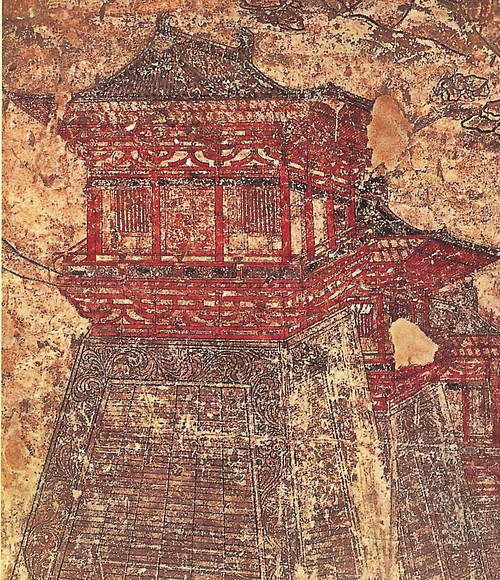

Sun-Tzu is said to have lived, fought, and composed his work during the Spring and Autumn Period which preceded the Warring States Period (c. 481-221 BCE) during which the Zhou Dynasty (1046-256 BCE) was declining and the states once bound to it fought each other for supremacy and control of China.

In the early part of the Spring and Autumn Period, Chinese warfare followed traditional protocol in chivalric behavior before, during, and after an engagement. As the era wore on, however, this adherence to tradition became increasingly frustrating in that no state could gain an advantage over another because each was following exactly the same protocol and employing the same tactics.

Sun-Tzu's work sought to break this stalemate by outlining a clear strategy of winning decisively by whatever means were necessary. His concepts may have been derived from earlier philosophies or may have been based on his own experience in battle. Either way, his theories were put into practice by the king of the state of Qin, Ying Sheng (l. 259-210 BCE) who, by following Sun-Tzu's philosophy, conquered the other states through a policy of total war and established the Qin Dynasty (221-206 BCE), declaring himself Shi Huangdi (r. 221-210 BCE), the first emperor of China. Sun-Tzu's work has been consulted by military figures and business strategists since this time and, in the present day, its lessons on how to achieve one's goals continue to be valued by people of all social classes and occupations.

Historicity of Sun-Tzu

The difficulty in determining whether Sun-Tzu existed is due to the time in which he is supposed to have lived and written his work. The Spring and Autumn Period and later Warring States Period were a chaotic era defined by the decline of the authority of the Zhou Dynasty and the incessant conflict between the states which once supported and defended it.

The turmoil of this era, and the later destruction of various works by the Qin Dynasty, resulted in the loss of many significant records. It seems, however, that some general at least approximating Sun-Tzu's reputation must have lived and served during this time and advocated a policy of total war in order to end the conflict of the warring states and establish peace.

To Sun-Tzu, war was an extension of politics and should be pursued in the interests of the greater good for all, the conqueror and the conquered. In order for warfare to be defined as anything other than a waste of life and resources, however, one needed to win. The scholar Samuel B. Griffith writes:

War, an integral part of the power politics of the age, had become 'a matter of vital importance to the state, the province of life and death, the road to survival or ruin'. To be waged successfully, it required a coherent strategic and tactical theory and a practical doctrine governing intelligence, planning, command, operational, and administrative procedures. The author of 'The Thirteen Chapters' was the first man to provide such a theory and such a doctrine. (Griffith, 44)

Who that man was, though, continues to be debated. Sun-Tzu's historicity is supported by two central works, The Spring and Autumn Annals (the state records of the Zhou Dynasty from 722-481 BCE) and the Records of the Grand Historian (c. 94 BCE) by the Han Dynasty historian Sima Qian (l. 145/135-86 BCE). Scholars have criticized both works for inaccuracies and possible conflations of events. The argument against Sun-Tzu's historicity claims that, had such a great military mind existed, more would have been written of him than just passing references. Still, there are many entries in both works, accepted as historically accurate, which are given the same brief treatment. The scholar Robert Eno comments:

The Spring and Autumn Annals… is brief, not very informative, and inconsistent in its choice of events to note. A typical entry might read, 'Autumn; eighth month; locusts.' (1)

Following Eno's observation, critics of Sun-Tzu's historicity may have a valid point, but it must be conceded that the Annals they claim should have fuller accounts of his life do not have full accounts of any significant figure or event. In the case of the Records, Sima Qian devotes more time to biographies of those whom he felt had been misjudged by history and therefore does not spend a great amount of time on Sun-Tzu who, presumably, would have been well-known to the audience of his day and whose reputation was secure.

Aside from the brief mention, the Records of the Grand Historian has been criticized as unreliable in establishing Sun-Tzu's historicity by scholars claiming it is largely fanciful concerning the descriptions of the Xia and Shang dynasties. This claim might have once been considered valid but archaeological excavations of the 20th century CE uncovered physical evidence supporting Sima Qian's claims completely regarding the Shang and probably in regard to the Xia. The Records, in fact, is for the most part quite accurate, and this would include the section on Sun-Tzu.

The name he is known by, however, is another obstacle in that it is not a personal name; it is a title translated as The Master. As The Art of War repeatedly uses the phrase, “Sun-Tzu said…” in introducing the precepts, it has been argued that some great military genius, name unknown, inspired the work which was written to record his strategies. It has also been suggested that some student of The School of the Military could have written the work to record their central vision that victory in war ensured peace.

Historicity & Influence

Scholars who maintain the historicity of Sun-Tzu point to his role in the victory at the Battle of Boju (506 BCE) as proof. The sources on Sun-Tzu claim that he served King Ho-Lu of Wu (also given as Helu, r. 515-496 BCE) in the Wu-Chu Wars of 512-506 BCE. Ho-Lu wanted to test Sun-Tzu's skill and commitment before appointing him to lead and so commanded him to train his 180 concubines to be soldiers. Sun-Tzu divided the harem into two companies, each with the king's two favorites as their commanders. When he gave the first order to face right, the women laughed, not taking the exercise seriously. Sun-Tzu repeated his command and, again, they giggled; he then had the two 'commanders' executed and replaced. Afterwards, the women obeyed his commands without hesitation and Ho-Lu hired Sun-Tzu as his general.

This story has been considered fiction since at least the 11th century CE when the Sung Dynasty scholar Yeh Cheng-Tse first questioned Sun-Tzu's existence but that has not stopped it from being repeated as fact up to the present day. Even if it never happened, it illustrates Sun-Tzu's commitment to winning, no matter the cost, starting with the discipline of the troops.

According to Sima Qian, the story should be accepted as it is in keeping with Sun-Tzu's concept of discipline as evidenced by the Wu victory at Boju. The Boju victory owed as much to the discipline of the troops as the strategy employed. Sun-Tzu is said to have led the Wu forces with King Ho-Lu, along with Ho-Lu's brother Fugai, and defeated the Chu forces through use of his tactics. The Art of War describes the optimal strategy:

Though according to my estimate, the soldiers of Chu exceed our own in number, that shall advantage them nothing in the matter of victory. I say then that victory can be achieved. Though the enemy be stronger in numbers, we may prevent him from fighting. Scheme so as to discover his plans and the likelihood of their success. Rouse him and learn the principle of his activity or inactivity. Force him to reveal himself, so as to find out his vulnerable spots. Carefully compare the opposing army with your own, so that you may know where strength is superabundant and where it is deficient. In making tactical dispositions, the highest pitch you can attain is to conceal them; conceal your dispositions, and you will be safe from the prying of the subtlest spies, from the machinations of the wisest brains. How victory may be produced for them out of the enemy's own tactics - that is what the multitude cannot comprehend. (6.21-26)

At Boju, the Chu forces were numerically superior to the Wu and King Ho-Lu hesitated to attack, though both armies were martialed on the field. Fugai requested that orders be given to sound the charge, but Ho-Lu refused. Fugai then chose to act on his own in accordance with Sun-Tzu's strategic advice and gave the order to advance. If the troops had not been so well-disciplined, they may have hesitated, waiting on orders from the king. As it was, they obeyed their commander and Fugai drove the enemy from the field. He then pursued them, defeating them repeatedly in five further engagements, and capturing the Chu capital of Ying.

Fugai's success in the Wu-Chu wars was due entirely to his own courage and his belief in the precepts of Sun-Tzu. Through intelligence brought by spies, Fugai knew that the opposing general, Nang Wa, was despised by his troops and that they had no will to fight. Following Sun-Tzu's advice to “force him to reveal himself…find out his vulnerable spots”, he compared his army with that of Nang Wa's and found it sufficient to his ends. He won victory from the enemy's own tactics, as instructed by Sun-Tzu, by refusing to adhere to the standard rules of war as understood at that time. He did not let the enemy retreat to safety and did not allow them to cross the Qingfa River, but instead cut the forces in half mid-stream, prevented their mobilization and formation of lines, and even later attacked them at their dinner.

Total War & Taoist Influence

Fugai's victory at Boju would have been impossible before Sun-Tzu. As noted above, warfare in China in the up through the early years of the Spring and Autumn Period was considered a kind of sport of the noble gentry in which chivalry prevailed and rules were not to be broken; Sun-Tzu changed all of that. Griffith comments:

In ancient China war had been regarded as a knightly contest. As such, it had been governed by a code to which both sides generally adhered. Many illustrations of this are found…For example, in 632 BC the Chin commander, after defeating Ch'u at Ch'eng P'u, gave the vanquished enemy three days' supply of food. This courtesy was later reciprocated by a Ch'u army victorious at Pi. By the time The Art of War was written this code had been long abandoned. (Griffith, 23)

Sun-Tzu changed the rules by applying Taoist principles to warfare and by refusing to consider war a sport. The Art of War states:

In war, then, let your great object be victory, not lengthy campaigns. Thus, it may be known that the leader of armies is the arbiter of the people's fate, the man on whom it depends whether the nation shall be in peace or in peril. (2.19-20)

Sun-Tzu had no patience with the protracted games generals seemed to enjoy playing with each other. Once hostilities had erupted, one's priority was to defeat the enemy, not indulge oneself in chivalry which could only prolong the conflict and cost more lives. Scholar John M. Koller comments on how Taoism influenced the concepts of The Art of War:

Taoism finds [the] way for living well in doing what is natural, rather than in adhering to the conventions of society. Consequently, instead of emphasizing the cultivation of virtue and the development of human relationships as Confucianism does, Taoism emphasizes the spontaneous ease of living attained by acting in accord with the natural way of things. (243)

This “spontaneous ease of living” is exemplified in Sun-Tzu's writings in that he consistently emphasizes the natural path to victory while ignoring the conventional wisdom of the time concerning military engagements. Koller further writes that the great Taoist work, the Tao-Te-Ching, “reflects a horror of war and a deep-felt yearning for peace” (244) and Sun-Tzu's work reflects this also in that the best way to achieve peace is by a swift victory or, better yet, by defeating an enemy before war is even begun.

Sun-Tzu writes, “To fight and conquer in all your battles is not supreme excellence; supreme excellence consists in breaking the enemy's resistance without fighting” (2.2). His foundational strategy, throughout his writings, can be found in the lines from the Tao-Te-Ching:

Yield and overcome

Bend and become straight

Empty and become full. (Verse 22)

By adapting oneself to one's situation, rather than rigidly holding fast to how one thinks things should be, one is able to recognize the fluidity of conditions and act upon them decisively.

Sun-Tzu & the Rise of Dynasties

Although Sun-Tzu's work seems to have been known during the Warring States Period, his precepts were not made use of until the reforms of the Qin statesman Shang Yang (d. 338 BCE) who may have been acquainted with the work. In keeping with Sun-Tzu's vision, Shang advocated total war instead of adherence to chivalric practices of the past. Shang Yang's reforms were implemented fully by the Qin King Ying Zheng who, in conquering the other states between 230-221 BCE, united China under his rule as Shi Huangdi and founded the Qin Dynasty, the first imperial dynasty of China.

Following the collapse of the Qin Dynasty between 206-202 BCE, the leading contenders for rule of China, Liu Bang of Han (l. c. 256-195 BCE) and Xiang Yu of Chu (l. 232-202 BCE), made further use of Sun-Tzu's principles in fighting each other. The strategies leading to the decisive victory of the Han at the Battle of Gaixia (202 BCE) follow the ideology of The Art of War in many respects but, most notably, in the Han general Han Xin (l. 231-196 BCE) relentlessly attacking Xiang-Yu without regard to the former rules of warfare and the singing of the native songs of Chu, by the Han army, to demoralize the Chu forces.

The Battle of Gaixia led to the rise of the Han Dynasty (202 BCE - 220 CE) which revived the earlier culture of the Zhou Dynasty and encouraged cultural developments including the invention of paper, the refinement of gunpowder, written history, and, in 130 BCE, the opening of the Silk Road and the beginning of worldwide trade. The Han Dynasty set the standard model for all those which followed and so it could be argued that The Art of War was the foundational text in establishing the imperial dynasties which would rule China up until 1912 CE.

Conclusion

The Art of War is known to have been consulted by the warlord Cao Cao (l. 155-220 CE), one of the generals who tried to win the throne when the Han Dynasty was in decline. Cao Cao wrote a commentary on the work, establishing its importance at that time, but was no doubt known to the nobles who engaged in the War of the Eight Princes (291-306 CE), each of whom waged war on each other according to Sun-Tzu's precepts. Cao Cao's defeat at the Battle of Red Cliffs (208 CE) resulted in the division of the Three Kingdoms Period (220-280 CE) which established separate kingdoms all led by former generals who had used Sun-Tzu's work.

The Art of War continued to be consulted afterwards throughout China's history and eventually came to be considered one of the classics and required reading. From China, the work traveled around the world and, in the present day, is among the bestselling books of all time. Sun-Tzu's maxim that “All warfare is based on deception” (1.18) has been cited as an essential component of any military campaign as well as in business transactions, legal proceedings, and political campaigns.

His work has grown in popularity through its translations around the world and has been made use of, not only by the military, but by business strategists, political advisors, life coaches, and others who advise people on their financial or personal choices. Whether Sun-Tzu as an individual existed has ceased to have any real importance as the work which bears his name has made that name immortal.