Sword Beach was the easternmost beach of the Allied D-Day Normandy landings of 6 June 1944. The 3rd British Infantry Division was given the task of taking the beach while paratroopers and Royal Marine and French Commando units secured the beach exits and the eastern flank of the Allied invasion.

Operation Overlord

The amphibious assault on the beaches of Normandy was the first stage of Operation Overlord, which sought to free Western Europe from occupation by Nazi Germany. The supreme commander of the Allied invasion force was General Dwight D. Eisenhower (1890-1969) who had been in charge of the Allied operations in the Mediterranean. The commander-in-chief of the Normandy land forces, 39 divisions in all, was the experienced General Bernard Montgomery (1887-1976). Commanding the air element was Air Chief Marshal Trafford Leigh Mallory (1892-1944), with the naval element commanded by Admiral Bertram Ramsay (1883-1945).

Nazi Germany had long prepared for an Allied invasion, but the German high command was unsure where exactly such an invasion would take place. Allied diversionary strategies added to the uncertainty, but the most likely places remained either the Pas de Calais, the closest point to British shores, or Normandy with its wide flat beaches. The Nazi leader Adolf Hitler (1889-1945) attempted to fortify the entire coast from Spain to the Netherlands with a series of bunkers, pillboxes, artillery batteries, and troops, but this Atlantic Wall, as he called it, was far from being complete in the summer of 1944. In addition, the wall was thin since there was no real depth to the defences.

Field Marshal Gerd von Rundstedt (1875-1953), commander-in-chief of the German army in the West, believed it would be impossible to stop an invasion on the coast and so it would be better to hold the bulk of the defensive forces as a mobile reserve to counterattack against enemy beachheads. Field Marshal Erwin Rommel (1891-1944), commander of Army Group B, disagreed and considered it essential to halt any invasion on the beaches themselves. Further, Rommel believed that Allied air superiority meant that movements of reserves would be severely hampered. Hitler agreed with Rommel, and so the defenders were strung out wherever the fortifications were at their weakest. Rommel improved the static defences and added steel anti-tank structures to all the larger beaches. In the end, Rundstedt was given a mobile reserve, but the compromise weakened both plans of defence. The German response would not be helped either by their confused command structure, which meant that Rundstedt could not call on any armour (but Rommel, who reported directly to Hitler, could), and neither commander had any control over the paltry naval and air forces available or the separately controlled coastal batteries. Nevertheless, the defences were bulked up around the weaker defences of Normandy to an impressive 31 infantry divisions plus 10 armoured divisions and 7 reserve infantry divisions. The German army had another 13 divisions in other areas of France. A standard German division had a full strength of 15,000 men.

Operation Neptune

Preparation for Overlord occurred right through April and May of 1944 when the Royal Air Force (RAF) and the United States Air Force (USAAF) relentlessly bombed communications and transportation systems in France as well as coastal defences, airfields, industrial targets, and military installations. In total, over 200,000 missions were conducted to weaken as much as possible the Nazi defences ready for the infantry troops about to be involved in the largest troop movement in history. The French Resistance also played their part in preparing the way by blowing up train lines and communication systems that would ensure the German armed forces could not effectively respond to the invasion.

The Allied fleet of 7,000 vessels of all kinds departed from English south-coast ports such as Falmouth, Plymouth, Poole, Portsmouth, Newhaven, and Harwich. In an operation code-named Neptune, the ships gathered off Portsmouth in a zone called 'Piccadilly Circus' after the busy London road junction and then made their way to Normandy and the assault areas. At the same time, gliders and planes flew to the Cherbourg peninsula in the west and to Ouistreham on the eastern edge of the planned landing. Paratroopers of the 82nd and 101st US Airborne Division attacked in the west to try and cut off Cherbourg. At the eastern extremity of the operation, paratroopers of the 6th British Airborne Division aimed to secure Pegasus Bridge over the Caen Canal. Other tasks of the paratrooper and glider units were to destroy bridges to impede the enemy, hold others necessary for the invasion to progress, destroy gun emplacements, secure the beach exits, and protect the invasion's flanks.

Attacking Sword: Airborne Troops

The amphibious attack was set for dawn on 5 June, daylight being a requirement for the necessary air and naval support. Bad weather led to a postponement of 24 hours. Shortly after midnight, the first waves of 23,000 British and American paratroopers landed in France. From 3:00 a.m., air and naval bombardment of the Normandy coast began, letting up just 15 minutes before the first infantry troops landed on the beaches at 6:30 a.m. The area was divided into five beaches, each with its own code name. While US troops attacked Utah Beach and Omaha Beach to the west, Canadian troops landed at Juno Beach, and British troops launched an assault on Gold beach and, at the eastern end of the front, on Sword Beach, located between St-Aubin-sur-Mer and the River Orne. Sword Beach, which was 8 miles (12.8 km) long, was further divided into four sectors (west to east): Oboe, Peter, Queen, and Roger.

Paratroopers of the British 6th Airborne Division were tasked with securing the east flank of the invasion area, destroying vital bridges across the Dives River to impede German troop movements, capturing intact bridges over the Orne Canal and Orne River, and knocking out the heavy guns of the Merville battery on the Orne estuary. The four guns at Merville, which were well protected against aerial bombardment, each having their own concrete casement, could fire upon the beach and the Allied fleet off the coast. The defenders had deliberately flooded the area to impede such an attack, and the guns themselves were surrounded by a formidable array of mines, 20 machine-gun nests, a trench system, and rolls of barbed wire. RAF Lancaster bombers attacked the area shortly before the paratroopers were dropped in but failed to destroy the Merville battery.

The paratroopers faced immediate problems. Heavy flak meant their aircraft were obliged to take evasive action, and the men were dropped over a much wider area than planned. The pathfinders also suffered equipment failures. Many men, weighed down by equipment, drowned in the watery marshland. Much essential equipment like mortars and mine detectors was also lost. Only 160 men out of 600 made it to the operation's meeting area, but the mission had to carry on regardless. The guns were charged, taken and destroyed, but at the cost of 75 casualties in a ferocious attack that lasted 20 minutes. As it turned out, the guns were much smaller than anticipated and could not have fired upon Sword anyway. Such are the fortunes of war. Other battalions knocked out the bridges as planned while gliders brought in more men by the hour. The British airborne troops overcame significant obstacles and took their objectives on schedule. It now remained for these lightly armed troops to hold on to the bridges until the Commandos landing on the beach could reach and relieve them.

The Amphibious Assault

Naval ships, including the battleships HMS Ramillies and Warspite, bombarded the coast before landing craft carrying the tanks went in around 7:30 a.m. The invasion fleet was in the range of the mighty 155-mm (6 in) guns of Le Havre. The Allied warships had their own big guns, and these were used to bombard the defences and the Le Havre guns. Fortunately for the Allies, the Le Havre guns concentrated on firing at HMS Warspite instead of Sword Beach, which was, in any case, so filled with smoke the German gunners could not find their range.

The tide was unusually high that morning, and this made the beach very narrow, no more than 15 yards (13.7 m) in places. The defenders had also sunk obstacles in the shallows and littered the beach with anti-tank obstacles. As Corporal John Barnes, a tank commander, noted:

There's spray in your face. You're watching everything that's happening, you're seeing explosions, there's smoke screens being put up…Desperately in your mind is, 'I must get to the beach, I must get to the beach'. You know that if you don't get there, you're going to sink in the water…Then you think, 'What's that black thing there?' and you're looking very hard because it's rough weather and you're wondering whether it's an obstacle that has a mine on.

(Bailey, 195-6)

34 of the first 40 Sherman DD tanks made it onto the beach and headed for their preassigned exit points and to attack gun emplacements. Sherman and Churchill tanks with well-trained crews attacked the pillboxes while Crab flail tanks cleared mines to create safe lanes on the beach. Three rows of mined obstacles along the entire beach claimed many of the tanks before sheer numbers cleared the way. Royal Marine divers worked in the shallows to clear the underwater obstacles, which could (and sometimes did) rip out the bottom of a landing craft and sink it in seconds. Special vehicles dropped logs to fill the anti-tank ditches, and bulldozers flattened the barbed wire.

The shallow-bottomed LSIs (Landing Ships, Infantry) went in next (in many cases actually overtaking the tanks in the water) and disgorged troops of the 3rd British Infantry Division, 1st British Corps (2nd British Army) on the beach. Their commander was Major General Tom Rennie. The men had to survive the heaving water, mines, and enemy fire from machine guns and mortars. Smoke bombs were fired to obscure the beach, and the men waded through the last 300 yards (275 metres) to reach the shore. Wrecked tanks and armoured vehicles became valuable points of relief for the infantry units swarming up the beach but also impeded the landing of other vehicles. Sergeant Arthur Thompson recalls his landing:

As soon as the craft hit the beach, the front drops and the centre group have to dash out straight away, otherwise the others can't get out. And this young Joe we had with us, he stood there and he was petrified, so nobody could move. Everybody is just shouting, 'Get out the bloody road!'…By that time the beach was getting covered with dead and wounded, you were jumping over them as you went in.

(Bailey, 200-1)

The 1st Special Service Brigade of commandos, led by Brigadier Lord Lovat, landed near Colleville with the task of relieving the paratroopers holding two vital bridges, including the Pegasus Bridge at Bénouville, which meant the German 21 Panzer Division could not cross into the landing area and the Allies had a route into more open country. The presence of the 21 Panzer Division so close to Caen and the delays in landing meant that city could not be captured on D-Day as rather optimistically planned. It would take two months of hard fighting to take Caen.

Back on the beach, the German pillboxes were proving a tough nut to crack, as described by the Commando, Corporal Jim Spearman:

Domineering the whole place were these tremendous big pillboxes. No matter where you went, you couldn't get out of range of them; they covered the beach very well. The fortifications were excellent. if you think of a pillbox, you can go up to it, go to a slit and drop a grenade in, but these bloody defences they had on the beach there had about dozen slits in them. They were tremendous things.

(Bailey, 212)

As the beach came increasingly under Allied control, more troops piled in and attacked sites where the German forces had dug in such as the heavy guns at the casino of Riva Bella just west of Ouistreham where there was still heavy fighting. German sniper fire was a constant menace, as was mortar and artillery fire from batteries deeper inland. The defenders kept control of Lion sur Mer, holding up the attackers and preventing an immediate link-up with the forces landing on Juno Beach.

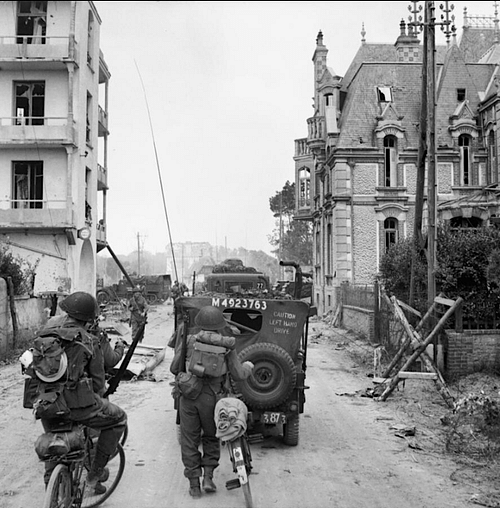

Troops landed at Sword were amongst the most cosmopolitan of the Normandy landings and included French, Dutch, Poles, Norwegians, and Belgians, as well as a number of German Jewish refugees. All of these troops were marshalled by the beachmaster, who urged men to push on and not linger on the beach. The soldiers were welcomed as they passed through by the mayor of Colleville, who was wearing a brass fireman's helmet, and a young Frenchwoman wearing a Red Cross armband who tended the wounded. Other picturesque scenes amongst the chaos of war were British troops halting to brew cups of tea, French soldiers pausing to pick strawberries, and a French farmer busy pasting posters onto doorways which read "Vive les Tommies!" and "Vive la France!". By 11:00 a.m., Allied troops were pushing on beyond the beachhead helped by the German command's indecision to deploy panzer divisions like the SS Hitler Jugend and the effectiveness of the Allied air support when the German tanks did finally mobilise. By 13:00, the commandos had linked up with the airborne troops at Pegasus Bridge. Gradually, the German forces were recovering from the initial shock and by mid-afternoon they were launching counterattacks, but it was too little too late, as Allied troops kept pouring onto the beach. The Sword beachhead had been definitively established.

On D-Day, 28,845 troops were landed at Sword with 630 casualties (although no official figures exist for D-Day alone and estimates can vary). The next day, the troops on Sword Beach linked with the Canadian force on Juno Beach.

The Battle for Normandy

By the end of D-day, 135,000 men had been landed and relatively few casualties were sustained – some 5,000 men. The defenders eventually organised themselves into a counterattack, deploying their reserves and pulling in troops from other parts of France. This is when French resistance and Allied aerial bombing became crucial, seriously hampering the German commanders' efforts to reinforce the coastal areas of Normandy. Most of the German generals wanted to withdraw, regroup, and then reattack in force, but, on 11 June, Hitler ordered there be no retreat. Operation Neptune officially ended on 30 June. Around 850,000 men, 148,800 vehicles, and 570,000 tons of stores and equipment had been landed since D-Day. The next phase of Overlord was to push the German army out of Normandy, but this proved more difficult than anticipated with the defenders fighting resolutely and aided by the broken bocage countryside of fields and hedgerows. There were some serious Allied setbacks such as the staunch defence of Caen and very heavy fighting around Avranches. It was not until August that General Patton and the US Third Army were punching south at the western side of the offensive. The Brittany ports of St. Malo, Brest, and Lorient were taken, and the Allies swept southwards to the Loire River from St Nazaire to Orléans. On 15 August, a major landing took place on the southern coast of France, the French Riviera Landings. On 25 August, Paris was liberated. The northern and southern Allied armies linked up in September and pushed the German army back towards Germany as the Second World War reached its final phase.