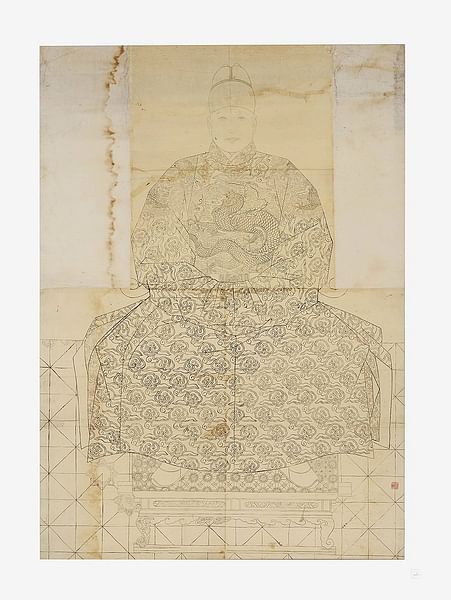

King Taejong of Joseon (r. 1400-1418) was the third ruler of the Joseon Dynasty in Korea. Taejong was a driving force behind consolidating and strengthening the king’s power, and while he was an effective ruler, his violent means of winning and keeping power set a dangerous precedent in the politics of the Early Joseon Period.

Role in the Founding of Joseon

Taejong was born on 13 June 1367 as Yi Bang-won to Yi Seong-gye (1335-1408), the future King Taejo of Joseon (1392-1398), and his wife Han Sinui (1337-1391). Bang-won was the fifth son of Seong-gye and Sinui. He also had one younger brother, and two younger half-brothers born from his father’s second wife, Sindeok (1356-1396).

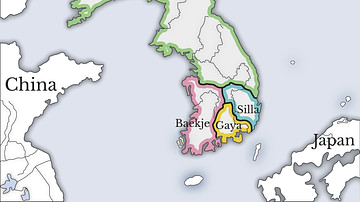

In 1388, Yi Seong-gye planned and carried out a coup to overthrow the Goryeo Dynasty (918-1392). Seong-gye, a general, was tasked with invading the Liaodong region of China by King U of Goryeo (r. 1374-1388). When he reached Wihwado Island at the border of Liaodong and Korea on the Yalu river, Seong-gye turned his army back to begin his coup. Seong-gye involved Bang-won in much of his planning of the coup, and Bang-won helped his father carry out the coup which created the Joseon Dynasty (1392-1897).

While the coup itself involved little bloodshed, Bang-won was behind most of the plots to consolidate and legitimize Seong-gye’s power, and he killed many of Seong-gye’s opposition in the subsequent years—against his father’s wishes. The most prominent victim of Bang-won was Jeong Mong-ju (1338-1392). Jeong was an influential politician and scholar-official at the end of the Goryeo Dynasty and one of the biggest opponents of Seong-gye’s rule. While Seong-gye wanted to keep him alive and work on changing his opinion, which would change the opinion of his followers, Bang-won had other ideas and killed him after a party thrown in his honor.

Before killing Jeong, Bang-won crafted a sijo, a particular Korean poem, as a final attempt to turn his loyalty from Goryeo to Joseon. The poem was as follows:

So, what if we did this, what if we did that.

So, what if the vines of the Mansu Mountain (ten thousand year Mountain) are bounded together.

We will likewise enjoy our lives for the next hundred prosperous years together. (Roh, 18)

To which Jeong Mong-ju replied with a sijo of his own:

My body may die again and again for a hundred times again.

My body may turn into a pile of bones and becomes dust.

My one and only mind toward you [previous king] will not vanish. (Roh, 18)

Jeong Mong-ju’s assassination was one of the last pieces put in place before confirming Seong-gye as King Taejo (r. 1392-1398).

First Strife of Princes

After assuming the throne, King Taejo named his youngest son, Bang-seok (1382-1398), as his heir. Bang-won was mad at his father for naming Bang-seok heir instead of him, as Bang-won was the son who most helped his father win the crown. All of Taejo’s sons had private armies, so in 1389, Bang-won used his army to kill both his half-brothers Bang-seok and Bang-beon (1381-1398). Bang-won also killed two of his father’s advisors during this conflict, Jeong Do-jeon (1342-1398) and Nam Eun (1354-1398). Jeong and Bang-won held vastly different views on how the new dynasty should be run. Jeong believed minister-scholars should run Joseon, while Bang-won thought the king should rule as an absolute monarch. To make matters worse, both Jeong and Nam supported Bang-seok being named heir over Bang-won.

In the aftermath of this conflict, Bang-won persuaded Taejo to name his oldest surviving son, Bang-gwa (1357-1419), as heir in a move to show his goal was not to win the throne himself. Mourning his sons and wife—who suddenly died earlier—Taejo abdicated, with Bang-gwa becoming King Jeongjong (r. 1399-1400). Jeongjong quickly moved the capital of Joseon from Seoul to Kaesong, the city he preferred to live in.

Second Strife of Princes & Rise to the Throne

Even though Jeongjong was king in name, Bang-won pulled the strings behind the scenes, with no royal orders occurring without his blessing—much like his father, Yi Seong-gye, did to the final Goryeo king Gongyangan (r. 1389-1392). One order Bang-won had Jeongjeon put in place was a ban on all private armies. Even though Bang-won had recently killed the crown prince with a private army, Bang-won wanted all armies disbanded to ensure nobody could challenge Jeongjong - which would challenge Bang-won’s power.

After Jeong Do-jeon and Nam Eun were killed, Bang-won’s older brother Bang-gan (1364-1421) became his primary rival to the throne. Bang-won and Bang-gan both grew personal armies in secret - as they were now illegal - before Bang-gan launched an attack on Bang-won in 1400. This became known as the Second Strife of Princes. Bang-won was able to defeat his brother’s army, and instead of killing Bang-gan, Bang-won exiled him but killed the advisors who helped urge his brother to build an army and attack Bang-won.

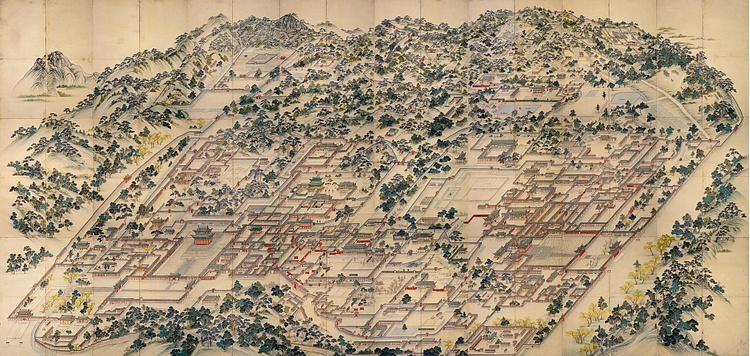

After killing yet another of his brothers, Jeongjong - who was intimidated by Bang-won even before the Second Strife of Princes - named Bang-won his heir and then abdicated. Bang-won was crowned as King Taejong (r. 1400-1418) and moved the capital back to Seoul from Kaesong, the city his father initially established as Joseon's capital. After seeing his son kill so many people close to him to win the throne, the former King Taejo left the capital to live out his days in his birthplace of Hamheung.

Early Reign & Consolidation of Power

Taejong spent much of his reign expanding and consolidating the throne’s power. In the first years of his reign, he exiled and killed his wife’s brothers so that they could not challenge for the throne or be a poor influence on her. One of Taejong’s first orders as king was to reorganize the Uijeongbu (State Council of Joseon). The new Uijeongbu was the highest organ of government, and comprised seven members dedicated to advising and carrying out the king’s orders to lower-level government organs. The Uijeongbu’s power was limited compared to the Topyeongeuisasa (Supreme Council), Goryeo’s comparative government organ. All decisions made by the Uijeongbu had to have the blessing of the king, which expanded the power of the throne.

Under the Uijeongbu were many layers of regional and local government. Each level of government had to run decisions by their supervisor, so the king had ultimate authority in all matters of running the country - which was Bang-won’s philosophy and the reason he killed Jeong Do-jeon and Nam Eun in the First Strife of Princes.

Taejong, in his reorganization of government to make it more efficient, divided Korea into eight provinces, with each province divided into counties. The land was, overall, divided into 350 counties. Each province and county had government officials stationed in them to ensure the smooth running of regional and local government. This was a change from Goryeo policy, where there were many divisions of land that had no government officials. This was another way Taejong consolidated the throne’s power.

Improvements to Life in Korea

Even though Taejong was ruthless, cunning, and violent to win the throne, he was an effective ruler and made several changes to policy that improved the lives of Koreans. One policy was the Sangso, or a way of sending one’s opinions to the throne itself. Any official of the country could send a Sangso from their local government office to the king himself. The king was able to read these to hear the views of his subjects. This was unique and unheard of at the time.

Another policy, which could have harmed some individuals but overall created a better environment for the public, was creating identification cards after a 1413 census of almost 5 million people. These Hopae tablets were required by all males over 16 and included birth dates, places of birth, and other information. This ensured peasant farmers stayed farming their fields instead of abandoning them in tough times, allowing Joseon to better use their farmland. These cards also ensured no men could skip their mandatory military service. Mandatory service was even more important in Taejong’s reign than ever before, as he increased the size and strength of the military when he banned personal armies.

Taejong also freed hundreds of thousands of slaves - almost one-third of the Early Joseon population -during his reign, many of whom were born as commoners but were forced into slavery during the Goryeo period to pay off debt or to provide necessities for their family. Taejong allowed these former slaves to become artisans or manufacturers, supporting themselves and earning wealth with the requirement of paying a tax.

Finally, Taejong loosened the rigid social classes of Goryeo and allowed for upward mobility, even if it was still difficult to move between classes. As Jinwung Kim noted, "in this early period upward mobility, although a singular phenomenon, was not impossible. Nevertheless, Joseon was certainly a hierarchical society" (202).

Laying the Groundwork for King Sejong & Abdication

Through the changes to the throne’s power, government organization, and social structure, Taejong was able to lay the groundwork for his third son, who would become King Sejong the Great (r. 1418-1450) to enact policies which greatly enhanced Joseon and its people. Taejong, much like he did earlier in his life, plotted to have his third son become king without bypassing the traditions of naming his first-born son heir.

Taejong finally named Sejong his heir in 1418 and abdicated shortly afterwards. Taejong’s power, however, did not end. Taejong ruled through Sejong as a puppet-king, similar to how he ruled through his brother Jeongjeon almost 20 years prior. Further, he once again planned and carried out an assault on political opponents by killing all government members who opposed that Taejong named Sejong his heir. Taejong also killed Sejong’s father-in-law and two of his wife’s uncles in order to cement Sejong’s power. Taejong finally loosened his grip on power in the final year of his life and died on 30 May 1422.

Legacy

King Taejong was and still is a very controversial figure in Korean history. While he was a good ruler who improved the lives of his subjects and laid the groundwork for one of Korea’s greatest historical figures, he also planned and carried out many brutal assaults on both family members and government officials alike.

His penchant for violence in order to gain, hold, and strengthen power "set a precedent of bloody purges among royalty and the bureaucracy that continued throughout the Joseon dynasty and greatly contributed to the weakening of the kingdom" (Jinwung Kim, 189). These events still overshadow his policy decisions today.