Taifas ("factions" or "camps") were small independent Muslim kingdoms and principalities that emerged after the fall of hegemonic Muslim caliphates in al-Andalus – the Muslim-controlled part of the Iberian peninsula – during the High Middle Ages. There were three taifa periods between 1031 and the mid-13th century.

The Three Taifa Periods

The first taifa system started after the Umayyad Caliphate of Cordoba fragmented in 1031. The Umayyads' decline began in earnest in 1008 and had been marked with domestic unrest, disputes over hereditary succession, and Berber incursions. In the disruption – or fitna – that accompanied the Umayyad collapse, warlords and adventurers from throughout al-Andalus staked out their territory. These fiefdoms became taifas, and between 30 and 50 were established at this time. The number of taifas drastically shrunk in the ensuing scramble. Some were only minor city-states that quickly merged into larger polities or were conquered by their neighbors. Eventually the taifas coalesced around Zaragoza, Valencia, Toledo, Badajoz, Seville, and Granada. Cordoba, which once boasted a population of 500,000 and had served as the center of Umayyad power and prestige, never regained its former stature.

After Spanish Christians under Alfonso VI, king of Castile and León (r. 1072–1109), conquered the taifa of Toledo in 1085, the other taifas petitioned Yusuf ibn Tashfin of the Almoravid Dynasty in the Maghreb for military support. The Almoravids arrived and promptly drove the Castilians back. At that point, the would-be rescuers decided to stay as the new masters of Al-Andalus, and they absorbed the taifas by 1090.

The Almoravid reign was not to last. The second taifa system gradually emerged in 1144 as another Berber dynasty – the Almohads – entered al-Andalus and unseated the Almoravids. This new Berber dynasty conquered most of the taifas by 1172. The Almohads dominated al-Andalus for the next 40 years until a decisive Christian victory at Las Navas de Tolosa in 1212 permanently broke Almohad military power and the caliphate fragmented once again for the third and final taifa period. Except for Granada, most of the remaining taifas were absorbed into Castile or Aragon by the mid-13th century.

Warfare

Conflict in the Iberian Peninsula closely resembled feudal conflict elsewhere in Christian Europe or in Japan during the Sengoku period. Diplomacy between taifas was characterized by mercurial and fluid alliances. Religion was not the greatest indicator of allegiance. These military and political arrangements included similarly fragmented Christian kingdoms as both Christians and Muslims sought to gain economic and strategic advantages over their rivals. Seeking reputation and wealth, mercenaries and adventures sold their services and fought for Muslim and Christian lords. For example, the legendary Rodrigo Diaz, or El Cid, spent more of his career serving Muslims than fellow Christians. The machinations of the rest of Christian Europe also affected what happened in al-Andalus, as the Second Crusade (1147-1149) proved. In that campaign, crusaders who did not wish to travel to the Holy Land opted for closer and more convenient targets in al-Andalus.

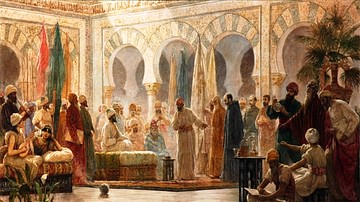

Politics & Culture

At the start of the first taifa period, Andalusian Christians and Jews lived under limited discrimination. There was periodic violence against them, but that did not define the relationship between adherents of the competing faiths. As "People of the Book," Christians and Jews enjoyed legal protection and were respected for the most part so that both religious minorities assimilated into Andalusian society. Many Muslim emirs and princes employed Jews in positions of great influence. Although the taifas were remarkably tolerant for the time and certainly more accommodating than their successors, there was a great deal of strife as various Christian kingdoms sought to drive wedges between Muslims, exacerbate internal quarrels, and weaken them during the Reconquista.

In addition, taifas regularly paid parias, or tributes in the form of money, commodities, or experts to Christian kingdoms in exchange for military aid. It is difficult to separate paria payments from mercenary fees or protection money, as they are somewhat intertwined. Regardless, this was a mutually symbiotic relationship, with culturally dynamic and wealthy but politically weak and unstable taifas receiving support from politically formidable but economically lackluster Christian powers. Paria payments were absolutely vital for Christian kingdoms to survive, as they needed those funds to advance their own domestic projects and maintain their Christian vassals' loyalty. Initially, taifas easily afforded the payments and deducted them from budget surpluses. The payments, however, gradually weakened many taifas because the constant warfare meant Christian reinforcements were always needed and increasingly bold Christian armies threatened to attack if they were not paid. The financial drain facilitated the Christian conquest later. Ironically, the very warriors the paria payments were intended to buy off were the same who ended the taifas.

Taifa rulers patronized the arts and sciences in order to attract poets and scholars from throughout Al-Andalus. It was necessary for Muslim lords to do so because they did not wield much political legitimacy. These leaders were a combination of Arab Umayyad loyalists, Berbers from the Maghreb, and warlords. Their claims to rule were tenuous at best. The lords could not justify their rule through shared bloodlines with Umayyad kings and were frequently beset by internal detractors. They could, however, cement their legitimacy through the arts and sciences.

There was a diaspora of scholars after the fall of the Umayyad Caliphate and so many talented individuals sought employment from reputable patrons. As the Reconquista gained momentum, many scholars including Jews fled from recent Christian conquests to taifas and worked for courts that would have them. Some leaders even dabbled in poetry themselves in an effort to make themselves and their courts more refined. The larger taifas specialized in various disciplines; Seville, Toledo, and Zaragoza focused on poetry, science, and philosophy respectively. The ubiquitous competition between rival taifas, along with the constant migration of itinerant artists from diverse backgrounds, blended local artistic techniques and created a distinct Andalusian style. The specialists' geographic mobility also translated into a great amount of both upward and downward social mobility.

Life under the Almoravids was characterized by increased intolerance and repression, but the taifas still retained their cultural dynamism. Remarkably, even the Almoravids were soon quite taken with the taifas' learning and culture and began to adopt Andalusian techniques and motifs in their own art, adding a bit of life and verve to their perpetually severe styles. The shared Arab and Islamic cultural advances would continue to influence Spain and, eventually, much of Western Europe as well.

Economy

Interregional trade was brisk at the start of the first taifa period, as the Muslim polities were ideally situated to take advantage of commerce with the Berbers in the Maghreb region of North Africa. The Maghreb provided trade hubs for trans-Saharan caravans. As the Almoravid Dynasty took power, it also gave the taifas access to the Ghana Empire in West Africa as well as the Upper Niger along with their gold, slaves, gum, and ivory exports. By extension, taifas gave their Christian partners access to commerce across the breadth of the Islamic and Silk Roads commercial networks. This arrangement resulted in the taifas supplying precious metals, ivory, and silk to the rest of the peninsula. Christian kingdoms, in turn, supplied timber and furs to their Muslim trading partners.

Al-Andalus was much more urbanized than the Christian kingdoms, with some taifas urbanizing more than others. They lived in semi-urban societies while their Christian and Almoravid counterparts were heavily rural. Al-Andalus, in fact, was one of the most urbanized regions of the Islamic world and boasted an impressive level of development and educational attainment. It was not a feudal system but, instead, rested on a system that emphasized local and regional markets. Rural hinterlands provided food and raw materials to cities that functioned as their primary markets. A skilled workforce maintained a complex irrigation system that allowed the taifas to grow luxury crops such as grapes and olives and supply the manufacturing sector. The farmers and peasants maintained that productive system by treating it as a science, and they kept it running despite frequent raids by rival Christian and Muslim armies.

Just as individual taifas specialized in certain fields of knowledge, so to did they specialize in particular industries including sericulture, glassware, and book publishing. The taifas were focused on being self-sufficient first but were keen on exporting when practical.

Despite al-Andalus' robust economy, it stagnated as each taifa's ruler prioritized their own material well-being, lavish courts, and legitimacy over any plan for long-term sustainability. The amount of gold and silver specie also declined as increased paria payments required more coin. Attempts to make up for the shortfall through taxation met with popular discontent and even rebellion. Taifa economies remained strong but increasingly vulnerable, and they were tempting targets for resurgent Christian kingdoms.

The taifa periods were short-lived, but they saw a wave of innovation and intellectual curiosity that made al-Andalus a center of innovation and scholarship. The cosmopolitan mixture of Christians, Jews, and Muslims from throughout al-Andalus, the Maghreb, and the Mediterranean made indelible marks on Spanish cuisine, language, and culture that persist until the present day.