Teotihuacan, located in the Basin of Central Mexico, was the largest, most influential, and most revered city in the history of the New World. It flourished in Mesoamerica's Golden Age, the Classic Period of the first millennium CE. Dominated by two gigantic pyramids and a huge sacred avenue, the city’s architecture, art, and religion would influence all subsequent Mesoamerican cultures.

At its height from 375 and 500 CE, the city controlled a large area of the Mexican central highlands of Mexico and likely exacted tribute from conquered territories. Around 600 CE, the major buildings of the city were destroyed by fire, artworks were smashed and the city went into decline. Teotihuacan remains today the most visited ancient site in Mexico. It is listed by UNESCO as a World Heritage Site.

Historical Overview

In relation to other Mesoamerican cultures Teotihuacan was contemporary with the early Classic Maya (250 - 900 CE) but earlier than the Toltec civilization (900-1150 CE). Located in the valley of the same name, the city first formed between 150 BCE and 200 CE and benefitted from a plentiful supply of spring water which was channelled through irrigation. The largest structures at the site were completed before the 3rd century CE, and the city reached its peak in the 4th century CE with a population as high as 200,000. Teotihuacan is actually the Aztec name for the city, meaning "Place of the Gods"; unfortunately, the original name is yet to be deciphered from surviving name glyphs at the site.

The city's prosperity was in part based on the control of the valuable obsidian deposits at nearby Pachuca, which were used to manufacture vast quantities of spear and dart heads and which were also a basis of trade. Other goods flowing in and out of the city would have included cotton, salt, cacao to make chocolate, exotic feathers, and shells. Irrigation and the natural attributes of local soil and climate resulted in the cultivation of crops such as corn, beans, squash, tomato, amaranth, avocado, prickly pear cactus, and chili peppers. These crops were typically cultivated via the chinampa system of raised, flooded fields which would later be used so effectively by the Aztecs. Turkey and dogs were husbanded for food, and wild game included deer, rabbits, and peccaries, whilst wild plants, insects, frogs, and fish also supplemented a diverse diet. In addition, the city displays evidence of textile manufacturing and crafts production. Teotihuacan also had its own writing system which was similar to, but more rudimentary than, the Maya system and generally limited in use to dates and names, at least in terms of surviving examples.

At its peak between 375 and 500 CE, the city controlled a large area of the central highlands of Mexico and probably exacted tribute from conquered territories via the threat of military attack. Teotihuacan's fearsome warriors, as depicted on murals, carry atlatl dart-throwers and rectangular shields, and they wear impressive costumes of feather headdresses, shell goggles, and mirrors on their backs. Evidence of cultural contact in the form of Teotihuacan pottery and luxury goods is found in elite burials across Mexico and even as far south as the contemporary Maya centres of Tikal and Copan.

Mysteriously, around 600 CE, the major buildings of Teotihuacan were deliberately destroyed by fire, and artworks and religious sculptures were smashed in what must have been a complete changing of the ruling elite. The destroyers may have been from the rising city of Xochicalco or from within in an uprising motivated by a scarcity in resources, perhaps acerbated by extensive deforestation (wood was desperately needed to burn huge quantities of lime for use in plaster and stucco), soil erosion, and drought. Whatever the reason, after this climatic event, the wider city remained populated for another two centuries but its regional dominance became only a memory.

Teotihuacan Religion

The most important deity at Teotihuacan seems to have been, unusually for Mesoamerica, a female. The Spider Goddess was a creator deity and is represented in murals and sculpture and typically wears a fanged mask similar to a spider's mouth. Other gods, who would become familiar in subsequent Mesoamerican civilizations, included the Water Goddess, Chalchiuhtlicue, who is impressively represented in a three-metre high stone statue, and the rain and war god Tlaloc. Clearly, there was a preoccupation with life-giving water in such an arid climate. Other deities often represented in Teotihuacan art and architecture include the feathered-serpent god known to the Aztecs as Quetzalcoatl, Xipe Totec, who represented agricultural renewal (especially maize), and the creator god known as the Old Fire God. The positioning of temples and pyramids in alignment with the sun on the June solstice and the Pleiades suggests calendar dates were important in rituals, and the presence of buried offerings and sacrificial victims illustrates the belief in the necessity to appease various gods, especially those associated with climate and fertility.

Architectural Layout & Features

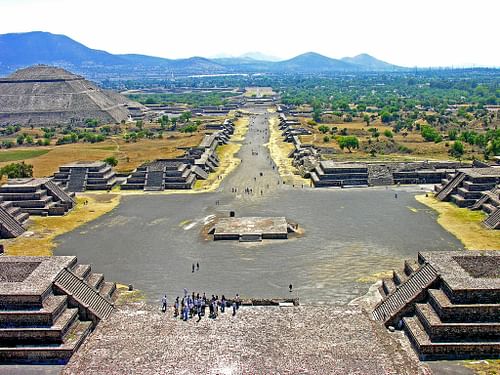

The city, covering over 20 square kilometres, has a precise grid layout oriented 15.5 degrees east of true north. The city is dominated by the wide Avenue of the Dead (or Miccaotli as the Aztecs called it) which is 40 metres wide and 3.2 km long. The avenue begins in agricultural fields and passes the Great Compound or market place, Citadel, the Pyramid of the Sun, many other lesser temples and ceremonial precincts, and, culminating at the Pyramid of the Moon, points towards the sacred mountain Cerro Gordo. Archaeology has discovered that the original avenue was much longer than is visible today and is dissected by another avenue which thus created a city of four quarters. The site is dominated by the two great pyramids of the sun and moon and the Temple of Quetzalcoatl, but most buildings were more modest and take the form of small groups of buildings (over 2,000 of them) organised around a courtyard and the whole surrounded by a wall. It was here in the compound that daily cooking was done using clay braziers. Many compounds have one or two burial spaces suggesting that each was a family or kin group, and some cover several thousand square metres and so may be better described as palaces. Other compounds are more modest and use less fine building materials so that they may have been workshops for artisans. Many compounds also have large cisterns offering the possibility of independent water supply. The city had ethnic zones: Zapotecs in the western area and Maya in the eastern, for example. Typical features of the site's architecture include single-storey structures, flat roofs with occasional open portions, and decorative vertical rectangular panels set on a sloping support wall (talud-tablero) which were inset into the sloping facades of all types of religious buildings and which were much copied across Mesoamerica.

Pyramids of the Sun & Moon

The five-level Pyramid of the Sun was actually built over a much earlier sacred tunnel-cave and natural spring. The structure, constructed c. 100 CE, has six platforms and measures 215 metres along the sides and towers 60 metres high, which made it one of the biggest structures ever built in the ancient Americas. The present exterior, which would have once had a facing of smooth lime plaster, covers a slightly smaller earlier pyramid built over a massive mud-brick and rubble interior. The top once had a small temple structure, reached by a flight of stone stairs climbing the entire pyramid and which split and rejoined higher up. Inside the pyramid is a 100 metre-long tunnel which leads from beneath the outside staircase to a four-winged chamber, unfortunately, looted in antiquity but probably once a burial chamber or shrine.

The Pyramid of the Moon is very similar to, albeit slightly smaller than, it's neighbour the Pyramid of the Sun. The present exterior covers six progressively smaller pyramids. Constructed c. 150 CE there is no inner chamber as in the Sun pyramid, but the foundations did contain many dedicatory offerings such as obsidian and greenstone felines and eagles and a single person. Offerings were also buried at each subsequent construction stage. And three males were buried just beneath the summit; the accompanying precious jade objects suggest they were important Maya nobles. There are also the remains of sacrificed animals including pumas, rattlesnakes, and birds of prey.

The Citadel & Temple of Quetzalcoatl

The Citadel (Ciudadela) royal residential complex is dominated by the Temple of Quetzalcoatl, a celebration of warfare. The latter was constructed c. 200 CE and, although once partially covered, is richly decorated with sculptures of feathered-serpent and Tlaloc-like heads. These decorative elements were once brightly painted in blue, red, yellow, and white. The pyramid has seven levels, and over 200 non-local males and females were sacrificed to commemorate its completion. Amongst these were two groups of 18 young warriors who, with hands tied behind their backs, were sacrificed and buried in two large pits on the north and south sides of the building. At each corner of the pyramid another victim was buried, and in the heart of the structure another 20 sacrificial victims were buried along with a vast horde of precious objects. The numbers are significant as each of the calendar months had 20 days and there were 18 months in the Mesoamerican year. In addition, at the heart of the temple are two burial chambers which were emptied, perhaps by the residents of Teotihuacan c 400 CE, but one remaining feathered-serpent baton suggests that the occupants were rulers. Also deserving of mention is the Quetzalpapalotl Palace. This structure is one of the latest at Teotihuacan and forms an enclosed columned courtyard. The building is richly decorated with relief images of owls and quetzals, representative of warfare.

Teotihuacan Art

The art of Teotihuacan, as represented in sculpture, pottery, and murals, is highly stylized and minimalist. Stone masks were made using jade, basalt, greenstone, and andesite, often highly polished and with details, especially eyes, rendered using shell or obsidian. These masks were also made in clay, and both types would once have adorned statues and mummy bundles. A great many buildings at Teotihuacan were decorated with murals, most of which portray religious events, especially processions, but also scenes with details of landscape and architecture and especially watery scenes such as fountains and rivers. Scenes also include gylphs suggesting the existence of a writing system, even if much less varied and sophisticated than that used by the contemporary Maya. Painted using the true fresco technique, the work was then given a final polish. Bright colours were used and shades of red were especially popular and used to most often depict gods, sacrifices, and warriors. In the more modest buildings, repeated patterns were also painted using stencils to create an effect much like modern wallpaper.

Typical Teotihuacan pottery vessels are the round dishes with three rectangular feet and a lid, and bulbous vases sparingly decorated with geometric designs. Other popular forms include intricate incense burners and dynamic figurines, both of which have mould-made additions and stamped decorations which suggest a degree of mass-production. The best Teotihuacan pottery was made with thin-walled orange clay, decorated with stucco, and was much in demand across Mesoamerica.

Sculpture was made in all sizes but never captures individual likenesses. Rather, the focus is on generic forms and stylistic conventions, chiefly in the representation of gods such as the huge Great Goddess statue, from basaltic lava and standing 3.2 metres high, discovered near the Pyramid of the Moon and dating to before 300 CE. Imagery relating to the rain god Tlaloc was also popular in Teotihuacan sculpture which was made without the use of metal tools.

The Legacy of Teotihuacan

Aspects of Teotihuacan's religion, monumental architecture, urban planning, and various features of the city's art would influence both contemporary and subsequent civilizations across Mesoamerica, including the Zapotecs, Maya, Toltecs, and Aztecs. Imagery such as the feathered-serpent god and the owl representative of warfare are just two examples of Teotihuacan iconography that became ubiquitous across Mesoamerica. Teotihuacan cast a long cultural shadow through history and, 1,000 years after its peak, the last great Pre-Columbian civilization, the Aztecs, revered the city as the origin of civilization. They believed Teotihuacan was where the gods had created the present era, including the fifth and present sun. The Aztec king Montezuma, for example, made several pilgrimages to the site during his reign in homage to the gods and the early rulers of Teotihuacan, who were "wise men, knowers of occult things, possessors of the traditions" and whose tombs were the site's great pyramids, built for them, according to legend, by giants in the distant but not forgotten past.