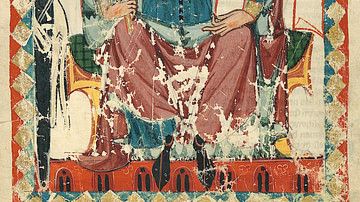

A medieval Teutonic Knight was a member of the Catholic military Deutscher Orden or Teutonic Order, officially founded in March 1198 CE. The first mission of the Teutonic knights was to help retake Jerusalem from the Arabs in the Third Crusade (1187-1192 CE), and during this failed attempt they set up a hospital outside Acre during the siege of that city. The hospital was granted the status of an independent military order by the Pope, and the knights never looked back. The Middle East proved to be too difficult to hold onto, but the ambitious order merely switched their focus to converting Christians and grabbing land in central and eastern Europe instead. With their famous black cross on a white tunic, the austere Teutonic knights became master traders and diplomats, carving out vast swathes of territory from their base in Prussia and building castles across Europe from Sicily to Lithuania.

Foundation: The Third Crusade

The Third Crusade was called by Pope Gregory VIII following the capture of Jerusalem in 1187 CE by Saladin, the Sultan of Egypt and Syria (r. 1174-1193 CE). Although led by the cream of Europe's nobility, the project was beset with problems, none bigger than the accidental death en route of Frederick I Barbarossa (King of Germany and Holy Roman Emperor, r. 1152-1190 CE). Barbarossa's untimely drowning resulted in most of his army trudging back home in grief, but some German knights pressed on and assisted in the siege of Acre which terminated in July 1191 CE. Despite other successes, the Crusaders only managed to get within sight of Jerusalem and no attempt was made to attack the holy city. Instead, control of a small strip of land around Acre was negotiated and the future safe treatment of Christian pilgrims to the Holy Land.

At Acre, c. 1190 CE, a body of German knights had founded a field hospital (as their fellow nationals had done in Jerusalem in the 12th century CE) dedicated to Saint Mary. In March 1198 CE Pope Innocent III (r. 1198-1216 CE) granted its members the status of an independent military order under the name Fratres Domus hospitalis sanctae Mariae Teutonicorum (Brethren of the German Hospital of Saint Mary). Thus the organisation was born which would later become much better known as the Teutonic Order and its members as Teutonic knights. Like other military orders of the medieval period (e.g. the Knights Templar and Knights Hospitaller), it was a combination of two ways of life: knighthood and the monastery.

The order acquired land in parts of the Crusader-controlled Middle East, and established a handful of castles, especially around Acre. Essentially, the order was meant to defend Crusader acquisitions. In addition, the order had land in Cilicia thanks to their close relationship with the Armenians there who saw them as a counterbalance to the Templar Knights. The headquarters of the order was established at the Montfort fortress (Qal'at Qurain) in the hills of Galilee, north-east of Acre, with the Teutonic knights renaming the castle Starkenberg. The order had two important fortresses in eastern Cilicia and would steadily acquire more lands, including territories in Greece, Italy, and central Europe.

Organisation & Recruitment

The order was led by a Grand Master (Hochmeister) who was chosen by an electoral college and who was expected to consult his senior officers and commanders. In the 15th century CE, there was a second master in Livonia who became increasingly independent from the order based at its then headquarters in Prussia. It did sometimes happen that a master was ousted by his officers, indeed there was one case of murder of a particularly unpopular master. The order controlled many lands across Europe and the Middle East, the territories spilt into administrative provinces or balleien, each governed by a landmeister.

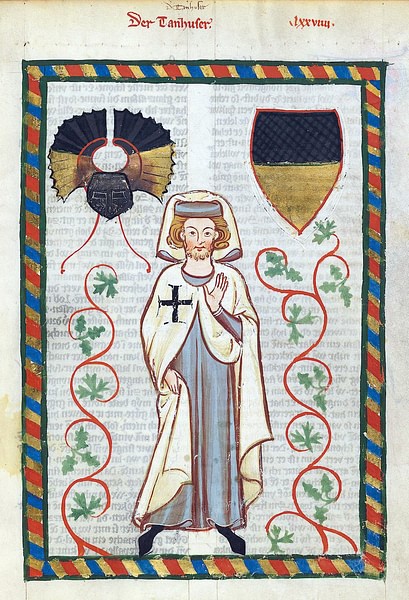

Most recruits to the many castle-convents spread across Teutonic territory were Germanic, coming from Franconia and Thuringia, the Rhine, and other German territories. The knights (ritter) or brothers, typically aristocrats although usually members of its lower echelons, were spread around many commanderies containing anywhere from 10 to 80 members. As in other military orders, recruits took monastic vows of poverty, chastity, and obedience. Motivation to join included the rewards in the next life promised to those who crusaded in the name of God, the chance for adventure and promotion, and even simply regular meals and a place to sleep.

German settlers could enter the order but usually only as priests or serving half-brethren (halb-brüder). Each castle-convent would also have had a contingent of local crossbowmen and non-combatants such as servants and craftsmen. Finally, foreign knights were not unknown as the order was officially international, although most recruits came from German lands. The total membership of the brotherhood fluctuated depending on battles and territories won or lost. In Prussia, for example, there were 700 members in 1379 CE, 400 in 1450 CE, 160 in 1513 CE, and 55 in 1525 CE. The total number of knights across the order likely never exceeded around 1,300.

The order gained income from booty taken in warfare and from captured territories, but there was also a significant and regular stream of funds from trade and land rents, as well as donations which might be in the form of cash, goods, or land. Some knights-brethren were expected to pay a fee on entry and taxes on local populations were introduced into Teutonic territories in the 15th century CE. This became necessary as the order required more knights than it could actively recruit and so was forced to pay mercenaries to achieve its objectives. Commanderies offered training, residences, and a place of retirement for members of the order, as well as help to local communities through their hospices, hospitals, schools, and cemeteries. The order also built churches, maintaining them and supporting artists to decorate them.

Uniform & Rules

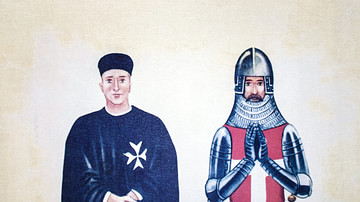

The order was, above all, famous for its well-trained and well-armed knights, as well as their stout stone fortresses. Teutonic knights wore black crosses on a white background or with a white border. These crosses could appear on shields, white surcoats (from 1244 CE), helmets, and pennants. Half-brethren wore grey instead of the full white reserved for knights.

The Teutonic knights had to follow a good many strict rules, more than in other military orders. Beards were permitted but not long hair and any ostentatious clothing or equipment were frowned upon. Knights were not allowed money or personal property, even their limited clothing could not be kept in a locked chest. Unlike other orders, prior to the 15th century CE, the Teutonic knights did not go in for personal seals and burial monuments. Personal coats of arms were forbidden. Another no-no was any excessive entertainment (one might argue of any sort at all, excessive or otherwise). Knights could not joust in medieval tournaments, not mix socially with other types of knights, and they could not engage in most types of hunting. Tedium could be kept at bay by the one hobby that was allowed: woodcarving.

European Crusades: Prussia & Livonia

Disaster struck the order in 1244 CE when the Kingdom of Jerusalem fell to the Ayyubid sultan of Egypt. At the battle of La Forbie near Gaza, a devastating 437 of 440 Teutonic knights were killed. In 1271 CE the Mamluks of Egypt and Syria captured Montfort fortress, effectively removing Teutonic influence in the Middle East, although they clung onto a new headquarters at Acre until the city's fall in 1291 CE, again to the Mamluks. Under a new Grand Master, Conrad von Feuchtwangen, the order relocated to Venice. Then, in 1309 CE, under the new master Siegfried von Feuchtwangen, the headquarters was moved again, this time to a fortified convent at Marienburg in Prussia. This was a more practical location for the order's abandonment of Middle East affairs and its focus on northern and central Europe, where the knights had already been on campaign (Hungary in the first decade of the 13th century CE and Prussia from 1228 CE).

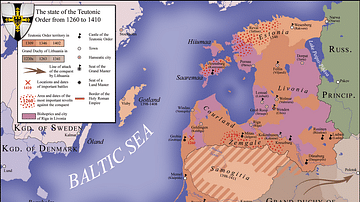

Throughout the 13th and 14th century CE the Catholic Teutonic knights crusaded in Prussia and the Baltic area mainly against pagan Lithuanians and Orthodox Russians, but as the order was bent on expansion for its own sake, many other nationalities were fought besides those. The long-disputed territory between Prussia and Livonia was a particularly happy hunting ground, and the Teutonic knights eventually came to govern the whole of Prussia. There were several revolts by Prussians under Teutonic rule, notably in 1260 CE, and the ongoing wars were savage. There were serious military setbacks, too, notably to the Russians at Lake Peipus in 1242 CE. The order was not without controversy either, receiving accusations of less-than Christian policies towards fellow believers. Teutonic knights were accused of slaughtering Christians in Livonia, trashing secular churches, impeding conversions, and trading with heathens. Indeed, it has been said that many pagans in central Europe resisted Christianization only because they did not want to live under the menacing cosh of the Teutonic knights. In 1310 CE the pope launched an investigation, but nothing came of it, and the order withstood the damage to its reputation. There was also some recognition that the rumours were being spread by the order's rivals and enemies.

The Teutonic order was successful in gaining new territory, notably Danzig and eastern Pomerania in 1308 CE and northern Estonia in 1346 CE. There was a major victory against the Lithuanians, and the prestige of the order's campaigns in Prussia and Livonia attracted nobles from across Europe, including the future Henry IV of England (r. 1399-1413 CE). However, when the Lithuanians formally converted to Christianity in 1389 CE, the ideal of crusading lost its purpose. Thereafter, it became clear that the Teutonic Knights were mostly interested in politics and booty rather than conversion as the wars continued. When the Lithuanians and Poles joined forces with the Russians and Mongols, along with several other smaller allied states, the Teutonic order was threatened with extinction. At the battle of Tannenburg, 15 July 1410 CE, an army of Teutonic Knights was wiped out, and in 1457 CE the headquarters of a now much-reduced and largely secular order had to be relocated to Konigsberg. The Teutonic order still continued at its Livonian branch into the 16th century CE, which now primarily focused on battling, without much success, schismatic Russians and Ottoman Turks. The secularized order (from 1525 CE in Prussia and 1562 CE in Livonia) continued to exist as a minor military unit, fighting in the German and Austrian Habsburg armies into the 18th century CE, and it still exists today as a non-military organisation supporting communities with healthcare, welfare projects, and the sponsorship of artists. The order's archives, now in Vienna, are an invaluable historical source on the medieval period and the functioning of military orders in general.

Achievements

The Teutonic order enjoyed many successes over the centuries, as well as military failures - notably in the defence of the Holy Land and against the Russians, but it achieved the two things it was always meant to do: spread Christianity and help the poor and needy. The order converted a great number of pagans wherever they conquered territories, then settled those places with migrant Germans as part of a systematic colonisation. The order spread technology, for example building a huge watermill at Danzig in the early 14th century CE. Their trading skills were renowned across Europe, as were their diplomacy skills which led to one old German proverb: “If you're so clever, go and deceive the lords of Prussia”. In a sense, the order was a victim of its own success as its administrative and trading skills often brought it into conflict with other powers. Further, when traditional opponents converted to Christianity, the chief purpose of the Teutonic order no longer existed.