The Thames Tunnel was completed in 1843 and connects the two banks of the River Thames at Rotherhithe and Wapping in London. The 20-year project was masterminded by Marc Isambard Brunel (1769-1849) and was both the first tunnel to be built under a major body of water and the first to use a tunnel shield during its construction.

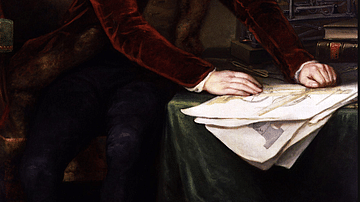

Marc Isambard Brunel

In 1820, the only crossing of the River Thames in London was the narrow London Bridge, and another crossing point was desperately needed to relieve the traffic congestion in the capital (Tower Bridge was not built until 1894). Building a second bridge further downstream would have blocked access by shipping and so the obvious if seemingly impossible alternative was a tunnel. Large tunnels had been built in various parts of Britain's canal network, but the idea to tunnel under a major river was a first. The greatest problem the project faced was how to prevent the tunnel from flooding during the construction stage. Three attempts were made to build a tunnel, including one by the noted engineer Richard Trevithick (1771-1833) in 1807, but all three projects ended in floods and disaster.

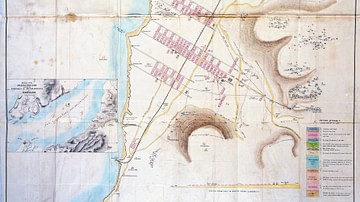

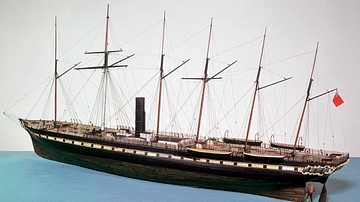

The inventor and engineer Marc Isambard Brunel was the genius behind the successful Thames Tunnel, but it would prove to be an extraordinarily difficult project to complete, not least because of the scale of the construction and the terrain, an unhelpful mixture of clay, gravel, mud, and quicksand. Brunel had already designed a tunnel for a proposed project in St. Petersburg in Russia, but the idea was not taken up by the authorities there. Brunel believed he could make the Thames Tunnel a reality, and in 1818, he joined forces with Thomas Cochrane, Earl of Dundonald (1775-1860) to patent a device that would prove essential to the project: a tunnelling shield. The device may have been inspired by the shipworm (Teredo navalis) which burrows into the wooden hulls of ships. The shipworm's soft interior is protected while it bores by a hard outer shell around its gnawing jaws and head. Brunel's idea was that a shield would act as a temporary support for a stretch of the excavated area until a more solid covering of the tunnel could be put in place. This was an essential precaution in soft or waterlogged ground, which might easily collapse while men were excavating the tunnel.

Meanwhile, the failure of one of Brunel's companies in 1821 meant that he spent some time in a debtor's prison in Southwark, but by 1822, he was a free man and ready to once again take up the challenge of the Thames Tunnel project. In 1823, Brunel was made the chief engineer of the project, and he tweaked his tunnel shield design to specially cater for the challenges of tunnelling under the Thames. It was the famed Maudslay factory in Lambeth, London, that made Brunel's tunnel shield into a physical reality. Run by Henry Maudslay (1771-1831), the Lambeth factory was, in many instances, the crucible where engineering ideas of the British Industrial Revolution were forged into reality. Maudslay completed the 80-ton tunnel shield in 1825. It was a large rectangle of iron scaffolding. The shield measured around 11 metres (36 ft) across and had a height of 6.5 metres (21 ft 4 in). The idea was that workmen on three levels would remove a wooden board in front of them, excavate 10 cm (4 in) of the earth, and then replace the board. The platform allowed 36 men to work simultaneously. The whole iron structure would be inched forward using screw jacks as every four inches of progress was made.

Construction Problems

The Company charged with building the tunnel, the Thames Tunnel Company, was formed in February 1824, and work began that same year. The project was funded by private investors who hoped to receive dividends once the tunnel was opened and users started to pay the passage toll for the convenience of using it. On 2 March 1825, the first stone was laid at the Rotherhithe shaft entrance.

Another innovation for the project was the tower used to create the large vertical entrance shafts at either end. The hollow tower had workmen inside, and it descended under its own weight (100 tons), with its bottom iron cutting edges cutting into the ground as the men dug down into the soil. Excavated material was taken to the top of the tower using a chain of buckets which was powered by a steam engine. Each entrance shaft measured around 15.2 metres (50 ft) in diameter and went down about 21.3 metres (70 ft). The shafts were then lined with bricks before being faced with stone. Steps were to be made for pedestrians to descend while wheeled vehicles would use great spiral ramps, which Brunel called "Great descents".

Once the vertical shaft had been dug, the tunnel shield could be brought in, and work started on moving horizontally under the river on 28 November 1825. As the shield inched forward, men lined the tunnel with bricks to create two parallel passageways. Light was provided by gas lamps. It was a complex but well-thought-out arrangement of men and materials. The project was estimated to take three years, which turned out to be optimistic, mostly due to the soil not being as consistent as the exploratory shafts had shown it might be. Still, the numbers involved were impressive:

In all, 500 men typically worked the tunnel at any one time, their shifts 16 hours one day and 8 the next, comprising not merely miners and bricklayers but blacksmiths, carpenters, riggers, millwrights and labourers ... They would get through 70,000 bricks a week, 350 casts of cement, 300 lbs of candles and would cart 750 tons of spoil from the works.

(Waller, 55)

Despite the men working in the shield doing well, there were some serious setbacks to be faced. The first problem was the long history of the Thames River. The river had been used as a refuse dump and sewer for at least a millennium, and the accumulated gunge the excavators came across was overpowering. "Men fainted at the Shield face, and were carried off suffering from dizziness, chest pains, impaired vision and suppurating arms" (Cruickshank, 48).

The tunnel flooded twice. The first flooding came on 17 May 1827 when the excavators reached a particularly thin patch between themselves and the river bed. The proximity of the mass of water above was confirmed when Brunel's son Isambard descended in a diving bell into the murky depths of the Thames. The gap was plugged by sinking a wooden raft onto that part of the river bed and then around 150 tons of clay sacks were dropped on top.

The tunnel shield and the tunnel had been badly damaged in the flooding, and it took four months to get the excavations going again. In November, with that bravura and showmanship typical of grand Victorian engineering projects, Brunel organised a banquet in one of the half-complete tunnels, which was festooned with red drapery. The diners could see themselves thanks to a plethora of silver candelabras but probably struggled to hear each other over the din of a Coldstream Guards band. The celebrations proved to be premature.

The second flood occurred on 12 January 1828. This was more serious than last time, with six workers losing their lives. Once again the blocked-up tunnel had to be redug, and the tunnel shield repaired. Accidents were not limited to the labourers. Isambard Brunel, who had been appointed the resident engineer of the project the year before and who was somewhat accident-prone, suffered serious injuries when he fell into an uncovered water tank in October 1827. Isambard recovered but was caught in the massive wall of water that crashed into the tunnel in the January flooding; the engineer was only just saved from drowning.

A new improved version of the shield was built, and tunnelling finally resumed in August 1828. The project was certainly a challenging one, and there were many more periods of delays over the next decade. In July 1834, the government gave a much-needed cash injection of £270,000. The money was only a loan, but it permitted Brunel to perfect a more efficient design of his tunnel shield, and work resumed again in March 1836. The tunnel had become a prestige project of national importance; work had to go on, whatever the cost.

There were four more episodes of serious flooding and several damaging fires. Another problem was the build-up of dangerous gases like methane. The project was taking so long to complete, the press labelled the tunnel the 'Great Bore'. The tunnelling stage continued, nonetheless, and was eventually completed in November 1840. Brunel was awarded a knighthood for his efforts by Queen Victoria on 24 March 1841. The queen was impressed by the engineering feat but less so by the conditions she was subjected to, as she noted in her diary after her visit: "One goes down a long way and then enters the tunnel, which was lit by gas ... It was excessively hot both going and returning" (Waller, 61). The final construction stage was completed by 1842. The many delays over the years meant that the costs of the project rocketed to over £630,000 ($75 million today).

Completion & Uses

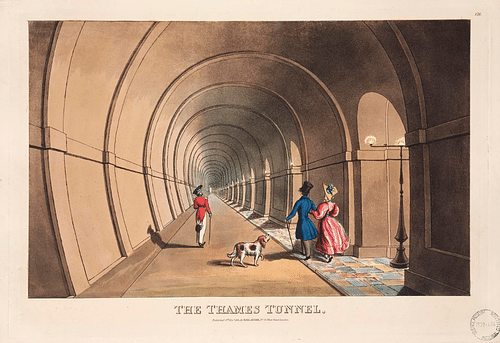

The Thames Tunnel was officially opened on 25 March 1843. It measured 396 metres (433 yds) in length and was 6 metres (19.5 ft) high and 11 metres (36 ft) wide. The greatest depth was over 23 metres (75 ft) below the surface of the River Thames. The interior of the tunnel, typical of the times, was rather more splendid than it need be to complete its function, with plenty of decorative elements of Roman architecture in the Neoclassical style. A silver medal was struck to commemorate the opening of the tunnel, and it showed on one side the twin tunnels of the Wapping entrance and a profile portrait of Marc Isambard Brunel on the other.

The tunnel had gone so over budget that the original plan to permit horse-drawn vehicles to use it was never realised since it was too expensive to build the necessary access ramps. For now, the tunnel was limited to use by pedestrians, who paid one penny for the experience. It was a popular attraction and, for some, a shortcut to the opposite bank of the Thames. Another reason to see the tunnel was the 63 stalls set in the brick arches, which made it a sort of entertainment pier below ground. One could buy various goods and souvenirs, take refreshments, see information displays, and listen to a steam-powered organ. "Some 50,000 people queued up to walk through on the first day; more than a million sightseers visited within 15 weeks of its opening, and 2 million over the first nine months. Revenues from this foot traffic amounted to nearly ten thousand pounds a year" (Waller, 61). This was not, however, enough to cover the tremendous construction costs, pay back the initial capital investors, or refund the government for its 1834 loan.

To squeeze yet more pennies from the public, an annual fair was organised in the tunnel, which lasted three days and attracted over 65,000 visitors from Britain and abroad. Inevitably, perhaps, the novelty of the tunnel wore off, especially for Londoners, and the tunnel became less frequented by passing pedestrians and more the haunt of prostitutes and pickpockets.

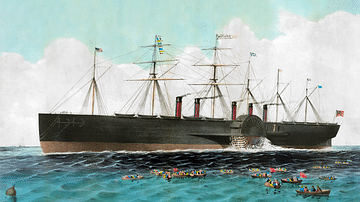

It was not until 1865, when it was bought by the East London Railway Company for a third of the cost to build it, that the tunnel was finally to be used by trains. Even then it took four more years before the first train ran through the Thames Tunnel on 7 December 1869. The London Underground used the tunnel from 1913.

The Thames Tunnel is still used by trains today as part of the London Overground network. Brunel's idea of the tunnel shield was probably much more influential than the tunnel itself and is still widely used in cylindrical form (as Brunel himself had originally designed it, in fact) on modern underground construction projects worldwide. At the Rotherhithe end in a small engine house, there is now a museum dedicated to the history of the tunnel once described as the wonder of the Industrial Revolution.