The Eumenides is a play written by Aeschylus (c 525 – 455 BCE), the “Father of Greek Tragedy,” the most popular and influential of all tragedians of his era. The Eumenides was the third play of a trilogy, The Oresteia, with the remaining two tragedies being Agamemnon and Libation Bearers. There was also a satyr play, the lost Proteus.

In first play Agamemnon, the victorious king of Argos has returned home after the Trojan War, bringing with him a concubine, Cassandra. Agamemnon's wife Clytemnestra and her lover Aegisthus, hoping to rule Argos together, have conspired against him to kill him upon his return. In the queen's mind, the murder of her husband was simply an act of revenge for the earlier death of her daughter. In Libation Bearers, the exiled Orestes, son of Agamemnon and Clytemnestra, returns home with his companion Plyades to seek revenge for this father's death by killing his mother and lover. However, his mother's last breath brings a curse upon Orestes: he is hounded by the Furies. In Greek, they are later referred to as the Eumenides, daughters of the night and spirits of vengeance. In The Eumenides, Orestes, on the verge of madness, prays to Apollo for relief from his agony. Eventually, he and Apollo arrive in Athens where the goddess Athena holds a trial.

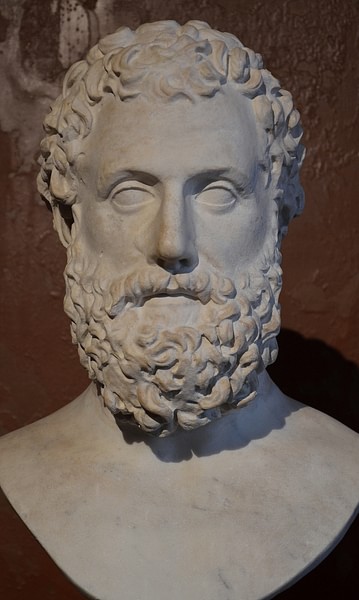

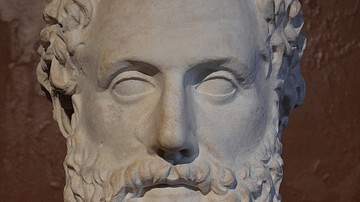

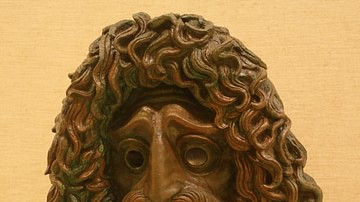

Aeschylus

Aeschylus was born into an aristocratic Greek family of Eleusis, an area west of Athens. Deeply religious and a strong proponent of Athenian democracy, he fought at the Battle of Marathon in 490 BCE and may have also fought at the Battle of Salamis in 480 BCE. He began producing plays in the 490s BCE, winning his first victory in 484 BCE. Of his over 90 plays, only six have survived; the authorship of a seventh Prometheus Bound is in question. His trilogy Oresteia won a first at Dionysia in 458 BCE. Eventually, he won a total of 13 victories, second only to Sophocles. Although little is known of his personal life and family, his sons Euphorion and Euaion also became playwrights.

While he lived most of his life in Athens, he was invited to the city of Syracuse on the island of Sicily by King Hieron. Continuing to write until the end of his life, he would die there in 455 BCE. He is credited with taking Greek tragedy in a new direction, completely revolutionizing it. Prior to Aeschylus, a play's dialogue was hampered with only one actor. With his introduction of a second actor and possibly a third, plot construction was given far more freedom and the complexity of plays increased. Unlike many other playwrights, Aeschylus may have also designed costumes, trained his choruses, and possibly even acted in some of his own plays.

The Myth

As with many of the Greek tragedies, the audience was well aware of the legends surrounding the play. In this instance, the stories of Homer's Iliad and Odyssey are the prelude to all three of Aeschylus's three plays. Somewhat radical in politics and religion, Aeschylus' plays often contain strong political themes. Like other tragedians, his plays were written for competitions at rituals and festivals and performed in outdoor theaters. The purpose of these tragedies was to entertain as well as to enlighten the Greek citizen, to explore a political, social, or ethical problem. Since all three of the plays would have been performed on the same day at the Dionysia, most in the audience would already know of the circumstances behind Agamemnon's gruesome death and Orestes' ordeal when the last play is finally performed.

Characters

The cast of characters for The Eumenides includes:

- the Pythian priestess of Apollo

- Apollo

- a silent Hermes

- Orestes,

- the ghost of Clytemnestra,

- Athena

- a Chorus of Furies

- silent Jurymen

- and a second chorus of Athenian women.

Plot Summary

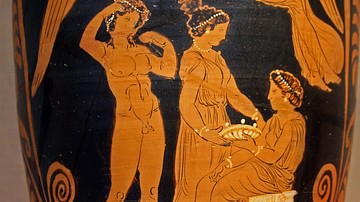

The play's setting is in two places. The first is in front of the sanctuary of Apollo while the second is at the Acropolis before the temple of Athena. Before entering the temple of Apollo, the Pythian priestess addresses the audience:

I call upon the springs of Pleistus, on the power of Poseidon and on final loftiest Zeus, then go to sit in prophecy on the throne. May all grant me that this of all my entrances shall be the best by far. (Grene, 124)

Her prophecy will be guided by the gods. Upon exiting the temple and crawling on all fours, she sees Orestes “with god's defilement on him postured in the suppliant's seat with blood dripping from his hands and from a new-drawn sword” (125). Terrible things to tell and see have driven her from the temple. She has no strength and can barely stand. In front of her are the Furies, asleep with ooze dripping from their eyes. She speaks:

… the master of the house must take his own measures: Apollo Loxias, who is strong and heals by divination, reads portentous signs and so purifies the houses others hold as well. (125)

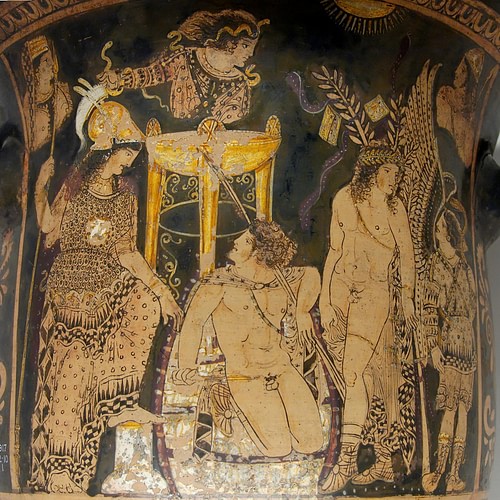

She leaves as the temple doors open, and the gods Apollo and Hermes stand beside Orestes. Apollo speaks to Orestes of how he has silenced the Furies, putting them to sleep. He confesses to Orestes that it was he who made him kill his mother, but he promises to stand by his side and not give him up. Turning to Hermes, he tells the winged messenger god to shepherd Orestes “with fortunate escort on his journeys among men. The wanderer has rights which Zeus acknowledges” (126). Apollo exits into the temple.

Suddenly, the ghost of Clytemnestra appears before the sleeping Furies; Orestes and Hermes stand off to the side. She accuses the Furies that it is their fault she goes dishonored among the dead. She is driven in disgrace. No one sees or understands how she has suffered. As she speaks, the Furies begin to awaken. Clytemnestra rebukes them with apparent anger at Orestes:

… your man has got away and gone far. He has friends to help him, who are not like mine. ... Let go upon this man the storm blasts of your bloodshot breath, wither him in your wind, hunt him down once more, and shrivel him in your stomach's heat and flame. (127-8)

The ghost disappears as Apollo emerges from his temple and immediately tells the awakened chorus of Furies to leave. Speaking on behalf of the Furies, the chorus leader questions the god about Orestes, saying “You gave this outlander the word to kill his mother” (130). Apollo admits his guilt but adds that he has also given him refuge in his house. The leader replies that they have the sworn duty to drive matricides out of their houses. Apollo answers with a question; what about Clytemnestra's killing of her husband? The leader responds that the first murder was not the “shedding of kindred blood” (130). Apollo challenges him:

If when such kill each other you are slack so as not to take vengeance nor eye them in wrath, then I deny your manhunt of Orestes goes with right. (131)

He continues stating that one death causes the Furies to take action in rage while another is ignored. The leader disregards Apollo's plea and says that nothing with allow Orestes to go free. Apollo promises to help Orestes for if he does not who else will turn to him for help. Finally, he says that the goddess Athena, Pallas divine, will decide the case. It is at this point that the setting of the play is changed from the temple of Apollo to the temple of Athena in Athens.

Orestes, standing before the temple, addresses the statue of the goddess Athena, patron of the city of Athens. He says that the stain of blood fades from his hands, the stain of matricide is being washed away. He begs the goddess rescue him. The chorus leader interrupts Orestes' plea, saying that neither Apollo nor Athena can free him. Suddenly, the goddess Athena herself appears and speaks to both Orestes and the Furies and tells them that her temple is the place of the just, and “Its rights forbid to speak evil of another who is without blame” (138). The chorus leader identifies himself and the other Furies as “children of the night.” He informs the goddess that their duties are to drive from home those who shed another person's blood and take him to a place where “happiness is nevermore allowed.” He identifies Orestes as having killed his mother by deliberate choice and asks that Athena decide his fate. Athena turns to Orestes, asking for a plain answer. He does not deny his actions but tells her the story of the death of his father Agamemnon and how his mother had killed him:

It was my mother of dark heart, who entangled him in intricate nets and cut him down. ... This was vengeance for his blood. (140-1)

He adds that Apollo shares responsibility for his action, however, he will place himself in her hands. Having listened to both sides, Athena says that she understands the concerns of Orestes and the duties of the Furies, so she will select a jury to hear the case. Both litigants are told to prepare their arguments. She exits, soon returning with eleven citizens.

Shortly, a trumpet sounds. Apollo enters and addresses the court. He testifies that he has cleansed Orestes of the stain of blood and will help him win his case, adding that he bears responsibility for Orestes's mother's death. Orestes speaks to the jury:

Yes, I killed her. There shall be no denying of that. (145)

The chorus leader confronts him by asking how she had been killed. Orestes responds that it was with a sword; he slit her throat but, in answer to the leader's challenge, it was Apollo who guided his hand. He tells the court how his mother had murdered his father, her husband. He asks the chorus leader why he had not descended upon her after she committed murder. He responds that her murder of Agamemnon was not of congenital blood; she was not his mother, therefore no blood bond. Hearing this, Orestes questions whether or not he shares a blood bond with his mother.

Apollo intervenes; as a god he cannot lie. He tells the jury that Agamemnon had returned from the Trojan War victorious and Clytemnestra lay in wait for him and then killed him in his bath. However, in a challenge to the leader's appeal on the issue of a blood bond, the wise Apollo then states that a mother is not a parent of the child but only a “nurse of the new-planted seed” (148). There can be a father without a mother. He reminds the court how Athena, herself, was born without the aid of a mother. He then asks the jury to cast their votes. Athena turns to the jury and speaks:

I advise my citizens to govern and to grace, and not cast fear utterly from your city. What man fears nothing at all is ever righteous? Such be your just terrors, and you many deserve and have salvation for your citadel…. (149)

She then tells each man to think on the oath he has made and make his judgment. The eleven jurors walk forward and cast their ballots. However, Athena asserts that it is her duty to make the final judgment, and she casts her ballot for Orestes.

So, in the case where a wife has killed her husband, lord of the house, I shall not value her death more highly than his. And even if the votes are equal, Orestes is the winner. (151)

The votes are tallied, and they are even. Orestes, now a free man, pledges to return home and promises that his country will never attack Athens. He leaves to return to Argos as king. After Orestes leaves, the chorus of Furies is visibly upset. Athena rebukes them and says they were beaten by a fair ballot but asks that they not bring hatred upon Athens. She adds:

… do not render it barren of fruit, not spill the dripping rain of death in fierce and jagged lines to eat the seeds. (153)

She promises them a place of their own, deep underground where they shall sit on shining chairs and accept devotions from the citizens of Athens. She asks that they do not cast spells upon the land and, instead, share in her “pride of worship.” She asks that they “do good, receive good, and be honored as the good are honored”(155). She promises that no house will be prosperous without their will, saying “You can be landowners in this country, if you will, in all justice, with full privilege” (156). In the end, the Furies, now known as the Kindly Spirits, accept Athena's offer and replace their black robes with reddish-purple ones. Although they will still seek vengeance against evil-doers, they will now also aid the good people of Athens.

Interpretation

Like the other two plays of the trilogy, The Eumenides is about justice. Orestes killed his mother out of revenge for the murder of his father, an act he deemed to be justified. Unfortunately, the curse of Clytemnestra brought the Furies, the spirits of vengeance, to drive him into madness. To them Orestes has committed matricide; there can be no excuse for that. Orestes flees to the Oracle of Apollo and later to the Temple of Athena to find solace and be freed of the curse. In a trial by jury, and with the help of the goddess Athena, he is finally free to return to Argos to rule as king. Justice has been served. With his return to his home, the curse that has haunted his family for generations has also ended. In the end, the Furies are transformed from spirits of vengeance to beneficent beings.