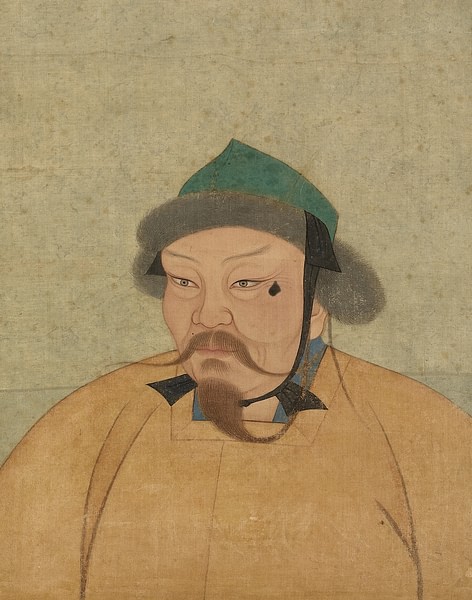

The Secret History of the Mongols is a chronicle written in the 13th century CE (with some later additions) and is the most important and oldest medieval Mongolian text. The book covers the origins of the Mongol people, the rise to power and reign of Genghis Khan (r. 1206-1227 CE) and the reign of his son and successor Ogedei Khan (r. 1229-1241 CE). Written from a Mongolian perspective, unlike most other medieval sources on the Mongol Empire, the work is an invaluable record of their legends, oral and written histories and, with its treatment of Genghis Khan and his imperial orders, it gives a unique insight into one of the most important leaders in world history. The title includes the word 'secret' because either only members of the imperial family and those given special favour or only Mongols were permitted to read it, even if other versions were in circulation in some remote places like Tibet.

Dating

The Secret History of the Mongols was written in the 13th century CE with some parts perhaps being written as early as 1228 or 1229 CE as indicated in the surviving colophon. The precise date of composition is not mentioned explicitly in the text but rather as the 'year of the Rat.' Fortunately, the date is further alluded to as the time of the great kurultai on Kode island, a meeting of senior Mongol tribal leaders to elect a new khan. This is most likely the meeting that formally elected Ogedei Khan in 1228 CE (a title he at first refused but accepted the following year). 1228 CE was a Rat year. However, as part of the text concerns the later reign of Ogedei, logically, those parts were added at a later date, probably in the mid-13th century CE. 1240, 1252, and 1264 CE were all Rat years but if the chronicle were written in the latter two dates then it is strange that Ogedei's death is not covered. Neither was a kurultai held in these years. It is also true that some parts of the pre-Ogedei material seem to be later additions than 1229 CE as there are discrepancies and mistakes in dates, sometimes by as much as 12 years. Finally, there are clear editorial changes, for example, in some spellings to reflect the evolution of the Mongol language, which indicate that the text was edited to some degree after 1229 CE, perhaps as late as the 14th century CE.

Authorship

The author of the Secret History is not known but judging by the scope of the work's content it was clearly written by someone who had access to the inner workings of the Mongol imperial court. One name put forward as a likely candidate is Sigi-quduqu, an adopted son of Genghis Khan. Another possibility is the senior minister Onggud Cingqai, and a third is Tatatonga, the seal-keeper of Genghis Khan. Some scholars have even suggested that the two khans who are the subject of the work had a part in its writing.

Two Surviving Versions

The book today survives in two different versions. The shorter version is written in the Mongol language and was copied into the 16th-century CE Mongolian chronicle Altan Tobci (Nova). In addition, there is a surviving fragment from Tibet of the original Uighur-script version. The second and longer version of the chronicle is written in Chinese and was created as a practice text for Mongol-Chinese translators in Ming Dynasty China (1368-1644 CE). Although the translators of this second version did work with the Mongolian original, there are, nevertheless, a good number of inaccuracies and ambiguities in it, most likely based on misreadings of the original terms. That the translators have made certain interpretations of their own is indicated by some discrepancies when comparing the two versions. The surviving colophon belongs to the longer version.

Content

The longer version of the Secret History has 12 chapters, 282 paragraphs, and is divided into four parts. Part one concerns Mongol legends and, more a poetic saga, contains no dates. Part two is more historical, even if it contains what claim to be direct speeches from the characters involved, and covers the ancestors, rise and reign of Genghis Khan, the founder of the Mongol Empire (1206-1368 CE). Each year is covered in sequence and particular attention is given to how Genghis subdued and made alliances with the many different tribes of the Asian steppe. Part three consists of additional documents relating to the previous part, notably jarliq or imperial orders. Part four deals with the reign of Genghis's son and successor Ogedei Khan up to c. 1240 CE, just before his death in 1241 CE. This final part is written in the same style as part two which suggests it was written by the same person. The shorter version of the Secret History, although seemingly a purer version than the longer Chinese text, is missing some odd paragraphs and the whole of part four. Some scholars have taken this as evidence that the original Secret History ended with the death of Genghis Khan and part four is a later addition, even if added by the original author.

Reliability

The value of the Secret History as a source of history is debated amongst scholars, particularly the earlier parts which have no corroborating external source; such is the problem with ancient texts that are unique. However, it would be unwise to dismiss the Secret History as pure fiction when it deals with subjects for which we have no other information. In addition, the text does contain several negative aspects of Genghis Khan - that he killed his half-brother, for example, and this would seem to at least partially answer any criticism that the Secret History may be a wholly biased portrayal of Mongol superiority, even if it is a very favourable one.

When the text moves on to 12th-century CE affairs it is shown to be, if not in every detail, at least generally reliable by comparing it with Chinese and Persian sources. Finally, as a Mongolian source, the chronicle gives a unique insight into how the Mongols themselves viewed their empire and their own history. The work's preoccupation with Mongol tribal affairs and the importance of conquering China compared to their equally successful campaigns in Western Asia and Eastern Europe are surprisingly different from the coverage of Mongol history in other contemporary sources and, one might also say, in modern textbooks. In Mongolia, the Secret History is today considered one of the most important pieces of the nation's literature and is both studied and memorised in schools.

Extracts

Below are some extracts from the chronicle, taken from the translation by F. W. Cleaves, which, although using outdated English, remains a highly-respected complete translation.

Genghis Khan's mother describes the birth of her son:

When he fiercely issued

From my hot womb,

This one was born holding

A black clot of blood

In his hand.

Even as the Khasar dog

Which bites his own afterbirth;

Even as the panther

Which rushes at the cliff;

Even as the lion

Which is not able to repress his fury;

Even as the python

Which says, 'I shall swallow my prey alive';

Even as the gerfalcon

Which rushes at his own shadow.

(Ch. II, S78)

Genghis Khan on his victory over the Merkid people:

We have made their breasts to become empty.

And we have broken off a piece of their liver.

And we have made their beds to become empty.

And we have made an end of

The men of their descendants.

And we have ravished those of the women of them which remained.

(Ch. III, S113)

Genghis Khan describing with gratitude the work of his personal bodyguard:

My sincere-hearted nightguards

Which, in the snowstorm which is moving,

In the cold which is making one to shiver,

In the rain which is pouring down,

Standing, not taking their rest,

Round about my tent with a frame of lattice,

Have caused my heart to be at peace

Have made me to attain unto the throne of joy.

My trusty nightguards

Which, in the midst of enemies which are making trouble,

Round about my tent with a band of felt

Have, not winking eye,

Stood, staying their assault.

(Ch. IX, S230)

Ogedei Khan describes his improvements to the state messenger network:

We, when the messengers haste, make them to haste, making them to round about the people. And the going of the messengers which run is slow. And it is a suffering for the nation and the people. Now we, determining the matter once and for all, if bringing forth keepers of post stations and keepers of post horses from the diverse thousands of the diverse quarters, establishing seats and seats of post stations, not making them to go round about the people without urgent matters, will it not do?

(Ch. XII, S279)