The Seven Wonders of the Ancient World were seven impressive structures famously listed by ancient writers including Philo of Byzantium, Antipater of Sidon, Diodorus Siculus, Herodotus, Strabo, and Callimachus of Cyrene, among others. The medieval historian Bede, and other medieval writers, also compiled their own lists. The standard list of the seven ancient wonders includes:

- the Great Pyramid of Giza, Egypt

- the Hanging Gardens of Babylon

- the Statue of Zeus at Olympia, Greece

- the Temple of Artemis at Ephesus

- the Mausoleum at Halicarnassus

- the Colossus of Rhodes

- the Lighthouse of Alexandria, Egypt

The Seven Wonders were first defined as themata for Hellenic sightseers (Greek for "things to be seen" which, in today's colloquial English, one would phrase as "must-sees") by Philo of Byzantium (l. 3rd century BCE) in 225 BCE, in his work On the Seven Wonders. Philo and Antipater of Sidon (l. 2nd century BCE) include the walls of Babylon in the list instead of the Lighthouse of Alexandria while Diodorus Siculus (1st century BCE) includes the seven above in his Bibliotheca historica ("Historical Library"). All seven of the wonders were standing at the same time for less than 60 years and, of the seven listed above, only the Great Pyramid exists today.

There is no standard, agreed upon, "authentic" list of the Seven Wonders of the Ancient World. Philo's list is understood to be based on earlier sources and may or may not have been compiled from his own experience. He was an engineer working at the Library of Alexandria, where he wrote his On the Seven Wonders, which was so popular it (or a copy) was brought to Byzantium, copied, and those copies sent to other urban intellectual centers, which is how the list survived up through the time of Bede (l. c. 673-735 CE), by which time all the wonders on the list were long gone except the Great Pyramid. Regarding the origin of the accepted Seven Wonder, scholars John and Elizabeth Romer write:

In common with many other popular images and ideas, the precise origin of this list called the Seven Wonders of the World is now lost to us. References to the Seven Wonders abound in classical writings, yet most of these ancient texts are ambiguous in their authorship, disputed in their dates, and serve only to underline the impression that the Seven Wonders of the World were as well known and, perhaps, as little recited then, as they are now. Securely dated written evidence shows that the first full modern version of the list of Seven Wonders actually appeared less than four centuries ago, in Italy in 1608, and even after that date the seven constituents of the list were not firmly fixed until the arrival of mass printing and popular education in the last century. (ix-x)

Bede's list does not follow the standard but includes others such as the Capitol at Rome and the Theater of Heraclea. Even ancient writers disagreed on what wonders should appear on a list, but it does not seem any would have denied the magnificence of the seven standards recognized today, all of which were raised at sites around the Mediterranean between c. 2560-280 BCE.

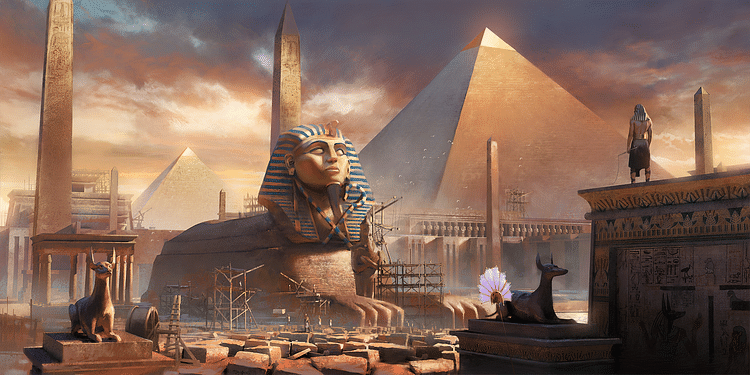

Great Pyramid at Giza

The Great Pyramid at Giza was constructed between 2589 and 2566 BCE during the reign of the Egyptian pharaoh Khufu (known in Greek as 'Cheops') and was the tallest manmade structure in the world for almost 4,000 years. It is thought to have been completed by his successor Khafre c. 2560 BCE at a height of 146 meters (479 ft) with a base of 230 meters (754 ft) using over two million blocks of stone. Excavations of the interior of the pyramid were only initiated in earnest in the late 18th and early 19th centuries, and so the intricacies of the interior which so intrigue modern people were unknown to the ancient writers. It was the structure itself with its perfect symmetry and imposing height which impressed ancient visitors. At the time Diodorus was writing, the pyramid may still have been sheathed, at least partially, with the white limestone facing that made it shine brightly for miles around.

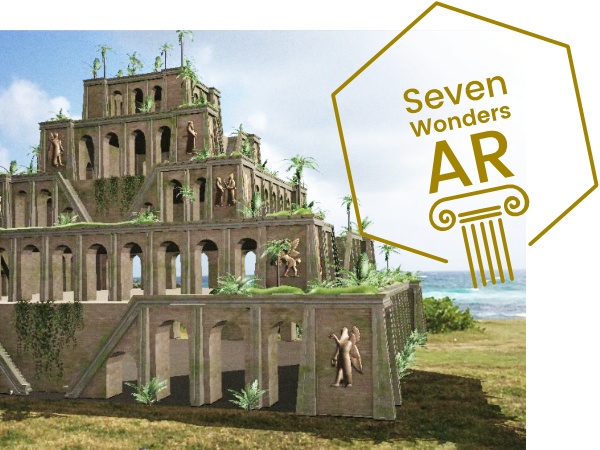

Hanging Gardens of Babylon

The Hanging Gardens of Babylon, if they existed as described, were built by Nebuchadnezzar II between 605-562 BCE as a gift to his wife. They are described by Diodorus Siculus as being self-watering planes of exotic flora and fauna reaching a height of over 23 meters (75 ft) through a series of climbing terraces. Diodorus wrote that Nebuchadnezzar's wife, Amtis of Media, missed the mountains and flowers of her homeland and so the king commanded that a mountain be created for her in Babylon.

The controversy over whether the gardens existed comes from the fact that they are nowhere mentioned in Babylonian history and that Herodotus (l. c. 484-425/413) makes no mention of them in his descriptions of Babylon. There are many other ancient facts, figures, and places Herodotus fails to mention, however, and there is some doubt as to whether he actually visited Babylon. Diodorus, Philo, and the historian Strabo all claim the gardens existed, but it may be they confused Babylon with Nineveh which was famous for its gardens and parks. If the Hanging Gardens did exist, they are said to have been destroyed by an earthquake sometime after the 1st century CE.

Statue of Zeus at Olympia

The Statue of Zeus at Olympia was created by the great Greek sculptor Phidias, known as the finest sculptor of the ancient world in the 5th century BCE (he also contributed to the Parthenon in Athens through the statue of Athena that once stood inside the temple). The statue of Zeus depicted the god Zeus seated on his throne, his skin of ivory and robes of hammered gold, and was 12 meters (40 ft) tall, designed to inspire awe in the worshippers who came to the Temple of Zeus at Olympia. The travel writer and historian Pausanias (l. 110-180 CE) describes the statue, which was regularly referred to as "the god":

The god, made of gold and ivory, sits on a throne. There is a garland on his head made as if of olive shoots. In his right hand he is carrying a Victory [figure], also made of gold and ivory, and this figure is holding a ribbon and has a wreath on its head. In the left hand of the god is a scepter decorated with every kind of precious metal. The bird perched on the scepter is the eagle. The sandals of the god are made of gold too, and so is his robe. Embroidered on the robe are figures of animals and white lilies. The crown is ornate with its gold and jewels, ornate with its ebony and ivory.

(Description of Greece, Book 5: I.xi, 1-2/Romer, 1)

The statue of Olympian Zeus is regularly referenced as breathtaking. Not everyone was awestruck by the great work, however. The geographer and historian Strabo (l. c. 64 BCE to 24 CE) comments:

The greatest of these [statues] was the image of Zeus made by Phidias, son of Charmides, an Athenian, of ivory and so large that – although the temple was also exceedingly large – the craftsman seems to have missed the proper proportions, making him seated but almost touching the ceiling with his head, thus giving the impression that, if he rose up erect, he would unroof the temple.

(Geography, 8.3.30)

The Temple at Olympia fell into ruin after the rise of Christianity and the ban on the Olympic Games as pagan rites. The statue was carried off to Constantinople where it was later destroyed, sometime in either the 5th or 6th centuries, by either fire or an earthquake.

Temple of Artemis at Ephesus

The Temple of Artemis at Ephesus (Ephesos), a Greek colony in Asia Minor, took over 120 years to build and only one night to destroy. Completed in 550 BCE, the temple was about 129 meters (425 ft) long, almost 69 meters (225 ft) wide, supported by 127 about 18-meter (60-foot) high columns. Sponsored by the wealthy King Croesus of Lydia, who spared no expense in anything he did (according to Herodotus, among others) the temple dedicated to the Greek goddess Artemis was so magnificent that every account of it is written with the same tone of awe and each agrees with the other that this was among the most amazing structures ever raised by human beings.

On 21 July 356 BCE, a man named Herostratus set fire to the temple in order, as he said, to achieve lasting fame by forever being associated with the destruction of something so beautiful. The Ephesians decreed that his name should never be recorded nor remembered, but Strabo set it down as a point of interest in the history of the temple. On the same night the temple burned, Alexander the Great was born and, later, offered to rebuild the ruined temple, but the Ephesians refused his generosity. It was rebuilt on a less grand scale after Alexander's death but was destroyed by the invasion of the Goths. Rebuilt again, it was finally destroyed utterly by a Christian mob led by Saint John Chrysostom in 401.

Mausoleum at Halicarnassus

The Mausoleum at Halicarnassus was the tomb of the Persian Satrap Mausolus, built c. 351 BCE. Mausolus chose Halicarnassus (Bodrum in modern-day Turkey) as his capital city, and he and his beloved wife Artemisia went to great lengths to create a city whose beauty would be unmatched in the world. Mausolus died in 353 BCE, and Artemisia wished to create a final resting place worthy of such a great king. Artemisia died two years after Mausolus, and her ashes were entombed with his in the mausoleum. Pliny the Elder (l. 23-79 CE) reports that the craftsmen continued work on the structure after her death, both as a tribute to their patroness and knowing the mausoleum would bring them lasting fame.

The tomb was 41 meters (135 ft) tall and ornately decorated with fine sculpture. It was destroyed by a series of earthquakes and lay in ruin for hundreds of years until, in 1494, it was completely dismantled and used by the Knights of St. John of Malta in the building of their castle at Bodrum (where the ancient stone blocks can still be seen today). The tomb of Mausolus is the origin of the English word mausoleum.

Colossus of Rhodes

The Colossus of Rhodes was a statue of the god Helios (the patron god of the island of Rhodes) constructed between 292 and 280 BCE. It stood over 33 meters (110 ft m) high, overlooking the busy harbor of Rhodes and, despite fanciful depictions to the contrary, stood with its legs together on a base (much like the Statue of Liberty in the harbor off New York City in the United States of America, which is modeled on the Colossus) and did not straddle the harbor.

The statue was commissioned after the defeat of the invading army of Demetrius in 304 BCE. Demetrius left behind much of his siege equipment and weaponry, and this was sold by the Rhodians for 300 talents (approximately 360 million US dollars), which money they used to build the Colossus. The statue stood for only 56 years before it was destroyed by an earthquake in 226 BCE. It lay in impressive ruin for over 800 years, according to Strabo, and was still a tourist attraction. Pliny the Elder claims that the fingers of the Colossus were larger than most statues of his day. According to the historian Theophanes, the bronze ruins were eventually sold to "a Jewish merchant of Edessa" around the year 654, who carried them away on 900 camels to be melted down.

Lighthouse of Alexandria

The Lighthouse at Alexandria, built on the island of Pharos, stood close to 134 meters (440 ft) in height and was commissioned by Ptolemy I Soter. Construction was completed sometime around 280 BCE under the reign of Ptolemy II Philadelphus. The lighthouse was the third tallest human-made structure in the world (after the pyramids), and its light (a mirror that reflected the sun's rays by day and a fire by night) could be seen as far as 35 miles out to sea. The structure rose from a square base to a middle octagonal section up to a circular top and those who saw it in its glory reported that words were inadequate to describe its beauty. The lighthouse was badly damaged in an earthquake in 956, again in 1303 and 1323, and by the year 1480, it was gone. The 15th-century Fort Qaitbey now stands on the site of the lighthouse, built with some of the stones from its ruins.

![Lighthouse of Alexandria [Artist's Impression]](https://www.worldhistory.org/img/r/p/750x750/7615.jpg?v=1722353049)

Conclusion

The Seven Wonders of the Ancient World were, by no means, a comprehensive agreed-upon list of the most impressive structures of the day. Rather, the list was very much like a modern-day tourist pamphlet informing travelers on what to see on their trip. Those masterpieces listed above are the traditionally accepted ancient wonders, as first set down by Diodorus Siculus, but Philo of Byzantium and Antipater of Sidon both left off the Lighthouse of Alexandria, and there were many writers who disagreed on what constituted a "wonder" and what was only of passing interest. Herodotus, for example, cites the Egyptian Labyrinth at Hawara as being far more impressive than even the pyramids of Giza:

I have personally seen it, and it defies description. If someone put together all the strongholds and public monuments of the Greeks, it would be obvious that less labor and money had been expended on them than on this labyrinth - and I say this despite the fact that the temples of Ephesus and Samos are remarkable structures. The pyramids, of course, beggar description and each of them is the equivalent of a number of sizeable Greek edifices, but the labyrinth outstrips even the pyramids.

(Histories, II.148)

Reconstructions of the Seven Wonders of the Ancient World

Nor did all agree on which of the architectural wonders was the most wonderful, as in this passage from Antipater of Sidon, praising the Temple of Artemis:

I have gazed on the walls of impregnable Babylon along which chariots may race, and on the Zeus by the banks of the Alpheus, I have seen the hanging gardens, and the Colossus of the Helios, the great man-made mountains of the lofty pyramids, and the gigantic tomb of Mausolus; but when I saw the sacred house of Artemis, that towers to the clouds, the others were placed in the shade, for the sun himself, has never looked upon its equal, outside Olympus.

(Greek Anthology, IX.58)

As noted, Antipater also replaced the Lighthouse with Babylon's walls, and Callimachus of Cyrene (l. c. 310 to c. 240 BCE), among others, listed the Ishtar Gate of Babylon among the seven wonders. The list of Diodorus Siculus, however, is now accepted as the official definition of the Seven Wonders of the Ancient World. Although different writers chose varied sites to celebrate as "wonders", all the lists and commentaries agree that, once upon a time, humans raised structures that were worthy of the work of the gods and, once seen, were never to be forgotten.