The ancient Egyptians enjoyed storytelling as one of their favorite pastimes. Inscriptions and images, as well as the number of stories produced, give evidence of a long history of the art of the story in Egypt dealing with subjects ranging from the acts of the gods to great adventures to meditations on the meaning of life and magical events.

One of the most interesting collections of stories, often published under the title Tales of Wonder or King Cheops and the Magicians comes from the Westcar Papyrus. These stories, set in the time of king Khufu of the 4th Dynasty of the Old Kingdom (c. 2613-2181 BCE), concern magical and wonderous events which happened in the past, present, and hint at the future.

In the manuscript, each of Khufu's sons speaks in turn, telling their own tale for their father's entertainment, until his son Hardedef claims it would be more interesting to experience a wonder in the present and produces a magician for this purpose. The fifth story then picks up on the conclusion of the fourth tale to tell of the magical birth of the first three kings of the 5th Dynasty. These are some of the most entertaining stories from ancient Egypt and so intricately connected by theme and setting that the scroll is considered by some scholars as more of a novel than a collection of short tales.

History of the Scroll

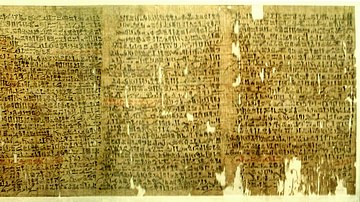

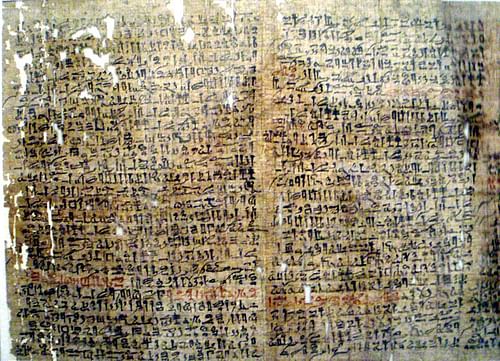

The Westcar Papyrus is a scroll dated to the Second Intermediate Period (1782-c.1570 BCE). It takes its name, as most Egyptian papyri do, from the name of the man who first acquired it, Henry Westcar. Westcar purchased the piece c. 1824 CE, under circumstances which are unknown, while traveling in Egypt. Since he never disclosed how or where he came into possession of the scroll, its provenance is lost; no one knows where it was found or in what context it was originally discovered.

It was either purchased or acquired illegally by the famous Egyptologist Karl Lepsius in c. 1839 CE who was able to read it in part but no real progress was made in understanding what the papyrus contained until it was translated into German by Adolf Erman in 1890 CE. Erman's translation, which calls the stories "fairy tales" set the tone for later translations which fairly consistently mention the magician or "wonder" in their titles.

The scroll originally contained five stories but the first has been lost except for the last lines. It was written in the hieratic script of classical Middle Egyptian and the papyrus dates from the Hyksos period (Lichtheim, 215). As there is evidence of a previous text which was erased, the scroll is designated a palimpsest, a work written on manuscript pages which once held another. Since papyrus scrolls were expensive writing material it was common to scrape off an old document and re-use the papyrus for a new work.

The Context

In this case, at some point in either the late Middle Kingdom (2040-1782 BCE) or the Second Intermediate Period, a scribe removed an earlier work from the scroll to write down a story set in the Old Kingdom. The context of the work makes dating the piece problematic because although the papyrus itself dates to the Second Intermediate Period the stories themselves would make more sense as having been written in the Middle Kingdom.

The Middle Kingdom came after the First Intermediate Period (2181-2040 BCE) in which the central government was weak following the collapse of the Old Kingdom. Middle Kingdom literature, which is among Egypt's finest, consistently hearkens back to the "good old days" of the Old Kingdom and often uses devices, as in The Prophecies of Neferti, of setting a tale in the period of the Old Kingdom where someone makes a "prophecy" concerning future events. The famous Admonitions of Ipuwer is another Middle Kingdom literary work along these same lines which bemoans the horrible state of existence in an Egypt in which the stability of the Old Kingdom has been lost and chaos reigns in the land.

In the Second Intermediate Period, on the other hand, the Egyptian government consisted only of the city of Thebes ruling over a part of the country. The Delta region and part of Lower Egypt was held by the foreign Hyksos and the the southern tier of Upper Egypt was under Nubian control. A work like the Westcar Papyrus fits more neatly with Middle Kingdom literature than Second Intermediate or New Kingdom (c. 1570-1069 BCE) works. Egyptologist William Kelly Simpson claims that the work "appears to belong to Dynasty 12" (13). This would place it, appropriately, squarely in the greatest dynasty of the Middle Kingdom. Egyptologist Verena Lepper also places the piece in the Middle Kingdom but dates it to the 13th Dynasty.

Still, the papyrus is consistently dated to "the Hyksos period", following scholar Miriam Lichtheim's assessment, which places it in the Second Intermediate Period but at which point is unknown. It is possible the work was written during the transition from the Second Intermediate Period to the New Kingdom, when Ahmose I (c. 1570-1544 BCE) was driving the Hyksos from Egypt. This would make sense in that a series of tales surrounding the legendary Khufu and his sons of the Old Kingdom, and ending with a prophecy of great kings to come, would fit with the nationalistic bent of New Kingdom literature.

The Stories

Story No. 1

The first story is missing except for the set piece at the end (which also appears in the next two) where Khufu praises the tale by commanding that sacrifices be made to the kings who are featured in them and those who performed the miracles. The conclusion mentions the king Djoser (c. 2670 BCE) and most likely concerned his brilliant architect and polymath vizier Imhotep (c. 2667-2600 BCE).

Story No. 2

The second story concerns Nebka, a mysterious ruler allegedly from the 3rd Dynasty, and his stay at a priest's house. The priest's wife has an affair with a youth from Nebka's entourage which is discovered by the priest. He then creates a wax crocodile which he gives to the caretaker to drop into the lake where the youth bathes. When this happens, the crocodile comes to life and drags the young man to the bottom. The priest brings Nebka to the lake to see the wonder, calls the crocodile up, and turns it back into a wax figure. Then he tells Nebka what has happened and the king condemns the youth and the wife. The wax crocodile is turned back into a real one and takes the young man while the adulterous wife is burned to death.

Story No. 3

In the third story, king Sneferu is feeling bored and depressed and his chief priest suggests he take a boat ride with the most beautiful women in his harem. They all go out on the lake and Sneferu is enjoying himself when one of the women loses a green fish-shaped jewel from her hair and stops rowing. She refuses Sneferu's offer to replace it and so he calls to the chief priest, who is also on the boat, to do something. The priest parts the waters of the lake, retrieves the jewel, and then closes the waters again. Sneferu is pleased, the women row on, and the priest is rewarded for a wonder which the writer of Exodus would later borrow for his own work.

Story No. 4

The fourth story breaks the pattern when Khufu's son Hardedef complains that all the stories thus far have been about the past even though miracles can happen in the present. He tells the king about a man who can do great magic - such as reattaching a head once it has been severed - and knows many secret things and Khufu sends him to bring the man to court. Hardedef retrieves the sage, Djedi, and when they enter the palace Khufu commands a prisoner be brought and decapitated but Djedi stops him saying how he cannot perform this magic on a human being because it is against the gods' will. He successfully demonstrates his powers on a goose, a waterfowl, and an ox, however. Djedi is then asked a question about the shrines of Thoth and says it is not in his power to deliver the secrets for they must come from the eldest son of Reddedet, a woman who will give birth to the kings of the next dynasty.

Story No. 5

The fifth tale picks up on Djedi's last lines with Reddedet enduring a difficult labor. The god Ra sends Isis, Nephthys, Meskhenet, Heket, and Khnum to help her. They arrive at the house disguised as musicians and dancers and find Reddedet's husband, Rewosre, upset about the labor. He accepts their offer to help and Isis, Nephthys, and Heket deliver the three children. These will be the first three kings of the 5th Dynasty: Userkaf, Sahure, and Kakai. Rewosre is grateful and gives the disguised deities a sack of grain to brew beer with and they leave. Isis then remembers that they have given nothing miraculous to the children or their parents and so the gods create three royal crowns, put them in the sack, and return to the house. They generate a storm as an excuse and ask if they can leave the grain sack so it will not get wet.

The sack is then locked in a room and the gods go on their way. Two weeks later, once Reddedet has recovered, they are preparing a party and her maidservant tells her they have no grain to brew beer with except the sack which Rewosre gave to the musicians. Reddedet says to use it and Rewosre will replace it before they return. When the maidservant goes into the room she hears music and celebration and, frightened, runs and tells Reddedet. Reddedet goes to the room and realizes the sounds are coming from the sack and sees the three royal crowns. She is overjoyed that her sons will be kings but is afraid of Khufu finding out so she has the sack locked away in a chest. A few days later she has a fight with the maidservant who threatens to go tell Khufu the secret but, on her way, she stops to tell her brother what has happened. Her brother becomes enraged that she would threaten the lady of the house in such a way and beats her with a whip. The maidservant runs to the river to get a drink of water and is eaten by a crocodile.

The story, and manuscript, end with the brother going to the house to tell Reddedet what has happened. He finds her upset and asks what is wrong. Reddedet tells him about the maidservant running away to tell Khufu and how she is worried what will happen. The brother tells her not to worry because her secret is safe; his sister was just eaten by a crocodile.

The manuscript seems to break off at this point but Miriam Lichtheim, among other scholars, claims that the scene of the brother comforting Reddedet is the conclusion of the piece. Egyptologist Verena Lepper agrees, noting that there is ample space on the papyrus for a longer conclusion if one had been intended.

Significance

The Westcar Papyrus is considered one of the most important pieces of Egyptian literature because it epitomizes the kinds of tales which were most popular. There are many examples of didactic tales that teach a lesson which are still very entertaining but the stories of the Westcar Papyrus primarily aim at entertaining first. Egyptologist Rosalie David writes:

Unlike other tales intended to educate and inform the upper and middle classes, the style and language of this text indicate that it would have belonged to Egypt's popular tradition, passed on orally by public storytellers traveling from town to town. (212)

Still, as David further notes, the stories did have "political and religious propagandist aims" in highlighting divine intervention in the births of the first three kings of the 5th Dynasty as well as showing Khufu and his sons as "regular people" engaged in an evening of storytelling.

It may seem strange to a modern reader for the scribe to set the story so far in the distant past; for what purpose could be served by reminding people of the divine right of kings long dead? The prophecy of Djedi regarding the kings, however, and then the story of their birth with the help of the three goddesses, would have impressed upon people the interest the divine had in earthly affairs and the importance of monarchs who were approved of by the gods.

The 5th Dynasty had its own problems, after all, with the costs incurred by the monarchs of the 4th Dynasty in building their immense monuments at Giza, exempting the priests from taxation, and paying the clergy for continuous upkeep and the rituals required to honor the souls of the dead. A later period, facing its own problems, could have taken comfort in the knowledge that earlier people had struggled and prevailed and so, too, would they. Whether the Westcar Papyrus was written at a high or low point in the Middle Kingdom or later in the uncertain time of the Second Intermediate Period, that would have been an important, and comforting, concept to those who made up the original audience.