Theophilos was emperor of the Byzantine Empire from 829 to 842 CE. He was the second ruler of the Amorion dynasty founded by his father Michael II. Popular during his reign and responsible for a lavish rebuilding of Constantinople's palaces and fortifications, Theophilos is chiefly remembered today for a major defeat by the Arab Caliphate in 838 CE and as the last emperor who supported the policy of iconoclasm, that is the destruction of icons and their veneration being treated as heresy.

Succession & Popularity

Theophilos was from Amorion, the city in Phrygia which gave its name to the dynasty begun by his father Michael II (r. 820-829 CE). Michael's reign, tarnished right from the beginning by his brutal murder of his predecessor Leo V (r. 813-820 CE), continued its downward spiral with a serious revolt led by Thomas the Slav and significant defeats at the hands of the Arabs in Sicily and Crete.

Inheriting the throne in 829 CE aged 25, Theophilos was seen as a new hope for the empire to get back on its feet again. A return to former glories was not to be but at least Theophilos was popular because of his exuberant personality, even participating once in a chariot race in the Hippodrome of Constantinople (which he won, of course). The emperor also enjoyed a reputation as a lover of learning and justice, especially when he introduced the tradition of the emperor riding to church on Fridays and permitting any commoner to throw questions of justice or appeals his way. The historian J. Herrin recounts one such episode:

On one of the occasions a widow complained to Theophilos that she had been defrauded of a horse by the city eparch. Indeed, she claimed it was the vey horse he was riding! He ordered an investigation and discovered that her story was correct: the eparch had taken her horse and given it to the emperor. Theophilos immediately returned the horse to its rightful owner and had the very high-ranking official punished. (75)

Another eccentricity of the emperor was the habit of walking about the streets of his capital in disguise asking the people what they thought of the problems of the day and checking if the merchants were selling their goods at fair prices. Theophilos' reputation for learning stemmed not only from his own education but his endorsement of everyone else's - he increased the faculties of the university at the capital, increased the number of scriptoria where manuscripts were duplicated, and ensured that teachers were paid by the state.

Building Projects

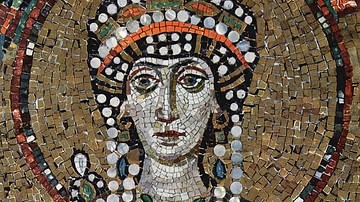

Theophilos' other domestic achievements included a lavish restoration of the royal palace and its gardens, which, over the centuries, had become something of a hotchpotch architectural mess. Buildings were ripped down and new homogenous ones with connecting corridors were built using white marble, fine wall mosaics and columns in rose and porphyry marble. Best of all was the throne room, here described by the historian L. Brownworth:

No other place in the empire - or perhaps the world - dripped so extravagantly in gold or boasted so magnificent a display of wealth. Behind the massive golden throne were trees made of hammered gold and silver, complete with jewel-encrusted mechanical birds that would burst into song at the touch of a lever. Wound around the base of the tree were golden lions and griffins staring menacingly from beside each armrest, looking as if they could spring up at any moment. In what must have been a terrifying experience for unsuspecting ambassadors, the emperor would give a signal and a golden organ would play a deafening tune, the birds would sing, and the lions would twitch their tails and roar. (162)

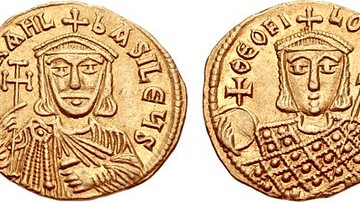

Other projects, all probably funded by the discovery of gold mines in Armenia, included the building of the Bryas summer palace in the capital, adding the bronze doors to the Hagia Sophia which are still there today, extending the city's harbour fortifications, and introducing a new copper follis coin. Theophilos' reputation for extravagant spending was epitomised by the bridal show he organised to find himself a wife. The winner was an Armenian girl named Theodora who received as her prize, besides the emperor himself, of course, a magnificent golden apple just as in the judgement of Paris story from ancient Greece. If ever an emperor knew how to market to his people the good times were here again, it was Theophilos.

Defending the Empire

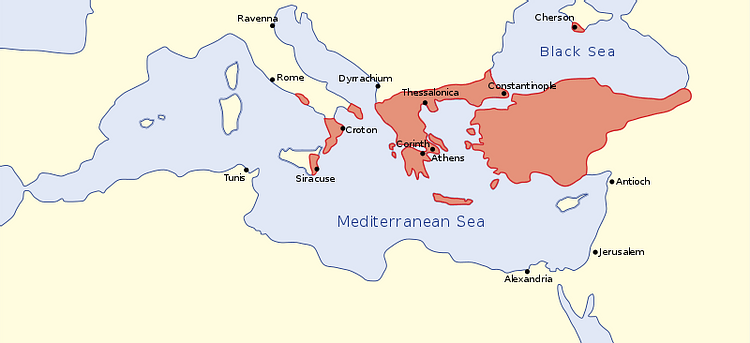

In foreign affairs, Theophilos benefitted from Leo V's defeat of the Bulgars in 814 CE and the sudden death of their leader, the Khan Krum. A 30-year peace allowed both the Bulgars and Byzantines to concentrate on other threats. Theophilos strengthened the empire's defences, notably building the Sarkel fortress at the mouth of the Don River c. 833 CE to protect against invasion from the Rus Vikings who had formed the state of Kiev. In a similar vein, new provinces or themes, were established: Cherson (in the Crimea, and protected by the Sarkel fortress), and Paphlagonia and Chaldia (both intended to better protect the area south of the Black Sea). Smaller military districts (kleisoura) were created at Charsianon, Cappadocia, and Seleukeia in central and southeast Asia Minor to protect the mountain passes most likely to be used by invading armies.

Elsewhere, although in the East the Arab Caliphate had previously been kept quiet by its own internal problems, the Byzantines lost the initiative to the western Arabs in Italy when Taranto fell in 839 CE, splitting the Byzantine territory there in two. Theophilos concentrated on meeting the Arab threat closer to home in Asia Minor and he made inroads into Cilicia in 830 and 831 CE for which he awarded himself a triumph. Relations were not always hostile between the two states as during the middle part of his reign the emperor twice sent the learned clergyman John VII Grammatikos on diplomatic missions to the Arabs from which he brought back new scientific knowledge and ideas which influenced Byzantine art and architecture.

Caliph Mutasim (r. 833-842 CE) was ambitious, though, and he sent a huge army into Byzantine territory in 838 CE. Despite having the two gifted generals of Theophobos and Manuel, the Byzantines were unable to prevent defeat at the battle of Dazimon in Pontos (northern Asia Minor) on 22 July 838 CE. The victorious Arab army, led by the Caliph's own star general Afshin, were then able to sack and take the strategically important cities of Ankara and Amorion. The acquisition of Amorion - the emperor's hometown - was sweet revenge for Mutasim, whose father's city of Zapetra had been sacked by Theophilos only the year before. This fact may also explain the Caliph's forced relocation of the entire civilian population and infamous execution of the so-called 42 Martyrs of Amorion who had all refused to convert to Islam after seven years of imprisonment.

Iconoclasm

The emperor's domestic affairs were largely focussed on the battle within the church on whether or not the veneration of icons was acceptable or not as orthodox practice. Leo V had begun a second wave of iconoclasm in the Byzantine Church (the first having occurred between 726 and 787 CE), whereby all prominent religious icons were destroyed and those who venerated them were persecuted as heretics. After a lull during the reign of Leo's successor Michael II, Theophilos picked up the pace again and vehemently attacked the iconophiles. In this campaign he was aided by the staunch iconoclast John VII Grammatikos who had served under Leo V and who was made Patriarch (Bishop) of Constantinople c. 837 CE. A major force behind the iconoclasm policies of Leo V, the fact that John was Theophilos' tutor and advisor, perhaps unsurprisingly, led to a new wave of attacks on icons and their supporters.

Important figures who suffered for their pro-icon beliefs included the brothers Theodore and Theophanes Graptos and the icon-painter Lazaros. The Graptos brothers acquired their name after both had their foreheads branded (graptos). Theophilos ordered that twelve iambic pentameters were to be tattooed on the pair as a warning to all of the dangers of superstition and disobeying the law. Lazaros' punishment was different but no less painful, as he was flogged and had his hands burned with red-hot nails. The painter was permitted to leave Constantinople, though, and he sought refuge in the Phoberou Monastery at the north end of the Bosphorus.

Theophilos might have been good at bending the clergy to his way of thinking but closer to home he was rather less successful. The emperor's consort Theodora remained a regular venerator of icons in secret, even inside the royal palace. After Theophilos' death, John VII Grammatikos was exiled in 843 CE and in March of the same year Theodora swiftly ended iconoclasm in a move widely known as the “Restoration of Orthodoxy' or even the “Triumph of Orthodoxy”, which was celebrated in a new outbursting of religious art.

Death & Successors

When Theophilos, aged 38, died of dysentery in January 842 CE he was succeeded by his son Michael III but as he was still a minor Theodora ruled as his regent until 855 CE. Besides ending iconoclasm, for which she was later made a saint, she also ensured that her husband's memory was not condemned by the Church, successfully persuading the bishops that Theophilos had repented of his iconoclastic zeal on his deathbed. Theophilos gained literary immortality as he is one of the judges in hell in the famous mid-12th century CE satire Timarion - illustrating the emperor's reputation for justice was long-lasting indeed. His son Michael would be the last ruler of the Amorion dynasty as he unwisely befriended and promoted Basil the Armenian who killed his sponsor and took the throne for himself in 867 CE as Basil I, founding the enduring Macedonian dynasty.