The Third Intermediate Period (c. 1069-525 BCE) is the era following the New Kingdom of Egypt (c. 1570-c.1069 BCE) and preceding the Late Period (c.525-332 BCE). Egyptian history was divided into eras of 'kingdoms' and 'intermediate periods' by Egyptologists of the late 19th century CE to clarify the country's history, but were not used by the ancient Egyptians themselves.

The term 'kingdom' is used to define an era of strong central government while 'intermediate period' designates a time of disunity and divided rule. In the First Intermediate Period of Egypt (2181-2040 BCE) and the Second Intermediate Period (c. 1782-1570 BCE) this division caused tension between the two seats of power. In the First Intermediate Period relations were strained between the two kingdoms of Herakleopolis and Thebes, and during the Second Intermediate Period of Egypt between Thebes and the Hyksos rulers of Avaris, to the north, and the Nubians to the south.

THE Division of Power

In the Third Intermediate Period of Egypt, power was held almost equally between Tanis and Thebes early on, fluctuating at times one way or another, and the two cities ruled jointly even though they often had quite different agendas. Tanis was the seat of secular rule while Thebes was a theocracy. As there was no separation between one's religious and daily life in ancient Egypt, 'secular' should be understood here along the lines of 'pragmatic.' The rulers of Tanis made their decisions based upon circumstances and accepted the responsibility even though the gods were certainly consulted. The High Priests at Thebes consulted the god Amun directly on every aspect of rule, and, in fact, Amun could safely be considered the actual 'king' of Thebes.

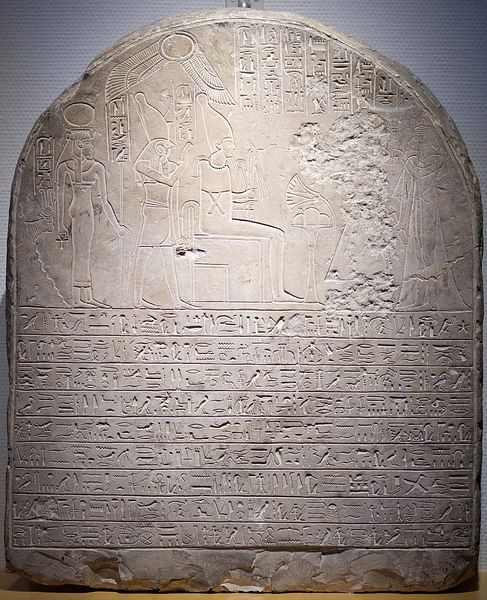

The king of Tanis and the High Priest of Thebes were often related as were those of the two ruling houses. The position of God's Wife of Amun, a position of great power and wealth, illustrates this clearly as both daughters of the rulers of Tanis and Thebes held it. Joint projects and policies were undertaken by both cities, as evidenced by inscriptions left by the kings and priests, and each understood and respected the legitimacy of the other.

With this in mind, it is important to note that the Third Intermediate Period has long been regarded as a kind of epilogue to Egyptian history and an even darker age of chaos and collapse than the earlier intermediate periods. None of the intermediate periods of Egypt were as chaotic as early Egyptologists (and even later ones) interpreted them. The views of these early scholars were very much influenced by their times and the form of government they recognized as legitimate. Strong central rule was interpreted as good while disunity was seen as perilous. In reality, all three of the intermediate periods maintained a continuity of culture without a unifying central government and each added their own contributions to Egypt's history.

The difference between the first two and the last is that, following the Third Intermediate Period, Egypt did not rise again to continue on to greater heights. In the latter part of the 22nd Dynasty, Egypt was divided by civil war, and by the time of the 23rd, the country was divided between self-styled monarchs who ruled from Herakleopolis, Tanis, Hermopolis, Thebes, Memphis, and Sais. This division made a united defense of the country impossible and the Nubians invaded from the south.

The 24th and 25th dynasties saw unification under Nubian rule, but the country was not strong enough to resist the advance of the Assyrians first under Esarhaddon (681-669 BCE) in 671/670 BCE and then by Ashurbanipal (668-627 BCE) in 666 BCE. Although the Assyrians were driven from the country, Egypt did not have the resources to repel other invaders. The Persian invasion of 525 BCE ended Egyptian autonomy until the rise of the 28th Dynasty of Amyrtaeus (c.404-398 BCE) in the Late Period freed Lower Egypt from Persian domination.

Amyrtaeus, however, did not unify the country under Egyptian rule and the Persians continued to hold Upper Egypt. The 30th Dynasty (c. 380-343 BCE), also of the Late Period of Egypt, did achieve unity but it did not last long and the Persians returned in 343 BCE to hold Egypt as a satrapy until it was taken by Alexander the Great in 331 BCE. This period, therefore, is generally seen as a long decline which extinguished Egyptian culture, and while that interpretation is understandable, it is not quite accurate.

The Nature of the Third Intermediate Period

This difference between the Third Intermediate Period and the first two has resulted in a number of scholars, from the 19th through the 20th centuries CE and even to the present, characterizing the era as the end of Egyptian history and the collapse of the culture. The previous two intermediate periods have also been presented as 'dark ages' of confusion and chaos, but the Third Intermediate Period receives the worst treatment because there was no glorious Middle Kingdom or New Kingdom which followed it, only the Late Period which is often seen as simply a continuation of the Third Intermediate Period's decline. These interpretations do a great disservice to an era which, although lacking in the traditional unity and homogeneity of the earlier periods, still maintained a strong sense of culture.

Egyptian mortuary rites, which resulted in some of the most impressive works of art for upper class and royal tombs, continued to be observed. Artwork of striking detail and innovation, especially in bronze, faience, silver, and gold, was produced during this time as well as intricate inscriptions, paintings, and statuary. Building projects were minimal during this time both in number and scope because the resources and a central government able to organize large-scale projects were not available until the reign of Amasis (Ahmose II, 570-526 BCE) of the 26th Dynasty and then the later unification of the country under the 30th Dynasty.

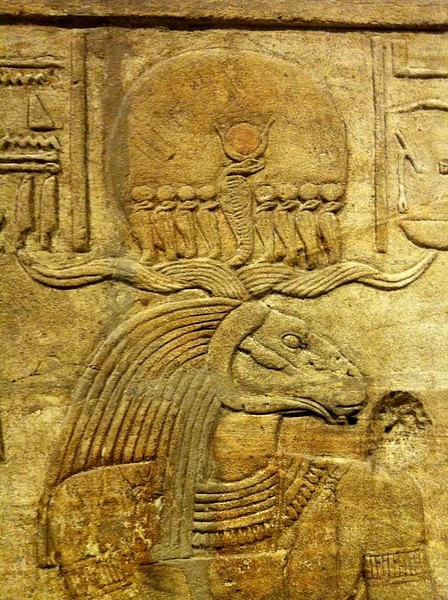

Religious practices seem to have focused on the concept of the pharaoh as a son of god, which led to the development of the mammisi (birth house), a local temple dedicated to worship of the child god born of the union of two powerful deities, one of whom was usually associated with the sun. The concept of triads of gods (father, mother, child) had a long history in Egypt and continued during this time with the popularity of the Cult of Isis and the triad of Osiris, Isis, and the child-god Horus. Worship of Amun, especially at Thebes, continued, but the Cult of Isis would outlast Amun's worship and later travel to Rome to influence the early faith of Christianity.

The Third Intermediate Period began as the reign of Ramesses XI (1107-1077 BCE), the last pharaoh of the New Kingdom, came to an end. The power of the great New Kingdom pharaohs had been waning throughout the 20th Dynasty (c. 1190-1077 BCE) while that of the High Priests of Amun had grown. By the end of the New Kingdom, the god Amun was effectively the ruler of Egypt as the pharaoh was no longer considered a necessary intermediary between the people and their gods.

The cult of Amun, based in their great and ever-expanding temple of Karnak at Thebes, owned more land and had more wealth than the crown and their influence had become considerable. Instead of the pharaoh interpreting the will of the gods, the priests consulted Amun himself and the god would answer them. Civic and criminals cases, matters of policy, domestic issues were all decided by the god. Historian Marc van de Mieroop writes:

The god made decisions of state in actual practice. A regular Festival of the Divine Audience took place at Karnak when the god's statue communicated through oracles, by nodding assent when he agreed. Divine oracles had become important in the 18th Dynasty; in the Third Intermediate Period they formed the basis of governmental practice. (266)

When Ramesses XI died he was buried by Smendes (c.1077-1051 BCE), a governor of Lower Egypt who ruled from Tanis and may have been married to a member of the royal family. In keeping with Egyptian tradition, a king was buried by his successor and Smendes claimed the legitimate right to rule and moved the capital from the city of Per Ramesses to Tanis. By this time, however, the priests at Thebes were powerful enough to be able to claim their own legitimacy to govern and the country divided between rule of Lower Egypt from Tanis and that of Upper Egypt from Thebes. Contrary to earlier interpretations of the period, however, this division did not result in civil war or internal strife. Egyptologist John Taylor notes:

It is true that the period was marked by tensions over control of territory and resources, leading on occasion to conflicts, but violence was not endemic; the period as a whole was stable and represents far more than a temporary lapse from traditional pharonic rule. (Shaw, 324)

Smendes founded the 21st Dynasty, and, although it was never as powerful as earlier periods, it maintained the culture and eventually broadened and deepened it as Libyans (known as Meshwesh or the Ma) came to rule and foreign customs became integrated into Egyptian culture. In the 21st Dynasty one finds a number of rulers with Egyptian names who still were most likely Libyan, and in the latter dynasties, Libyans reigned from both Tanis and Thebes under Libyan names, attesting to the acceptance of non-Egyptians in positions of power; a situation which would have been intolerable in Egypt's earlier history. Far from a strife-torn era, the early part of the Third Intermediate Period was one of remarkable tolerance and cooperation. Van de Mieroop writes:

Kings of Tanis and high priests at Thebes recognized each other's existence without rancor. They regularly helped each other and acted jointly. For example, King Smendes sent assistance to Thebes when a flood threatened Luxor temple, and High Priest Pinudjem I helped King Psusennes I when he built the Amun temple at Tanis. The two left joint inscriptions. The relationship between the two houses was very personal. The founder of the dynasty, Smendes, may have been the son of High Priest Herihor, and his daughter married High Priest Pinudjem I...They coexisted under an agreement that can be likened to the concordat between church and state in European history: secular and religious powers accepted each other's areas of influence. In 21st-dynasty Egypt the northern royal house nominally ruled the entire country, but in reality allowed another branch of the family to run the south on the basis of its priestly office. (270)

This division of rule worked well in that the kings of Tanis were able to govern Lower Egypt and the priests of Thebes Upper Egypt with greater attention to detail than a central government at Memphis or Per Ramesses or Thebes administering the welfare of the entire country. Even so, without a strong central government to set a standard every region of Egypt would adhere to, the different administrative districts of the country took what power they could and prospered or suffered want accordingly. Even though Smendes was the legitimate king of Egypt, his actual reach never extended very far beyond Tanis.

Tanis & Thebes

Tanis may have been a small village or city during the New Kingdom which grew as a trade center and point of access to the Nile during the latter years of that era. Although Smendes ruled from the city, its early history is unclear as no archaeological evidence found there predates the reign of Psusennes I (c. 1047-1001 BCE), the third king of the 21st Dynasty. It was most likely built by Smendes from the ruins of Per Ramesses. The early Egyptologists who discovered the city thought it was built by Ramesses II (1279-1213 BCE) because of the number of his inscriptions on the foundation stones. More recent scholarship has shown that these stones were originally part of the metropolis of Per Ramesses which were reused at Tanis.

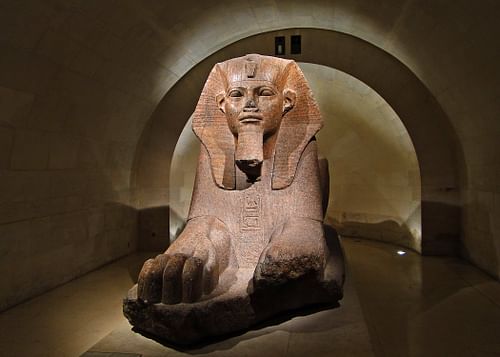

As a new city, Tanis patterned itself on one of the greatest in Egypt's history: Thebes. From the Temple of Amun to the streets and districts, the new city in Lower Egypt mirrored the much older one to the south. The kings of Tanis did the same and took on the traditional titles, fashions, and responsibilities of the pharaohs of earlier times when Thebes had been the capital.

Thebes was already an established and populous city by c. 3200 BCE, had been the capital of the country during the New Kingdom, and was the site of the most massive and important religious center in the country: the Temple of Amun at Karnak. The priests of Amun at Thebes certainly had the power and precedent to declare themselves the 'true kings' of Egypt from the old city and crush the 'pretenders' at Tanis - but they never did. Further, there is no evidence they considered the Tanite kings anything but rightful rulers. Inscriptions make clear that the officials at Thebes considered the kings of Tanis the legitimate monarchs of Egypt while acknowledging their high priests as well.

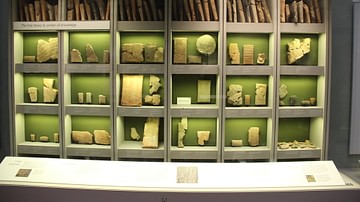

The dynasties of the Third Intermediate Period reflect this division of power in that, besides the 3rd-century BCE historian Manetho's, there are no official king's lists as there are for other periods of Egyptian history. Taylor notes how "a sound historical framework for these centuries has proved more difficult to establish than for any other major period of Egyptian history" because of the lack of a king's list or any other significant documentation Egyptologists usually rely on (Shaw, 324). The king's list of Manetho is more muddled for this period than the others as well resulting in a confusing chronology of rule with ebbs and flows of power fluctuating between the High Priests of Amun at Thebes and the kings of Tanis and, later, other seats of power. Van de Mieroop writes:

Compared to the New kingdom and especially the Ramessid Period, the source material for the Third Intermediate Period is limited. This is true for all levels of society. The village of Deir el-Medina ceased to produce the abundant documents of daily life, and only dispersed finds illustrate how people outside temples and palaces lived during this time. (261)

Van de Mieroop, however, notes that the scarcity of records from this time may be due, in part at least, to them being stored at Tanis and other cities in the marshy Delta region of Egypt "where more humid conditions caused the decay of many remains" (261). This is speculation, however, as few records have been found in the Delta region. Official records would have traditionally been kept at the nation's capital, but as there were essentially two capitals, it is unclear why they would have been kept at Tanis and not Thebes which already had buildings that had served that purpose in the past and where the climate was drier.

Whatever the reasoning was, the result is the loss of a tremendous amount of information on the era and the attendant difficulty of reconstructing it as completely as others. Some notable kings stand out from obscurity and some impressive women also emerge in the position of God's Wife of Amun but the steady chronology of past periods is not possible for this one.

The 21st Dynasty

Smendes founded the 21st Dynasty but was clearly important enough before the death of Ramesses XI to warrant mention. In The Tale of Wenamun (also known as The Report of Wenamun), possibly dating from the late New Kingdom, a government official from Thebes named Wenamun visits Smendes at Tanis on his way to Byblos while no mention is made of Ramesses XI or the court at Per Ramesses at all.

The Tale of Wenamun was once considered an actual historical document, but recent scholarship interprets it as historical fiction. Either way, the story presents a number of interesting aspects about Egypt in the late New Kingdom/early Third Intermediate Period: nomarchs like Smendes were more important than the pharaoh, a simple expedition to retrieve lumber for shipbuilding was a major undertaking, when in the New Kingdom, it would have been so easy as to not even receive mention and the prestige Egypt had once enjoyed among its neighbors had fallen considerably.

Smendes may have been powerful enough to make note of but only had control of Lower Egypt and not even very much of that. He ruled at about the same time as the High Priest Herihor at Thebes, who reigned c.1080-1074 BCE. Herihor had been a general of the army - as all the high priests of Amun were - but also had little influence outside of the city of Thebes. This would be the paradigm for most of the Third Intermediate Period. Like the First Intermediate Period, the individual nomarchs were empowered at the expense of either aspect of the central government and both Tanis and Thebes failed to exert any significant influence over the country as a whole.

The kings of the 21st Dynasty were most likely Libyans ruling under Egyptian names as were the priests at Thebes. Perhaps owing to the Libyan paradigm of small, centralized kingdoms, they were content with their spheres of influence or, perhaps, they actually believed they were co-ruling over a united Egypt. In reality, though, Egypt had been steadily dividing into regional rule throughout the latter part of the Ramessid Period of the New Kingdom. Throughout the course of this era, the country would unify under a strong leader only to fall apart again.

Shoshenq I and the 22nd Dynasty

The 22nd Dynasty was also Libyan, whose kings now ruled openly under Libyan names. It was founded by Shoshenq I (943-922 BCE), who unified Egypt and embarked on military campaigns reminiscent of the days of Egypt's empire. He is thought to be the Shishak from the Bible who sacked Jerusalem and carried away the treasure from Solomon's Temple as described in I Kings 11:40, I Kings 14:25-26, and II Chronicles 12:2-9, although this claim has been challenged. Shoshenq I left an inscription of his campaign into Judah and Israel at Karnak which supports the biblical connection, but it does not mention Jerusalem among the cities sacked. To some scholars, this omission suggests that Shoshenq I is not the biblical Shishak, although every other aspect of the inscription would support the claim he is.

Shoshenq I reformed the government at Tanis and the priesthood at Thebes. The priesthood would no longer be a hereditary position, but one of appointment by the king; and this would also hold true for the selection of God's Wife of Amun. His military campaigns revitalized the economy of Egypt and, under his reign, the country began to somewhat resemble the Egypt of the New Kingdom.

His successes, however, did not last long after his death. Between 922 and 872 BCE, the rulers who followed him sought only to capitalize on his achievements while adding little to them. Owing to the missing and confused records of the time it is difficult to even know for certain the order of succession, but archaeological evidence supports the view that little of note was accomplished.

In 872 BCE Osorkon II (872-837 BCE) took the throne and held the country together, but following his reign Egypt splintered into separate kingdoms ruling from Herakleopolis, Tanis, Sais, Memphis, and Hermopolis in Lower Egypt, and Thebes in Upper Egypt.

The 24th & 25th Dynasties

To the south, the Kushite king Kashta (c. 750 BCE) recognized Egypt's weakness and moved to capitalize on it. Kashta greatly admired Egyptian culture and had 'Egyptianized' his capital city of Napata and, by extension, his realm. He had strong ties through trade with Thebes and was aware of the process by which priests and other high officials were appointed. With no central rule from Lower Egypt able to exert any authority in Upper Egypt, Kashta had his daughter, Amenirdis I, appointed God's Wife of Amun.

The significance of this position was immense, as Van de Mieroop notes: "The political importance of these women was very great and publicly acknowledged. They often acted as regents for their fathers or brothers in the Theban area, adopting royal attributes there" (275). Amenirdis I effectively took control of Thebes and, with it, Upper Egypt. With Lower Egypt divided, Kashta peacefully took control of the country and declared himself King of Upper and Lower Egypt.

His son, Piye (747-721 BCE), strengthened Nubian control of Upper Egypt and, when the kings of Lower Egypt objected, he led his considerable army against them. Piye conquered Lower Egypt, taking all the major cities and subjugating them, and then marched back home to Napata. Egypt was technically now under his reign, but he left the kings of Lower Egypt to regroup and re-establish their authority.

Piye's brother, Shabaka (721-707 BCE) succeeded him and conquered Lower Egypt all the way up to the city of Sais. Egypt was now under Nubian domination, but contrary to earlier interpretations of this period, Egyptian culture and traditions continued to be observed. Shabaka, like Kashta and Piye before him, admired Egypt's long civilization and sought to preserve it. His son, with the very Egyptian name of Haremakhet, was appointed High Priest of Amun at Thebes, and his reign is characterized by building projects throughout Egypt, preservation of historical documents, and securing the borders against invasion.

Shabaka was succeeded by Shebitku (707-690 BCE), a younger brother or nephew, who chose the Egyptian throne name Djedkare. Shebitku inherited a strong country but also a formidable adversary in the form of the Assyrians. When Shoshenq I conquered Judah and Israel it was considered a great achievement by the Egyptians but, long term, it weakened the country by removing an important buffer zone.

Following the Second Intermediate Period, the pharaohs of the New Kingdom initiated a policy of expansion to prevent any future incursions such as that of the Hyksos. During the Third Intermediate Period, these buffer zones shrank and Egypt lost its former power, but there were still nations on its border, such as Judah and Israel, which would serve the same purpose. Shoshenq I's conquest of those regions brought Egypt's border up against that of the Assyrians with no buffer in between.

Under Shabaka's reign, sanctuary had been given to the rebel Ashdod, who had revolted against the Assyrian king Sargon II (722-705 BCE), and under Shebitku, Egypt supported Judah against Sargon II's successor Sennacherib (705-681 BCE). Sennacherib was assassinated before he could mount a campaign against Egypt, but this was carried out by his son Esarhaddon, who invaded in 671 BCE under the reign of the Nubian king Taharqa (c. 690-671 BCE) who is equated with the biblical king Tirhakah from II Kings 19:9 (though this claim is contested). Esarhaddon captured Taharqa's family and a number of other nobles and sent them in chains back to Nineveh, though Taharqa managed to escape. He was succeeded by Tantamani (c. 669-666 BCE), who took Egypt back from the Assyrians and incurred the wrath of Eharhaddon's son and successor Ashurbanipal, who conquered Egypt in 666 BCE.

The 26th Dynasty (Saite Period) & Persian Invasion

The Assyrians were not interested in occupying Egypt, however, and left it under the reign of Necho I (c. 666 BCE), who had become their puppet king. Necho I was killed in Tantamani's campaign to free Egypt from the Assyrians and rule passed to Necho's son Psammeticus I (also known as Psamtik I, c. 665-610 BCE). Psammeticus I is considered the founder of the 26th Dynasty and initiated the so-called Saite Period of Egyptian history during which the kings ruled from the city of Sais in the northern Delta.

Psammeticus I seemingly abided by Assyrian policies but was actually carefully planning their overthrow. C. 656 BCE he launched a naval assault on Thebes and forced the sitting God's Wife of Amun to favor his daughter Nitocris I as successor. Nitocris I assumed the position of God's Wife of Amun and controlled Thebes while Psammeticus I campaigned against the local officials and governors who maintained Assyrian policies.

After freeing Egypt from Assyrian rule, Psammeticus reformed the government at Sais and initiated building projects in keeping with royal tradition. According to some scholars, the Third Intermediate Period ends here with Psammeticus I uniting Egypt, but this interpretation does not make sense. The 26th Dynasty would follow Psammeticus' lead and maintain his policies and vision and a more comprehensive view of the era places the end of the period where it belongs: at the close of the Saite period.

Psammeticus I was a strong leader who impressed upon his subjects the glory of Egypt's past by restoring it through his monumental projects, renovations, restorations, and military achievements. His son, Necho II (610-595 BCE) built upon his father's accomplishments by leading military campaigns, commissioning building projects, and expanding the military. The Egyptians were never a great seafaring people, and recognizing this, Necho II created a navy using Greek mercenaries, which proved quite effective. Necho II is routinely depicted as a great warrior and military leader who strengthened the country he had inherited. In the Bible, he is known as the Egyptian king who kills Josiah of Judah at the Battle of Meggido (II Kings 23:29, II Chronicles 35: 20-22) and, there too, he is seen as an impressive leader.

Necho II was succeeded by his son Psammeticus II (Psamtik II, 595-589 BCE) who continued his father's policies. He was also a great military leader, who is responsible for the Nubians shifting their capital from Napata further south to Meroe c. 592 BCE to distance themselves from Egypt's border. Psammeticus II led a force against the Kingdom of Kush in Nubia, destroying everything in his path, but having won every engagement, he seems to have lost interest in the campaign and returned to Egypt.

Much of his success in this campaign was due to his general, the future Amasis II, who may have resented the incomplete and ultimately futile endeavor. Psammeticus II seems to have been more interested in erasing the names of Kushite rulers from monuments in the south, destroying other buildings, and even possibly trying to erase his own father's name from history. His reasons for doing such things are still debated with no clear answer given.

When Psammeticus II died, he was succeeded by his son Wahibre Haaibre (better known as Apries, 589-570 BCE), whose reign amounted to a series of challenges to his authority. He first unsuccessfully battled the Babylonians and then, when the general Amasis orchestrated a coup, sought their help to win back the throne. He is thought to have been killed by Amasis in battle. Amasis II (also known as Ahmose II) then became pharaoh and elevated the country to a height it had not known in centuries.

Amasis II was a brilliant military leader and bureaucrat who was able to reform government spending while also stimulating the economy and orchestrating military campaigns. Egypt united behind his rule and prospered again with a booming economy, secure borders, and prosperous trade. Building projects, monuments, and other artwork were completed and Egypt's name recovered some of its lost prestige. He was succeeded by his son Psammeticus III (Psamtik III, 526-525 BCE) who was a young man and inexperienced when he came to the throne and poorly equipped for the challenges he had to meet.

According to Herodotus, the Persian king Cambyses II had sent to Amasis asking for one of his daughters as a wife, but Amasis, not wishing to comply but also hoping to avoid conflict, sent the daughter of Apries instead. This former princess of Egypt was deeply insulted by Amasis' decision and especially so since it had long been Egyptian policy to refuse to send noble women to foreign kings as wives. When she arrived at Cambyses II's court, she revealed to him who she really was and Cambyses II swore to avenge the insult of Amasis in sending him a 'fake wife.'

The Persian army mobilized and marched on Egypt. The entry point would be the city of Pelusium in the Delta, and the walls were quickly fortified. Cambyses II's forces struck and were driven back until he formulated a new plan. Knowing of the Egyptian love for animals - cats in particular - Cambyses II had his soldiers round up all the stray and wild animals they could find and had them paint the image of Bastet, the popular Egyptian goddess of cats, on their shields. The Persians then drove the animals before them against Pelusium's walls, and the Egyptians, afraid of hurting the animals or enraging their goddess, surrendered.

Cambyses II is said to have ordered a triumphal march on the spot during which he hurled cats from a bag into the Egyptian's faces in contempt. He took Psammeticus III, the royal family, and thousands of others back to his capital at Susa where most were then killed. Psammeticus III lived as a member of the Persian king's retinue until he was discovered to be fomenting revolt and was executed.

With his death, the 26th Dynasty - and the Third Intermediate Period - came to an end. Persians would rule Egypt in the 27th and 31st dynasties and be a constant threat in the 28th-30th dynastic periods. After the Battle of Pelusium, except for brief periods, Egypt ceased to be an autonomous nation. The Persians held it sporadically until the coming of Alexander the Great in 331 BCE, and after his death, the country was ruled by the Greek dynasty of the Ptolemies until annexed by Rome in 30 BCE.