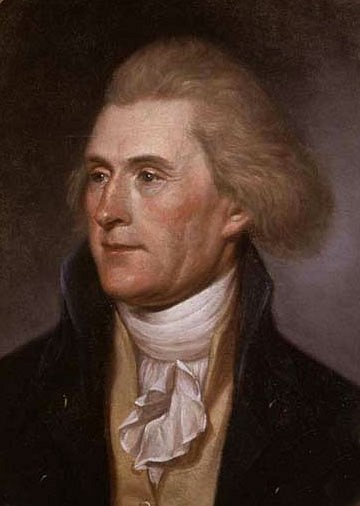

Thomas Jefferson (1743-1826) was an American lawyer, statesman, philosopher, and a Founding Father of the United States. A prominent figure of the American Revolution, he wrote the Declaration of Independence and later served as the first secretary of state, the second vice president, and the third president of the United States (served 1801-1809).

Early Life

Thomas Jefferson was born on 13 April 1743 at Shadwell Plantation in Albemarle County, Virginia. He was the third of ten children born to Peter Jefferson, a wealthy planter and land surveyor, and Jane Randolph Jefferson, a daughter of one of Virginia's most influential families. When Peter Jefferson died in 1757, 14-year-old Thomas inherited 5,000 acres of land as well as 60 enslaved people. From 1758 to 1760, he was privately tutored by Reverend James Maury before going on to the colonial capital of Williamsburg to attend the College of William & Mary. In his first year at college, he spent lavishly on parties, horses, and clothing, but he would soon regret this "showy style of living" (Boles, 18). His second year, therefore, was much more studious; he would apparently spend 15 hours a day at his studies, pausing only to exercise or to practice his violin.

The studious Jefferson soon became the protégé of mathematics professor William Small, who he would fondly remember as "the first truly enlightened or scientific man" he had ever met (Boles, 17). Small introduced Jefferson to the two other great intellectuals in Williamsburg – law professor George Wythe and Lt. Governor Francis Fauquier – and, at their weekly dinner parties, the four men would discuss politics and philosophy, greatly influencing the young Jefferson's political and intellectual development.

After completing his formal studies in 1762, Jefferson remained in Williamsburg to study law under Wythe and was admitted to the Virginia bar five years later in 1767. In 1768, he was elected to the House of Burgesses, representing Albemarle County. That same year, he began construction of a new home atop an 868-foot-high (265 m) mountain that overlooked his plantation. Called Monticello – Italian for "little mountain" – the house became the passion of Jefferson's life, and he would spend the next several decades designing and renovating it. The actual labor, of course, was mostly performed by his slaves; over the course of his lifetime, Jefferson owned approximately 600 enslaved people, most of whom were born into slavery on his property.

In 1772, after several failed romantic pursuits, Jefferson was finally married to the beautiful young widow Martha Wayles Skelton. Five years his junior, Martha shared his passions for literature and music; indeed, they often played music together – she on the harpsichord, he on the violin. The couple would have six children, only two of whom – Martha 'Patsy' (1772-1836) and Mary 'Polly' (1778-1804) – would survive to adulthood. When Jefferson's father-in-law died in 1773, he and Martha inherited 11,000 acres of land and 135 more enslaved people. By then, Jefferson had become involved with Virginia's struggle against Great Britain. Parliament's attempts to tax the colonists without their consent were vehemently opposed by the American Patriots, who saw such taxes as violations of their 'rights as Englishmen'. In 1774, Jefferson argued as much in his A Summary View of the Rights of British America. In it, he asserted that the colonies had the right to govern themselves, that they were tied to the English king only through voluntary bonds and that Parliament had no right to interfere in their affairs. This work earned him recognition as a Patriot leader in Virginia and led to his appointment as a delegate to the Second Continental Congress in Philadelphia in the spring of 1775.

Revolution

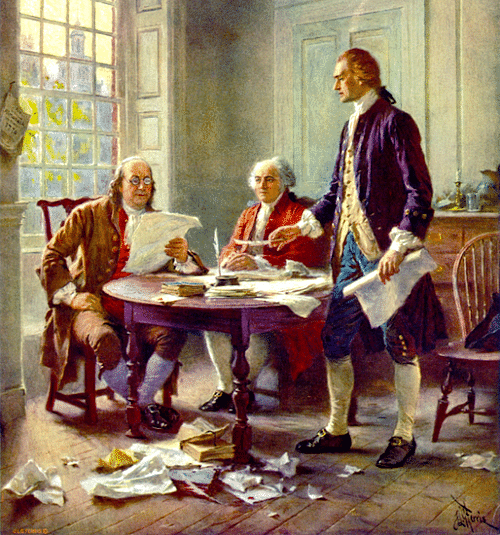

Jefferson was among the youngest and least distinguished members of Congress, and his inherent shyness prevented him from speaking much during the first months of discussions. Yet when it came time for Congress to vote on the prospect of declaring independence from Great Britain in June 1776, Jefferson was assigned to the so-called Committee of Five and tasked with drafting a statement justifying such a separation. The committee included the eminent statesmen John Adams, Benjamin Franklin, Robert R. Livingston, and Roger Sherman, but it was Jefferson who was the primary author of the document that would become the Declaration of Independence. Written in poetical prose and drenched in the ideals of the Enlightenment, the Declaration would become one of the most famous documents in American history:

We hold these truths to be self-evident: that all men are created equal; that they are endowed by their creator with inalienable rights; that among these are life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness: that to secure these rights, governments are instituted among men, deriving their just powers from the consent of the governed; that whenever any form of government becomes destructive of these ends, it is the right of the people to alter or to abolish it, and to institute new government, laying its foundation on such principles, and organizing its powers in such form, as to them shall seem most likely to effect their safety and happiness.

(Meacham, 104)

The Declaration was submitted to Congress on 28 June, where it was subjected to a series of discussions and edits that made the sensitive Jefferson squirm. Eventually, a full one-fifth of the text was removed or revised to make it less radical; a section in which Jefferson blamed the king for the evils of the slave trade was taken out entirely. Finally, the Declaration was adopted on 4 July 1776, and the United States of America was born. Jefferson remained in Congress until October, then hurried back to Virginia to be closer to his wife, whose health had become quite delicate after four years of constant pregnancies. Back in Williamsburg, Jefferson helped revise Virginia's legal code to bring it more in line with the values of the American Revolution. He worked to abolish the antiquated laws enforcing primogeniture inheritance and sought to undercut the Anglican Church's monopoly on Virginians' spiritual lives by encouraging freedom of religion; in these efforts, he was aided by his protégé, James Madison, who would become his most important lifelong ally.

From 1779 to 1781, Jefferson served two single-year terms as Governor of Virginia. He worked tirelessly to keep General George Washington and the Continental Army supplied, but was taken by surprise when the British invaded Virginia in early 1781. He was too slow to call out the state militia, and he and the General Assembly were forced to flee when British troops under the turncoat Benedict Arnold converged on the new state capital of Richmond. For the rest of his career, he would be haunted by his flight, which his opponents presented as cowardice. Yet the state, and indeed the country, were saved when Washington won the Siege of Yorktown that October, effectively ending the American Revolutionary War. Whatever joy Jefferson must have felt quickly soured, however; on 6 September 1782, Martha Wayles Jefferson died after a difficult childbirth. Jefferson went mad with grief. As his daughter Patsy would later recall, for three weeks he did little but pace restlessly back and forth in Monticello, leaving only to ride "incessantly on horseback, rambling about the mountain" (quoted in Boles, 108).

Paris & Sally Hemings

Jefferson briefly returned to Congress for the 1783-84 session, his primary contribution being the Land Ordinance of 1784, which laid the groundwork for the settlement of western lands and the admittance of new states into the Union. He was then appointed US minister to France and arrived in Paris on 6 August 1784 with his eldest daughter Patsy and two slaves. The refined Jefferson delighted in the elegance of Paris, where he mingled with influential figures, frequented the opera, and spent extravagantly on books and paintings. He even fell in love with Maria Cosway, a beautiful – albeit married – Anglo-Italian musician, although their romantic strolls through the Parisian gardens abruptly ended when her husband brought her back to London. Jefferson was still in the city during the Storming of the Bastille and witnessed the start of the French Revolution. He advised his friend, Gilbert du Motier, marquis de Lafayette, in the drafting of the Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen, a landmark human rights document.

After having spent several years in Paris, Jefferson sent for his younger daughter Polly, who arrived in July 1787. She was accompanied by Sally Hemings, an enslaved 14-year-old girl. Hemings was the daughter of John Wayles (Jefferson's father-in-law) and an enslaved woman and was, therefore, a half-sister of the late Mrs. Jefferson. Sometime before leaving France in late 1789, Jefferson struck up a sexual relationship with the girl. While Jefferson's sympathizers like to believe their relationship was one of genuine affection, the power imbalance between master and slave – and indeed a 44-year-old man and a teenage girl – strongly suggests a coercive relationship if not outright rape. Sally Hemings' own thoughts on her situation have sadly been lost to history. She did, however, have at least one moment of control, when she refused to leave France with Jefferson unless he granted her concessions, and he ultimately agreed to free all her children when they reached the age of 21. Hemings would have six children, all believed to have been fathered by Jefferson.

Opposition Leader

He returned to Virginia in November 1789, by which time the United States Constitution had been ratified, with Washington inaugurated as the first president. Jefferson had his doubts about the Constitution, which still lacked a Bill of Rights, but nevertheless accepted an offer to join the president's cabinet as secretary of state. In this role, Jefferson often butted heads with Alexander Hamilton, secretary of the treasury. Hamilton sought to create a strong national government and turn the US into a modernized nation on par with the empires of Europe; his plans, however, would concentrate money and influence in the North at the expense of the agrarian South. Jefferson also believed that Hamilton's attempts to create a strong federal government undercut the sovereignty of the states, and thereby went against the principles of the American Revolution. This was the basis for their rivalry, which would have a large impact on the political development of the US.

In 1790, Jefferson opposed Hamilton's financial program, which included the national government's assumption of state debts. The two men reached a compromise when Hamilton agreed to support a permanent national capital in the South along the Potomac River in return for Jefferson's compliance, but tensions flared up again when Hamilton proposed the establishment of a national bank. In foreign policy, Jefferson remained an admirer of the French Revolution and urged Washington to support the budding French Republic in its struggles against tyranny. Hamilton, on the other hand, believed the French revolutionaries to be anarchic and violent, and favored policies that would strengthen ties with Britain. Jefferson chafed at Hamilton's intrusions into the realm of foreign policy, and, after President Washington proclaimed a policy of neutrality in the French Revolutionary Wars, Jefferson resigned. He returned to Monticello, where he continued to be the leading voice for the opposition, condemning the controversial Jay Treaty in 1795. Around this time, Jefferson became recognized as a leader of the Democratic-Republican Party, which supported republicanism, agrarianism and pro-French policies and opposed Hamilton's Federalist Party, which favored centralization, industry, and pro-British policies.

In September 1796, Washington announced he would not seek a third term in office, leading to the first contested presidential election in US history. Upon losing the election to the Federalist candidate, John Adams, Jefferson became vice president, a platform he used to continue rallying opposition to Federalist policies. He opposed the rising tensions with France, which ultimately boiled over into a brief, undeclared naval conflict called the Quasi-War. The Adams administration used the war as an excuse to implement the controversial Alien and Sedition Acts (1798), which Jefferson condemned as unconstitutional. He was aided in his opposition by his ally Madison, with their partnership later referred to as 'the great collaboration'. Accusing the Federalists of monarchism, Jefferson ran for president again in 1800. This time, he defeated Adams but tied with Aaron Burr; the House of Representatives broke the tie and handed the presidency to Jefferson. After a decade of opposition, the Jeffersonian party was finally in control.

Presidency

On 4 March 1801, Jefferson was inaugurated in the unfinished Capitol Building in Washington, D.C. In his speech, he urged conciliation, famously stating, "we are all Republicans – we are all Federalists." He viewed his election, sometimes referred to as the Revolution of 1800, as a reset, moving away from the aristocratic agenda of the Federalists and back toward a purer form of republicanism in the spirit of the Revolution. He appointed prominent Democratic-Republicans to his cabinet – James Madison as secretary of state, for instance, and Albert Gallatin as secretary of the treasury. Yet he resisted calls from within his own party to purge Federalists from their appointed offices. Jefferson did, however, attempt to block the appointment of the so-called 'midnight judges' that Adams had made during the lame-duck months of his presidency. This resulted in the landmark Supreme Court case Marbury v. Madison, which established the principle of judicial review.

The policies of the new administration would follow a political philosophy later referred to as 'Jeffersonian Democracy'. In a reversal of the Hamiltonian steps toward modernization, the Jeffersonian period saw a rise in agrarianism, and a reduced societal hierarchy; the practice of indentured servitude, for instance, declined during this period. Jefferson's administration also worked to dismantle Hamilton's financial system, by eliminating the despised excise tax on whiskey and getting rid of useless federal offices. Jefferson reduced the national debt from $83 million to $57 million by the end of his two terms. He also sought to reduce the 'majesty' of the presidential office. Rather than give long, grandiose speeches, most of his addresses were typically written and delivered. He received visitors regardless of their social status, and famously held weekly dinners in the White House attended by both Federalists and Democratic-Republican guests. Dolley Madison, James' wife, would often play the hostess at these functions and indeed carried out the functions of First Lady for the widower Jefferson.

Early in his presidency, Jefferson decided to stop paying tribute to the Barbary pirates of North Africa. He sent ships to the Mediterranean as a show of force in the First Barbary War, the first conflict fought by the US outside the western hemisphere. But the most impactful moment of his presidency came in 1803 when his administration finalized the Louisiana Purchase. The US bought the entire Louisiana Territory from Napoleon Bonaparte, who needed the funds for his military campaigns. Jefferson had long been obsessed with the West, which he had romanticized as an untamed bastion of liberty. He commissioned his private secretary, Meriwether Lewis, to organize an expedition to explore these new lands. The resultant Lewis and Clark Expedition (1804-1806) reached the Pacific Ocean – with Native American aid – and sent back descriptions of rivers, plants, and animals hitherto unknown to Europeans. Jefferson sent additional expeditions west as well. But the president was not the only one interested in the West – his former vice president, Aaron Burr, went to Louisiana with suspicious intentions, prompting Jefferson to issue a warrant for his arrest. Burr was tried for treason in 1807, with Jefferson pressing hard for a conviction, but he was ultimately acquitted due to lack of evidence. Jefferson, who had disliked and mistrusted Burr, had dropped him as vice president in the 1804 election, replacing him with former New York governor George Clinton.

Jefferson's second term was plagued by the shadow of the Napoleonic Wars raging in Europe. Although the US attempted to maintain its neutrality, its shipping came under attack by both Britain and France. In one notable incident, the Chesapeake-Leopard Affair, a naval scuffle between a British and an American ship resulted in the deaths and capture of American sailors in June 1807. Many Americans clamored for war, but Jefferson preferred a diplomatic solution. In December 1807, Congress asserted American neutrality by passing the Embargo Act, which put a trade embargo on all foreign nations. The act was controversial and did not stymy Anglo-American tensions, which would finally erupt into the War of 1812 a few years after Jefferson left office. One of President Jefferson's final significant actions was in 1808 when his administration abolished the slave trade (slavery itself would persist in the US for another half century).

Retirement & Death

Jefferson left office at the end of his second term in March 1809. He was succeeded by Madison, who continued many of his former mentor's policies. Jefferson returned to Monticello, where he spent his last 17 years in retirement. He sold his extensive book collection to the Library of Congress and helped found the University of Virginia in Charlottesville. He kept up with his correspondence and even mended broken friendships – in 1812, he famously began exchanging letters with his old friends John and Abigail Adams after over a decade of bitter estrangement. Most of his time, however, was spent designing Monticello's renovations, tending to his garden, or spending time with his daughter Patsy and her twelve children (Polly had died after childbirth in 1804). Jefferson died at age 83, on 4 July 1826, the 50th anniversary of independence. He was buried at Monticello. Today, Jefferson is remembered both as one of the most revered and most controversial Founding Fathers, making him as contradictory in death as he was in life.