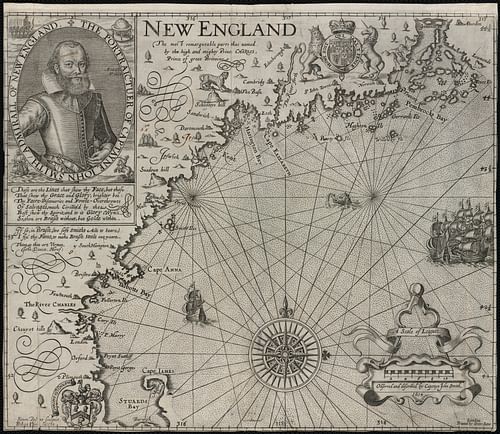

Thomas Morton (l. c. 1579-1647 CE) was an English lawyer, poet, writer, and an early colonist of North America who established the utopian community of Merrymount, sparking conflict with his separatist neighbors at Plymouth Colony and the Puritans of Massachusetts Bay Colony between c. 1626-1645 CE. He is best known for his three-volume work New English Canaan, published in 1637 CE, which criticized Puritan colonization of North America, praised Native American culture, and satirized some of the best-known figures of Plymouth Colony, notably Captain Myles Standish (l. c. 1584-1656 CE) whom he refers to as “Captain Shrimp” throughout. Morton's work, controversial in its time, is considered the first book banned in what would become the United States of America.

His colony at Merrymount was founded on a liberal interpretation of Anglican Christianity, equality of natives and colonists, and profit-sharing. Native Americans and English colonists seem to have lived and worked together under Morton's blend of English paganism, Anglicanism, and Native American spiritualism. By c. 1627 CE, Merrymount was a financial success and threatened Plymouth Colony's hold on the fur trade established in 1621 CE through their treaty with the Wampanoag Confederacy.

Morton was accused of selling guns and ammunition to the Native Americans (which he was doing) and was arrested by Myles Standish in 1628 CE who imprisoned him on an island off the coast. He was helped by Native Americans, made his way back to England, and successfully sued to have the charter for Massachusetts Bay Colony revoked (though nothing came of the suit). He returned to North America where he was caught and jailed by the Puritans and was only released due to declining health. He died in the region of present-day York, Maine. Although initially villainized by later writers, he is regarded today as a visionary and brilliant satirist, and New English Canaan is now considered one of the most important works of the Colonial Period in America.

Early Life & Background

Thomas Morton was born in Devon, England c. 1579 CE to an upper-class family, but almost nothing is known of them other than that they were Anglicans, his father had been a soldier, and Thomas was the younger of two sons. After their father died, the older brother inherited the estate, and Thomas continued his education, studying law, at the Inns of Court between the ages of 14-20. During this time, he became friends with the poets, writers, and playwrights who frequented the various taverns such as Thomas Lodge, John Donne, Ben Jonson, and William Shakespeare. It is unclear whether he ever passed the bar, but he did represent a number of low-income clients from Devonshire in court and seems to have regularly favored the cause of the poor and less privileged from the start of his career.

His defense of the poor and disenfranchised seems to have been successful and caught the attention of a wealthy widow, Alice Miller, who hired him to help manage the estate of her late husband. By 1617 CE, Miller and Morton were engaged and then married, but the relationship was challenged by her son (or stepson) George Miller, Jr. who claimed Morton was only after the family's money. George Jr. sued Morton and his mother for the estate, which was substantial, as well as for all money paid in rents from tenants. Morton represented himself and Alice in the years-long legal battle that ensued in different courts, and this seems to have brought him to the notice of Sir Ferdinando Gorges (l. c. 1565-1647 CE), later known as the “Father of English Colonization in North America”, who hired him as his lawyer.

The Miller case was still ongoing in 1622 CE and had moved up through the courts to the crown, with the recommendation that Morton should prevail, when, suddenly, he disappeared. There are no records of divorce proceedings but, in Gorges' and Morton's later works, it seems clear that Gorges needed him to go to North America on a kind of reconnaissance mission and Morton had simply abandoned his life completely and gone. The lawsuit was finally settled in favor of George jr. and no more is heard of Alice or her marriage to Morton. What the purpose of the trip was is unknown, but Morton was back in England by 1623 CE, reported to Gorges, and then left again for New England on an expedition financed by Gorges and led by Captain Richard Wollaston (d. 1626 CE) with 30 indentured servants in 1624 CE.

Mount Wollaston & Merrymount

The purpose of this expedition was the establishment of a permanent settlement in Massachusetts. Gorges had been one of the investors in an earlier attempt to settle the region in 1607 CE with the founding of the Popham Colony, but that had failed after only 18 months. The survivors who returned told of terrible weather conditions and attacks by the natives and so further colonization efforts of the region were stalled while the English focused attention on their colony at Jamestown in Virginia. Gorges applied for and received a patent to colonize present-day Maine after news of the success of Plymouth Colony reached England in 1622 CE through the work Mourt's Relation, an account of the first year of the settlement by two of its leading colonists William Bradford (l. 1590-1657 CE) and Edward Winslow (l. 1595-1655 CE). Wollaston was to establish a similar colony, and Morton would handle the legal affairs for Gorges.

The survivors of the Popham Colony had complained of the weather and the natives but, when Morton had reported to Gorges in 1623 CE, his chief concern was the intolerant religious separatists of the Plymouth Colony and their arrogance. The Plymouth Colony had a strong working relationship with the Wampanoag Confederacy in trade and, especially, the fur trade which was precisely what Wollaston and Morton were supposed to launch from their colony which their leader named after himself, Mount Wollaston.

According to William Bradford, in his Of Plymouth Plantation, “Captain Wollaston took the majority of the servants to Virginia, where he hired out their service profitably to other employers” and, in his absence, Morton orchestrated a coup and took control of the colony (Book II. ch. 9). Morton, again according to Bradford, offered the remaining servants a deal by which he would share all profits with them if they rid themselves of Wollaston's man left in charge and they agreed. Wollaston seems to have died at Jamestown or en route and Morton claimed the settlement for himself.

Morton transformed the colony from a struggling fur-trading settlement to a kind of utopian community where all shared the profits equally and there was no leader nor any kind of hierarchy. He renamed the settlement Mount Ma-re (from the French mer for “sea” but a play on the word “merry”) which came to be known as Merrymount and referred to himself as “Mine Host”, welcoming anyone who wanted to join his party. According to scholar Jack Dempsey, he modeled his community on the values of his native Devon, a region long associated with free-thinking, care for all regardless of class, and rebellion:

[Morton as] "Mine Host"…loved good hospitality [which] came of deep-rooted traditions of Devon's "outdoor people" including the belief that food-sharing (like a hunter's food-providing) was eucharistic, and not to be a weapon of social ideology: he repeatedly notes whether everybody around him is well-fed and wittily takes apart people who prevent it, especially those both inept and righteous. (xxiv)

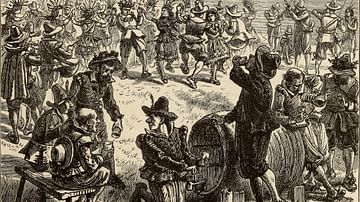

He made a concerted effort at welcoming the Native Americans to his commune and treating them as equals. In time, he blended their beliefs and practices with his own Anglicanism and ancient pagan traditions from Devon. He erected a Maypole in the town square in 1627 CE adorned with antlers at the top and encouraged drinking, poetry reading, dancing, and general revelry as often as it could be managed.

The Native Americans gladly showed the Merrymount colonists how to plant crops, fish, hunt, and provided them with the best furs while Morton gave, traded, or sold them guns, and ammunition to hunt with and for personal defense. Within two years, Merrymount was a productive and lucrative settlement. This development pleased Gorges, who received a handsome return on his investment, and was equally pleasing to Morton; but others in the area were far from happy about it.

Conflict with the Neighbors

By this time (c. 1628 CE), the nearby Plymouth Colony had firmly established itself as trade partner with the natives and, as Bradford points out, had broken the ground and paved the way for those who followed, none of whom, in his opinion, had proven themselves as worthy as the passengers who had arrived on the Mayflower. The colony established at Wessagussett had provoked the first conflict between colonists and Native Americans, and now there was Merrymount which, according to Bradford, was a hotbed of atheism and satanic rites:

Morton became lord of misrule and maintained, as it were, a school of Atheism. As soon as they acquired some means by trading with the Indians, they spent it in drinking wine and strong drinks to great excess – as some reported, 10 pounds worth in a morning! They set up a Maypole, drinking and dancing about it for several days at a time, inviting the Indian women for their consorts, dancing and frisking together like so many fairies – or furies, rather – to say nothing of worse practices. It was as if they had revived the celebrated feasts of the Roman goddess Flora, or the beastly practices of the mad Bacchanalians. Morton, to show his poetry, composed sundry verses and rhymes, some tending to lasciviousness and others to the detraction and scandal of some persons, affixing them to his idle, or idol, Maypole. (Book II.ch.9)

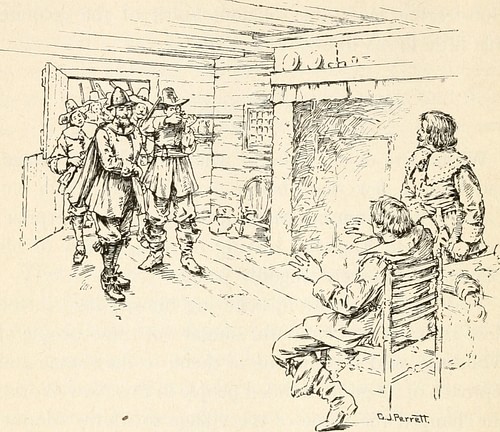

Bradford sent Morton at least two letters telling him to stop trading with the natives, especially to stop the sale or trade of arms, which Morton laughed off. Finally, he sent a party led by Myles Standish (one of the principal people mocked by Morton in his works as “Captain Shrimp” owing to Standish's small stature) to arrest him. Bradford reports that Morton and his company were all too drunk to resist Standish who arrested him easily while Morton gives another version of the event:

The Separatists, envying the prosperity and hope of the plantation at Ma-re Mount (which they perceived began to come forward and to be in a good way for gain in the Beaver trade) conspired against Mine Host especially…and made up a party against him and mustered up what aid they could, accounting of him as of a great Monster…and set upon My honest Host at a place called Wessaguscus where (by accident) they found him…The Conspirators sported themselves at My honest Host, that meant them no hurt; and were so jocund that they feasted their bodies and fell to tippling as if they had obtained a great prize. [Later, after they were drunk and had fallen asleep, Mine Host escaped back to Ma-re Mount]. Their grand leader, Captain Shrimp took on most furiously and tore his clothes for anger to see the empty nest, and their bird gone. (141-143)

Standish and his men tracked Morton to Merrymount where he agreed to surrender on the condition that he not be injured nor anyone in the settlement harmed. After he lay down his arms, however, he was attacked and bound by Standish and his men who then marooned him on the Isle of Shoals off the coast without provisions in the hope that he would starve to death. Morton was assisted by Native Americans, however, who fed and provided for him on the island until he could take ship and return to England.

New English Canaan

Morton came back in 1629 CE, ironically, at the invitation of one of the leading citizens of Plymouth Colony, Isaac Allerton, Sr. (l. c. 1586-1659 CE), who had hired him as his clerk. After no doubt clashing with Bradford and Standish, Morton returned to Merrymount shortly before the Puritan John Endicott (l. c. 1600-1665 CE), future governor of the Massachusetts Bay Colony, arrived. Endicott had the Maypole at Merrymount cut down and burned the settlement in Morton's sight after arresting him for alleged abuses concerning the natives. Morton was sent back to England where, with the support of Gorges, he sued the Massachusetts Bay Company and its colony to have their charter revoked. The legal briefs he prepared as part of these lawsuits became the rough draft of his three-volume work New English Canaan.

The title refers to the biblical account of the Hebrews under their general Joshua taking the land of Canaan from the indigenous people. In Morton's view, the Puritans and separatists were doing the same thing in North America, displacing the natives and destroying their culture in the interests of profit while justifying their actions in the name of their god. In the first volume he gives a detailed account of Native American beliefs, practices, and values; in the second, an in-depth discussion of the wildlife, landscape, and fauna; in the third, the behavior of the separatists and Puritans in the land, their poor treatment of the natives, and their improper use of resources.

To Morton, the whole paradigm of colonization was wrong and needed to be stopped. As he had demonstrated at Merrymount, colonization of North America could be accomplished peacefully with both colonists and natives profiting equally, sharing all things in common, while, according to the present model as established by the Plymouth Colony, English were arriving in the New World, taking land that did not belong to them, and fencing it off from its rightful owners whom they then expected to help them exploit the land's resources.

The book was confiscated by the English government upon publication, not because of its content, but because it was thought to be a seditious tract – such as those published by the separatists – coming from a printing house in Holland. Morton would later sue for the return of 400 editions of the work but received no response. A number of the books made it into public circulation, however, as it was known – and banned – by the colonies of New England shortly after its publication in 1637 CE.

Conclusion

Morton's lawsuit against the Massachusetts Bay Company and its colony was successful, and he planned to return to the colonies with Gorges and install him as the new governor. Gorges had already established colonies in Maine, however, had been given the title "Governor of New England" (though he had never and would never set foot there) and had no interest in pursuing the matter. The English Civil War (1642-1651 CE) then rendered the lawsuit meaningless since royal resources were directed to the conflict and no one could enforce the decision.

Morton returned to Massachusetts alone in 1642 CE and was jailed in Boston by 1644 CE on trumped-up charges as a "Royalist Agitator" for which there was no evidence; he was actually imprisoned because of his book (which may or may not have actually been read in New England) which Bradford characterizes as "full of lies and slanders against many godly men of the country in high position and of profane calumnies against their names and persons and the ways of God" (Book II. ch. 10). He remained in prison for at least a year while the prosecution was allegedly "gathering evidence" against him.

He petitioned for release in 1645 CE on the grounds of failing health and was exiled from the jurisdiction of the Massachusetts Bay Colony. He made his way to Maine and found friends among Gorges' colonists with whom he lived until his death in 1647 CE. He was buried in present-day York, Maine in Clark's Lane Burial Ground (no longer extant) and was long remembered by the Puritans and separatists for the “wickedness” of his life and his scandalous book.

Morton was still regarded in this same way in the 19th century CE as referenced in correspondence between John Adams (l. 1735-1826 CE) and Thomas Jefferson (l. 1743-1826 CE) between 1812-1813 CE in which, among other insults, Adams refers to Morton as an "incendiary instrument of spiritual and temporal domination" (Mancall, 3). In 1832 CE, American writer Nathaniel Hawthorne (l. 1804-1864 CE) challenged this view when he published his short story The May-Pole of Merry Mount, a fictionalized telling of Endicott's destruction of the Maypole and burning of the colony, later republished in the popular Twice-Told Tales in 1837 CE. Although Morton himself does not appear by name in the story, the colony he founded is held up as a paradigm of freedom and jollity as contrasted with the Puritan legalistic restrictions and gloom. The popularity of Hawthorne's work encouraged others to reevaluate Morton and his legacy.

By the 20th century CE, Morton's reputation had significantly improved as he is cited by the writer Charles Edward Banks in 1931 CE as the one emigrant to our shores who added something to the joy of life in the drab communities that surrounded him" (Dempsey, xi), and in 1971 CE, he is featured as the freedom-loving hero, imprisoned by the intolerant Puritans in the play Thomas Morton in the Promised Land by Lance Carden (Dempsey, xiii). In the present day, Morton is generally regarded positively as a forward-thinking progressive ahead of his time, and New English Canaan is considered a classic of the Colonial Period of America.