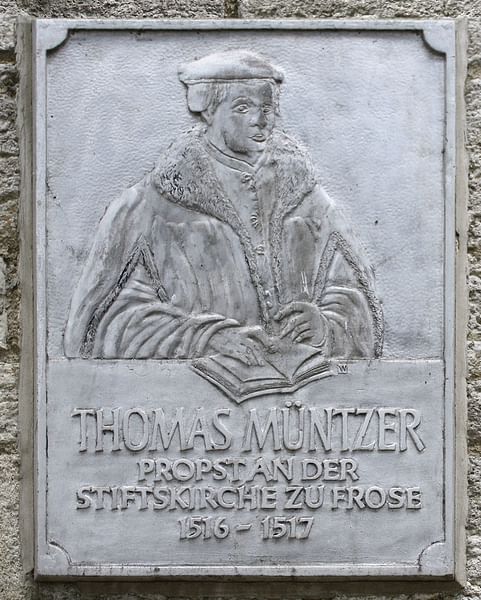

Thomas Müntzer (l. c. 1489-1525) was a German theologian and apocalyptic preacher who became one of the leaders of the German Peasants' War (1524-1525). An early follower of the reformer Martin Luther (l. 1483-1546), Müntzer established his own movement, which was condemned by Luther as too radical and contributed to the Peasants' War.

Müntzer was a Catholic priest who began questioning the practices of the Church as early as 1514 and supported Martin Luther's 95 Theses when they were published and disseminated between 1517-1519. He remained committed to Luther's vision until 1521 when, after the Diet of Worms, Luther was taken into protective custody by the noble Frederick III (the Wise, l. 1463-1525) and, afterwards, refused to support the cause of the German Peasants' War.

Müntzer harshly criticized Luther in writing for this perceived betrayal in his Vindication and Refutation of 1524 after Luther had denounced him as a rebel and troublemaker. Rejecting Luther's claim that the Bible is the sole spiritual authority, Müntzer embraced German mysticism and held that dreams – as well as signs and portents – were equally valid means by which God communicated with humanity.

He became an inspirational leader during the German Peasants' War and was arrested, tortured, and executed in May 1525 following the Battle of Frankenhausen. Although he and other leaders of the German Peasants' War were vilified afterwards, most notably by Luther, his legacy was revaluated in the 19th century by Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels in The Communist Manifesto, where he is depicted as a proto-Communist leading the working class to overthrow a corrupt capitalist system. Recent scholarship continues to debate his significance to the German Peasants' War and the Protestant Reformation overall.

Education & Luther

Although Marx and Engels portray Müntzer as a peasant, he was most likely a member of the emerging middle class of merchants as he was well-educated. Nothing is known of his early years except that he was born in the village of Stolberg around 1489, and the family moved to the town of Quedlinburg around 1490. He was a student at the University of Leipzig in 1506 and studied at Viadriana University in 1512. By 1514, he was a village priest in the village of Braunschweig and began questioning the teachings of the Church.

It is unclear what degrees Müntzer graduated with or even his course of study, but his later writings give evidence of a theological background and a close reading of the Bible – something not all priests at the time could claim. Müntzer objected to the Church's sale of indulgences – writs claiming to shorten one's stay, or that of a loved one, in purgatory – three years before Luther wrote and posted his 95 Theses on that same issue. At some point, Müntzer left his position and traveled to Wittenberg, but this would have been prior to Luther's posting of the 95 Theses on 31 October 1517.

It is unclear why Müntzer came to Wittenberg, but he seems to have become a member of Luther's inner circle, which also included the priest and theologian Andreas Karlstadt (l. 1486-1541) with whom he would later bond in attacks on Luther. At the time, however, both Karlstadt and Müntzer admired Luther and his vision for reform. Müntzer left Wittenberg sometime after Luther posted the 95 Theses and took a position in Jüterbog filling in for a pastor, Franz Günther, who was on leave.

Günther had already been preaching the reformed version of Christianity, which most likely prompted his leave of absence, and Müntzer continued this policy. He preached Luther's vision but departed from the insistence on the Bible as the sole spiritual authority, claiming that one could have direct communion with God through prayer and contemplation and God would meet the believer in dreams, through visions, and by signs and portents. Müntzer adopted this belief from the theologian and mystic Meister Eckhart (l. c. 1260 to c. 1328) whose views were discussed in the works of the Dominican friar Henry Suso (l. c. 1295-1366) and others.

Eckhart's vision of the living trinity, accessible to any believer who sought communion, seemed to Müntzer to sideline the scriptures as stories of how people in the past established their relationship with God, not as an authority on how one should do so in the present. Even so, and although he was already preaching a vision at odds with Luther's, he considered himself a Lutheran and attended the Leipzig Disputation in 1519, supporting Luther and Karlstadt in their debate against the Catholic delegate Johann Eck (l. 1486-1543). Luther, grateful for his support, suggested him for a position in Zwickau, which, unknown to either of them at the time, would encourage their break.

Mysticism & Break with Luther

The position in Zwickau, like the one in Jüterbog, was as interim pastor while the full-time Lutheran pastor, Johann Egranus, was on leave. Shortly after arriving, Müntzer met the radical reformer and mystic Nikolaus Storch (d. c. 1536) and his colleagues, known as the Zwickau Prophets, who advocated the same direct relationship with God that Müntzer had been exploring. Storch and the others believed the Holy Spirit communicated with those who were open to its messages, and one needed to rely on one's faith in the truth of this relationship, not on the Bible, to understand God's will.

The Zwickau Prophets claimed the Holy Spirit had revealed the Last Days had come and Jesus Christ would soon return to judge the living and the dead. People had to make ready, they preached, and set their affairs in order quickly. They rejected infant baptism as a human construct and agreed with the Anabaptists that only adult baptism confirmed one in the Christian faith, although this seems to be the only point the Prophets and Anabaptists fully agreed on.

Müntzer still considered himself a Lutheran, although his sermons no longer reflected Luther's vision, but was popular enough to be given a permanent position at another church when Egranus returned to resume his duties at St. Mary's. In April 1521, Luther appeared at the Diet of Worms to defend himself against charges of heresy and, afterwards, was taken into protective custody by the nobleman Frederick III. At this same time, the Zwickau town council dismissed Müntzer for his radical theology, and he left for Prague, hoping to find like-minded Christians in the city that had supported the proto-reformer Jan Hus (l. c. 1369-1415).

In Prague, he presented himself as a Lutheran, but in the six months he was there, from June to December 1521, he preached the same apocalyptic and mystical vision of Christianity as he had in Zwickau and was forced to leave the city. By this time, he had broken with Luther, believing the reformer had betrayed his original vision in order to appease nobles like Frederick III and other upper-class supporters such as Philip I of Hesse (l. 1504-1567). He attacked Luther in writing, referring to him as "Doctor Liar," among other epithets, and claiming he was only a pawn of the upper class. Luther responded by denouncing Müntzer as a radical, dismissed the Zwickau Prophets as the "Murder Prophets," warning them against inciting insurrection.

Allstedt & the Sermon Before the Princes

The peasants had rallied to the Reformed movement, especially after Luther's speech at the Diet of Worms, as they saw him as their champion who would overturn the social hierarchy and end their oppression. The peasant class suffered at the very bottom of the class structure and were taxed by the nobility, the lesser nobles, and the Church, which demanded 10% of their wages as tithes as well as other fees for various services. Luther's rebellion seemed the beginning of a radical change that would offer the lower class a way up from poverty.

Luther was condemned as a heretic and outlaw after the Diet of Worms and was only saved from execution by Frederick III hiding him at his stronghold of Wartburg Castle. He continued to write, however, and once they knew he was still alive, the peasants of Wittenberg revolted, encouraged by his stand at Worms and the apocalyptic message of the Zwickau Prophets. The peasants seem to have equated the Prophets' message with Luther's, but Luther emerged from Wartburg to denounce the violence and the "Murder Prophets," restoring peace.

Meanwhile, Müntzer had secured a position in the village of Allstedt, Saxony, preaching fiery sermons in German that drew large crowds. When word reached Luther of Müntzer's popularity and the content of his sermons, he summoned him to Wittenberg in 1524 to explain himself. Müntzer refused and, instead, continued to preach his vision until he was called by the local nobility to present his beliefs before them in his Sermon Before the Princes. Luther responded with his Letter to the Princes of Saxony about the Rebellious Spirit, charging Müntzer with inciting insurrection, and Müntzer then wrote his Vindication and Refutation, attacking Luther as an "arrogant fool" who refused to take the Reformation to its natural conclusion because he was a pawn of the nobility. Müntzer writes:

He is a herald, who hopes to earn gratitude by approving the spilling of people's blood for the sake of their earthly goods; something which God has never commanded or approved. Open your eyes! What is the evil brew from which all usury, theft, and robbery springs but the assumption of our lords and princes that all creatures are their property? The fish in the water, the birds in the air, the plants on the face of the earth – it all has to belong to them! To add insult to injury, they have God's commandment proclaimed to the poor: God has commanded that you should not steal. But it avails them nothing. For while they do violence to everyone, flay and fleece the poor farm worker, tradesman, and everything that breathes, yet should any of the latter commit the pettiest crime, he must hang. And Doctor Liar responds, Amen. (Janz, 165)

Müntzer maintained that a Christian must suffer for the faith in order to truly represent Christ and must fear only God, rejecting any fear of the opinions or threats of men. Luther, he claimed, had betrayed Christ by selling himself to the nobility in exchange for personal safety and support for his movement. Müntzer's vision appealed to the peasantry of Allstedt, who had also become disillusioned by Luther's support of the status quo, but the nobility of Allstedt did not share this enthusiasm. Count Ernst von Mansfeld, who governed Allstedt, tried to discourage attendance at Müntzer's services, but his efforts failed.

He delivered his famous Sermon Before the Princes on 13 July 1524, based on the biblical Book of Daniel, chapter 2, casting himself in the role of the prophet Daniel. In this work, he encouraged the princes to listen to the appeals of their people, make reforms in accordance with scripture, and govern as God intended before they brought divine wrath down upon themselves and the region.

The nobles were not impressed and did nothing to act on Müntzer's sermon, but after Luther attacked it in his Letter to the Princes of Saxony about the Rebellious Spirit, Müntzer was chastised and, afterwards, left the city in August 1524. Müntzer's response in his Vindication and Refutation was suppressed. Although the people still seem to have supported him, the nobility clearly did not, and he fled to the city of Mühlhausen.

The German Peasants' War

Müntzer had married a noble while in Prague, Felicitas von Selmenitz, 1523, who had given birth to a son by this time, but, feeling he needed to leave Allstedt quickly, he left them behind. At this time, the early insurrections that would lead to the German Peasants' War had already broken out in the south, and Müntzer encouraged the same in Mühlhausen while he waited for his wife and son to join him. Once they arrived, he traveled with them south to encourage the rebels. He seems to have felt that, if Luther had abdicated leadership of the Reformation, that responsibility now fell to him.

Still preaching the imminent apocalypse, Müntzer continued his attacks on Luther while helping to organize peasant bands into armed forces. Scholar Lyndal Roper describes the escalation of hostilities:

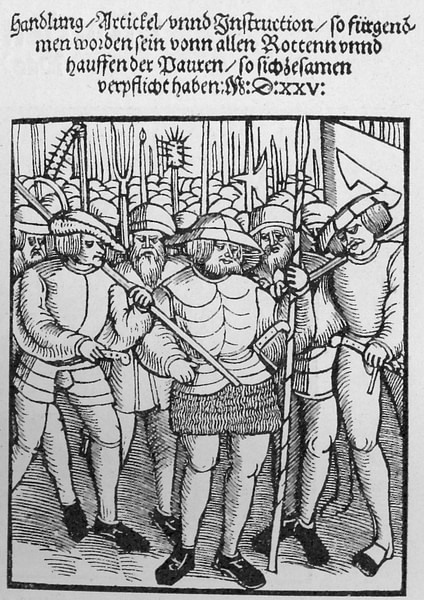

The revolts often began locally with an informal strike, as peasants simply refused to work. A meeting of the commune might be summoned by ringing the storm bell, and the heads of households would consult together…Matters might escalate as a rally was held, drawing peasants from a wider area, and eventually larger groups of armed bands formed that were bound together by oaths of brotherhood. These peasant bands, armed largely with pikes and swords, had remarkable success. By the early summer of 1525, they were in control of vast swathes of south and central Germany, largely because there was no one to stop them. The imperial armies were fighting in Italy. (251)

The early success of the revolt encouraged Müntzer and others such as the lesser noble Florian Geyer (l. c. 1490-1525) and the peasant leader Hans Müller (d. 1525) to press the nobility for the redress of wrongs and genuine change. In March 1525, the peasants submitted the Twelve Articles to the nobles of the Swabian League, demanding fair taxation, more equitable laws, and greater personal freedom. Although the Articles were rejected, the peasant leaders had an official platform to rally others to.

There was little reason for this encouragement, however, because, although many princes were engaged in foreign wars, there were still some who were quite capable of putting down any revolt. Among these was Georg III, Truchsess von Waldburg (l. 1488-1531), who defeated the peasants at the Battle of Leipheim in April 1525 and won every other engagement through May when he slaughtered approximately 3,000 peasant soldiers at the Battle of Boblingen. Müntzer, in command of his own force, supported (sometimes) by Geyer and his Black Company of knights, struck small blows against the enemy, but his primary contribution was inspiring peasants to join the cause through incendiary sermons promising the return of Christ any day and the eternal reward one could expect in fighting on Godás side for justice.

A few days after the Battle of Boblingen, on 14 May 1525, Müntzer and his troops arrived at the town of Frankenhausen where he would make a stand against the combined forces of Philip I of Hesse and George, Duke of Saxony (l. 1471-1539) the next day, 15 May. The peasant army was outnumbered, poorly armed, and lacked the kind of leadership that might have at least allowed them a fighting chance. Scholar Brad S. Gregory describes the brief Battle of Frankenhausen:

[Müntzer] assured several thousand peasants marching under his covenantal rainbow banner that God would vanquish the enemy. Yet when the slaughter of his peasants at Frankenhausen began, he seems to have fled quickly. Authorities found him hiding in a bed in the city. By the end of the month, they had executed him. (204)

When he was found in the house in Frankenhausen, Müntzer claimed he was a poor, sick man who had nothing to do with the peasants' revolt. A bag he had with him, containing documents and letters, however, identified him, and he was arrested. As with many of the rebel leaders, Müntzer was tortured before execution, and his head was placed on a pike as a warning to others. The fates of his wife and son are unknown. Although most of the people of Frankenhausen were massacred, there is evidence Felicitas Müntzer was still alive in August 1525.

Conclusion

Luther continued to denounce Müntzer throughout the German Peasants' War but especially in his Against the Robbing and Murdering Hordes of Peasants in May 1525. Karlstadt had also broken with Luther about the same time that Müntzer had and was also publicly criticized by him but never in the same way that Luther attacked Müntzer. After Müntzer was executed, Luther wrote his A Terrible History and Judgement of God on Thomas Müntzer (1525) denouncing him as a "bloodthirsty prophet" and characterizing him as "murderous." The peasants who had seen Müntzer as the more sincere reformer withdrew support from Luther – at one point a group of them even stoned him – but Protestant writers of the time, even those critical of Luther's stand against the peasants and the heavy-handed tactics of the nobility, agreed in condemning Müntzer as an unhinged radical. Catholic writers, of course, denounced him as they had (and would continue to) Luther and other reformers.

It was not until the 19th century and the work of Marx and Engels that Müntzer's reputation was revaluated, and he was cast as a hero fighting for the cause of an egalitarian society where all shared in both labor and reward. Although there is certainly evidence that Müntzer sought social reform, his primary motivation was religious, and his activities were informed by his belief that he was living in the end of days and had been chosen by the Holy Spirit to lead the peasants in what he considered a Holy War.

As there was no room in the vision of Marx and Engels for the divine, Müntzer was reimagined as a devoted advocate of the working class, imbued with proto-Communist zeal. This interpretation of Müntzer still prevails among some scholars. It has also been claimed that Müntzer only saw those he led as supporting players in his dramatic vision of himself as a prophet than as people fighting for a better life for themselves and their children.

While there may be some truth to this, it is equally possible, even probable, that he was sincere in his efforts to improve the lot of the peasantry. Today, Müntzer is more often studied as an aspect of Luther's story than his own, and his importance to the cause of the Protestant Reformation continues to be debated, but between 1521 and 1525, when the movement was establishing itself, he was regarded far more highly than Luther by the majority of the German people.