Thutmose III (also known as Tuthmosis III, r. 1458-1425 BCE) was the 6th king of Egypt's 18th Dynasty, one of the greatest military leaders in antiquity, and among the most effective and impressive monarchs in Egypt's history. His throne name, Thutmose, means 'Thoth is Born', while his birth name, Menkhperre, means 'Eternal are the Manifestations of Ra'.

Both of these throne names reference important deities of ancient Egypt Thoth, the god of writing and wisdom, and Ra, the supreme god of the sun. Thutmose III was the son of Thutmose II and a lesser wife named Iset. Thutmose II (r. 1492-1479 BCE) was married to Queen Hatshepsut (r. 1479-1458 BCE), royal daughter of Thutmose I (r. 1520-1492 BCE) and a powerful woman who held the position of God's Wife of Amun.

When Thutmose II died, Hatshepsut became regent of Egypt since Thutmose III was too young to rule. She was supposed to maintain this position but, instead, declared herself pharaoh and ruled independently. Thutmose III, when he came of age and proved himself able, was given command of the armed forces by his step-mother; a choice she would not regret as he proved himself an exceptional military strategist and charismatic leader. He is often referred to in the present day as 'the Napoleon of Egypt', but unlike Napoleon, Thutmose III never lost a single engagement, expanded and maintained his empire, and was worshiped by his people for centuries after his death.

Youth Under Hatshepsut & Rise to Power

Thutmose III was born c. 1481 BCE and was only three years old when his father died and Hatshepsut was made regent and then reigning monarch. He grew up at the royal court of Thebes, capital of Egypt throughout most of the period of the New Kingdom (c. 1570 - c. 1069 BCE). Although there is little documentation of his life during this time, a great emphasis was placed on the physical and intellectual development of princes during the New Kingdom of Egypt as they were expected to one day rule over an expanding empire.

Thutmose III, therefore, would have spent a great deal of time in school, at athletics, and learning about military tactics and strategies. He probably went along on the early campaigns Hatshepsut commissioned as this was a common practice among New Kingdom pharaohs to acquaint their successors with warfare at an early age. During this time, Thutmose III developed skills in archery, horsemanship, hand-to-hand combat, and athletic ability. There is no doubt that military training was his priority but his education went far beyond battle tactics and the use of weapons; his later reign makes clear he was a highly cultured and sophisticated man who was aware of the value of cultures beyond Egypt's borders, recognized the importance of art and music, and had a great respect for human life.

While he was growing up, his step-mother was reigning over one of the most prosperous periods in Egypt's history. After the initial campaigns to secure her position, there were no others throughout Hatshepsut's reign and the army was only deployed in small troops to protect trade expeditions and to maintain the borders. Hatshepsut did not allow her military to stand idle, however, or weaken as evidenced by how quickly Thutmose III was able to mobilize and lead the armies once he came to power.

Hatshepsut may have married her daughter Neferu-Ra to Thutmose III in order to secure succession but it does not seem, after his youth, that he spent much time at court. Orientalist James Henry Breasted has suggested he would have probably lived among the soldiers from a fairly early age in order to stay out of Hatshepsut's way and prove himself useful to her reign. It was common enough for noble princes to be removed at the discretion of a reigning monarch who perceived them as a threat and Thutmose III shows too great an ambition to have made himself so vulnerable.

That he succeeded in his plans is evidenced by the fact that, before the end of her reign, Hatshepsut had placed him in command of her armies. Her reign ended with her death in 1458 BCE, and Thutmose III came to the throne. Hatshepsut had maintained a tight control of Egypt's borders and provinces, but with her death, the kings of Egyptian-controlled states in Canaan and Syria rebelled. Thutmose III was not interested in negotiation and certainly was not going to let these provinces simply leave the empire, and so he set out on his first military campaign.

Military Campaigns

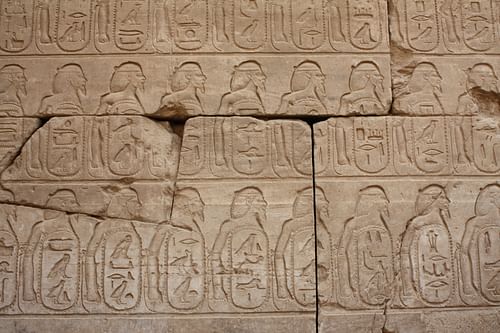

In his time as pharaoh, Thutmose III would lead 17 successful military campaigns in 20 years. He ordered the details of his victories to be inscribed at the Temple of Amun at Karnak and they are considered the most extensive records of ancient Egyptian military campaigns extant. His first is his most famous – The Battle of Megiddo – and is the one described in the most exacting narrative. His later campaigns lose this form and are given with less detail, appearing more as lists of spoils than narratives of the king's victories.

The reason for the decline in narrative form is not clear, but the claim of some scholars that it indicates a stronger cohesion of the state in which pragmatic lists of goods superseded narratives of a pharaoh's victory is untenable; there are a number of such narratives in the centuries following Thutmose III's reign, most notably that of Ramesses II (r. 1279-1213 BCE) concerning Kadesh and Ramesses III (r. 1186-1155 BCE) regarding his victory over the Sea Peoples. The most reasonable explanation for the brevity of the later inscriptions is simply that the writer of the Megiddo narrative died.

The story of the Battle of Megiddo was written by Thutmose III's private secretary, military scribe, and general Tjaneni (also given as Thanuny, c. 1455 BCE) who was with him throughout the event. Tjaneni kept a journal on a leather scroll (later deposited for posterity at the Temple of Amun in Thebes) which Thutmose III so admired he ordered the narrative inscribed on the walls of the temple as well as those of others throughout Egypt.

Tjaneni provides a detailed description of Thutmose III as a commander-in-chief fully aware of his abilities and those of his troops and completely confident of victory. In the most famous passage of the account, the pharaoh calls a conference with his senior staff to discuss marching orders to Megiddo and tells them they will be taking the narrow road from Aruna, on which the army will have to march single-file, rather than either of the wider and more easily travelled roads which were available.

The generals object to this, arguing that they have intelligence the enemy is waiting for them at the pass to the plains of Megiddo from the Aruna road and their rearguard will still be marching while the vanguard is engaged with the enemy. Thutmose III hears their counsel but disagrees, telling them that they may take whatever road they choose but he will be leading his army along the Aruna road and will be leading from the front. The generals then agree to follow wherever he chooses to take them.

His decision on the Aruna road was characteristic of Thutmose III's resolve to pursue a course he considered best regardless of the difficulties. The armies would have had an easier time on the other roads – especially considering that, on the Aruna path, they had to dismantle and carry the chariots and supply wagons – but it would have cost the army the element of surprise which Thutmose III recognized as imperative.

As it turned out, the enemy was not waiting at the end of the Aruna road but on the two easier paths which they expected Thutmose III to take at the head of so large an army. No one expected him to lead his forces along what was essentially a cattle path. After giving his army a night to rest and refresh themselves, he ordered the attack the next morning, leading from the front, and drove his opponents from the field. The report then details how his army, delighted at the victory, gathered treasures from the fallen instead of pursuing survivors and taking the city. This cost Thutmose III complete victory on the field that day because it gave the people of Megiddo time to prepare their defenses.

Even so, Thutmose III marched on the city, surrounded it with a moat and a stockade, and lay siege to it for seven or eight months until it surrendered. He offered very generous terms to the people – none of the surviving ringleaders of the revolt were executed – which essentially came down to a promise not to incite rebellion in the future. He then turned his army around and marched back home with his enormous loot from the campaign, pausing only to harvest the crops of the defeated and bring them back to Egypt.

At Megiddo, he also initiated a policy he would adhere to throughout all his campaigns of bringing the noble children of the defeated kings back to Egypt to be educated as Egyptians. These children were held as hostages to guarantee the good behavior of their parents but were treated with all the respect due to royalty, housed in the palace, and given many freedoms. When they came of age, they were allowed to return home where, since they had now spent their youth in Egypt, they supported and encouraged Egyptian culture and the state's interests when they were elevated to positions of power.

Thutmose III's victory at Megiddo gave him control of northern Canaan from which he would launch his campaign into Syria to take Kadesh. He campaigned against the Mitanni and erected a stele at the Euphrates River, commemorated in his inscription at Karnak, known as Thutmose III's Hymn of Victory. His Nubian campaigns were equally successful, and by his 50th year, he had expanded Egypt's holdings beyond any of his predecessors and made the country wealthier than it had been since the beginning of the 4th Dynasty of the Old Kingdom of Egypt (c. 2613- 2181 BCE).

Patron of the Arts

His reign was not only focused on military conquest, however, as his patronage of the arts shows. Thutmose III commissioned upwards of 50 temples, numerous tombs, monuments, and contributed more significantly to the Temple of Amun at Karnak than any other pharaoh. His renovations and additions to the Karnak temple, in fact, are among the most significant in that they preserve the names of past kings (whose monuments he would sometimes remove in his renovations) and provide narratives of his own campaigns and initiatives which have proven to be extremely important to scholars in the study of the culture.

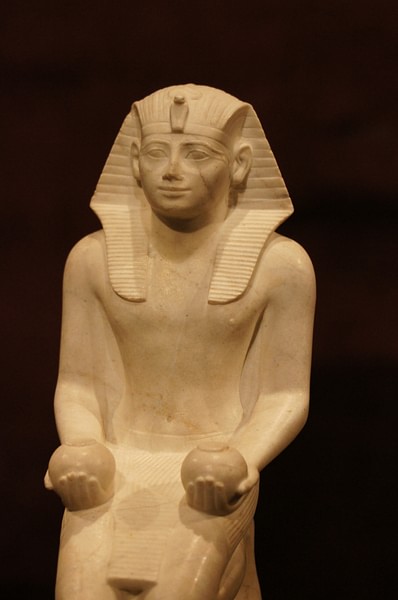

Artistic techniques and experimentation reached new heights under Thutmose III. Glass-making had been known for centuries but was now perfected to the point where drinking vessels could be made of glass. Statuary was less idealized and more realistic – a trend begun in the Middle Kingdom of Egypt (2040-1782 BCE) – but abandoned in favor of the traditional idealism in art established during the Old Kingdom. Thutmose III is depicted in his statuary as a tall, handsome man in excellent physical condition and this is considered a realistic portrayal in that, first, all depictions are uniform and, second, depictions of others – also consistent – are far from flattering.

His artisans produced some of the finest work in Egypt's history including elaborate tombs decorated with intricate paintings and freestanding columns as well as contributing enormous pylons to Karnak. In keeping with Egypt's respect for and love of nature, he encouraged public parks and gardens, created lakes and ponds for the people's recreation and enjoyment, and had a private garden cultivated both around his palace and at Karnak temple.

Defacement of Hatshepsut's Monuments

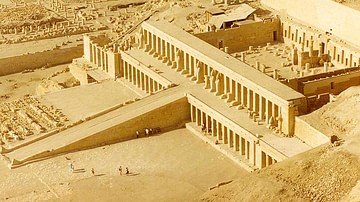

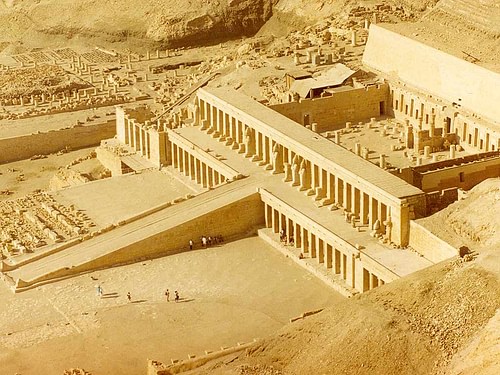

His artistic sensibilities and respect for others are at odds with a policy almost universally ascribed to him: the desecration of Hatshepsut's monuments and the attempt to erase her name from history. Scholars are divided on when this happened in his reign but it was certainly not in the early years. Whenever it transpired, the name and images of Hatshepsut were removed from all public monuments as well as the exterior and some of the interior work at her mortuary temple at Deir el-Bahri.

To remove a person's name was to condemn them to non-existence; one needed to be remembered in order to continue one's eternal journey in the afterlife. Further, it was thought that the deceased needed daily sustenance in the form of food and drink offerings delivered to their tombs, where their body was preserved through mummification and statues representing them enabled their soul to visit and partake of these offerings. The so-called Execration Texts of ancient Egypt make clear that the removal of one's name was only justified if that person had committed some serious offense, but there is no evidence of Hatshepsut being involved with any such crimes.

Most likely, Thutmose III ordered this action to prevent Hatshepsut from standing as a role model for future women who might aspire to rule. The position of the monarch of Egypt was traditionally occupied by males and, by assuming power for herself, Hatshepsut had departed from this practice. The first king of Egypt was thought to have been the god Osiris who was murdered by his brother Set and brought back to life by his sister-wife Isis. He was finally succeeded by his son Horus who defeated Set, took back the throne, and re-established order in the land. Kings associated themselves with Horus during their reign and with Osiris, who became Lord of the Dead, in the afterlife; there was no place in this narrative for a woman to hold supreme power.

The central cultural value of ancient Egypt was ma'at (harmony and balance) and this relied largely on an adherence to tradition. Ancient Egyptians are often characterized as conservative for this reason: departure from tradition could result in a loss of stability – balance – and the return of primordial chaos. It was the duty of the pharaoh to maintain ma'at and this is probably the motivation behind Thutmose III's eradication of Hatshepsut's name.

He backdated his reign to remove all evidence of her ever having ruled Egypt and replaced some of her images in her mortuary temple with his own. All of her public monuments were torn down – especially those at Karnak – and replaced by his, though, at other sites, only her name was removed. So thorough was this erasure of his predecessor that Hatshepsut's name was unknown in Egypt's history until the 19th century CE. Later kings of Egypt thought the beautiful Temple of Hatshepsut at Deir el-Bahri was built by Thutmose III, and many of them would claim her impressive monuments as their own.

It has been suggested that Thutmose III had nothing to do with these actions and that they were perpetrated by his son and successor Amenhotep II (r. 1425-1400 BCE) either in the latter part of Thutmose III's reign or the beginning of his own. Although this is possible, it does not seem probable in that, by the time of Amenhotep II, Thutmose III had already ordered Hatshepsut's works at Karnak removed and replaced by his own. Further, the image and name of Hatshepsut was left intact within the interior of her mortuary temple.

If Amenhotep II, who never knew Hatshepsut, was trying to erase her from history, it is unlikely he would have spared her memory anywhere. Leaving her name and image intact, but out of the public eye, suggests that Thutmose III was only interested in maintaining the tradition of a male pharaoh in Egypt's history but did not wish his step-mother any ill will.

When he died, of natural causes, in c. 1425 BCE, he was buried in his own mortuary temple beside that of Hatshepsut at Deir el-Bahri. Even though he had basically claimed her temple as his own, he still would not have had his eternal resting place located so close to hers if he had sincerely believed she deserved to be sentenced to non-existence.

Conclusion

The unfortunate result of this action is that, ever since the rediscovery of Hatshepsut, Thutmose III is as often referenced for her eradication as he is for his many accomplishments and magnificent reign. Thutmose III essentially created the Egyptian empire single-handedly. He elevated Egypt's status as a powerful and prosperous nation, employed the people in monumental building projects, and epitomized the ideal of the valiant Egyptian warrior-king who led his forces to successive victories.

Thutmose III's consideration for his enemies in defeat and gentle treatment of them made him respected far beyond the boundaries of his country. He established an empire stretching from the Euphrates River in Mesopotamia, through Syria and the Levant, down through Nubia to the Fifth Cataract of the Nile.

Although there is little doubt that the people of these lands would have preferred their independence, they prospered under his reign through the peace he established and maintained through his military and diplomatic skills. In every respect, Thutmose III represented the ideal pharaoh to his people and his memory has endured to the present day as one of the greatest kings of ancient Egypt.