Timbuktu (Timbuctoo) is a city in Mali, West Africa which was an important trade centre of the Mali Empire which flourished between the 13th and 15th centuries. The city, founded c. 1100, gained wealth from access to and control of the trade routes which connected the central portion of the Niger River with the Sahara and North Africa.

Timbuktu's golden period was in the 14th century when it grew rich passing along gold, slaves, and ivory from Africa's interior to the Mediterranean and sending salt and other goods southwards. The ruler Mansa Musa built mosques of pounded earth and established universities which gained the city international fame as a centre of Islamic learning. The city thrived longer than the Mali Empire, experiencing various subsequent rulers such as the Songhai Empire, the Tuaregs, and the Moroccan Pashas, but the medieval descriptions of the city's wealth lingered long in the memory. The difficulty European explorers had in finding the city and establishing the source of the Niger River resulted in Timbuktu becoming one of the most mysterious places in world geography. Timbuktu is listed by UNESCO as a World Heritage Site.

Early History & Name

Timbuktu is a city located near the Niger River in modern-day Mali in West Africa. The area around Timbuktu has been inhabited since the Neolithic period as evidenced by Iron Age tumuli, megaliths and remains of now abandoned villages. The Niger River regularly flooded the plains between Timbuktu and Segu to the southwest, which provided fertile land for agriculture, beginning at least 3,500 years ago. In particular, red-skinned African rice, along with other indigenous cereals and foodstuffs, was grown, and local deposits of copper exploited. Copper was traded via trans-Saharan routes during the first millennium while evidence of copper ingots cast for trade purposes date to the 11th century onwards. Similarly, gold was probably locally mined and then traded, but concrete evidence from this period is lacking.

It is around 1100 that Timbuktu was founded by Tuareg herdsmen, the nomads of the southern Sahara, as an advantageous spot where land and river routes coincided. According to one legend, the herdsmen dug a well at the site and asked an old woman called Buktu to look after it whenever they were away. In the Tuareg language, Tamashek, the word for 'place' is Tin and so Timbuktu derives from the name the Tuareg's gave the place, Tin'Buktu, meaning 'place of Buktu'. A more modern but less romantic interpretation of the origin of the city's name is that it merely means 'the place between dunes'. From these humble Tuareg beginnings Timbuktu would develop into an important autonomous desert port.

The Mali Empire

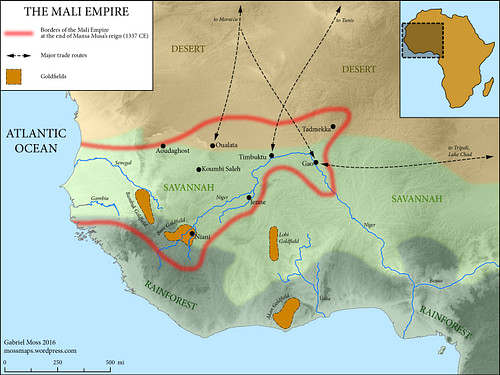

From the mid-13th century Timbuktu, then under the control of the Mali Empire (1240-1645), would reach new heights of wealth and fame, becoming the most important trading city in the Sudan region (the area from the west coast to central Africa, stretching along the southern border of the Sahara desert). The Mali Empire, with its capital at Niani, established its independence from the Ghana Empire (6th-13th century) in the 1230s thanks to its founder Sundiata Keita (aka Sunjaata, r. 1230-1255), a prince of the indigenous Malinke (Mandingo) ethnic group. Sundiata would eventually carve out an empire that controlled not only Timbuktu but also Ghana, Walata, Tadmekka, and the kingdom of Songhai, with the borders of the empire reaching the Atlantic coast. Thus, Mali became the largest and richest empire yet seen in West Africa. Indigenous rulers adopted Islam from their contact with Arab merchants, and the Mali Empire would thus play a significant part in the spread of Islam across West Africa. Locals, or at least urban ones, were converted, which created communities that then attracted Muslim clerics from the north, strengthening the religion's grip on the region. Local leaders would even perform pilgrimages to the Islamic holy sites like Mecca.

The Mali Empire flourished thanks to its control of the trade routes which connected western and central Africa to North Africa. Gold was a particularly important commodity that Mali controlled the trade of in the region, especially following the discovery of the Black Volta (in modern-day Burkina Faso) and Akan Forest (in modern-day Ghana) goldfields to the south. Rock salt from the Sahara was another highly valued commodity and was exchanged for gold dust. Timbuktu operated as the middle-trader in this exchange of northern and West African resources. A 90-kilo block of salt, transported by river from Timbuktu to Djenne (aka Jenne) in the south could double its value and be worth around 450 grams of gold. Other goods traded included ivory, textiles, horses, glassware, weapons, sugar, kola nuts (a mild stimulant), cereals (e.g. sorghum and millet), spices, stone beads, craft products, and slaves. Goods were bartered for or paid using an agreed upon commodity such as copper or gold ingots, set quantities of salt or ivory, or even cowry shells (which came from Persia).

Timbuktu was one of the most important cities in the Mali Empire because of its location near the Niger River bend and so it was fed by the trade along both the east and west branches of this great water highway. In addition, Timbuktu was the starting point for trans-Saharan camel caravans which transported goods northwards. Controlled by the Berber Arabs, the established routes went from Timbuktu to Tlemcen (Algeria) and to Fez (Morocco) stopping at known oases along the way. Such caravans typically had around 1,000 camels, but the larger ones could have up to 12,000 'ships of the desert'. Besides trade links, there were also diplomatic relations between Mali and Egypt and also Morocco. Timbuktu itself became a cosmopolitan city of Berbers and Sudanese Africans of many ethnic groups packed with craft workers and both temporary and permanently placed merchants.

Mansa Musa

From the reign of Mansa Musa I (1312-1337), mosques began to be built across the Mali Empire. A large mosque was built at Timbuktu, the 'great mosque', also known as Djinguereber or Jingereber, designed by the famous architect Ishak al-Tuedjin, who had been enticed from Cairo following Mansa Musa's visit there. The mosque was completed by 1330. A royal palace or madugu was also built in the city (but has since vanished), even if Timbuktu was not the capital. The city was overseen by a regional governor appointed by Musa who was responsible for dispensing justice amongst the population of around 15,000, collecting taxes on trade, and settling any tribal disputes. Subsequently, a third mosque was built, the Sidi Yahya, to add to the already existing Sankore (of the late 12th century). Mansa Musa also had fortification walls built to protect the city against Tuareg raids. Due to the lack of stone in the region, buildings were typically constructed using beaten earth (banco) reinforced with wood which often sticks out in beams from the exterior surfaces. Despite the limited materials, the mosques, in particular, are imposing structures with huge wooden doors and tiered minarets. Other buildings included large warehouses (fondacs) which were used to store goods before they were transported elsewhere and which had up to 40 apartments for merchants to live in.

A Centre of Learning

Islamic learning was also encouraged, with Timbuktu possessing several universities where books were accumulated in large libraries and students were trained first to memorise texts and, for higher level students, to produce commentaries and creative works based on Islamic religious texts. One noted scholar was the saint Sharif Sidi Yahya al-Tadilsi (d. c. 1464) who became the patron saint of the city. It is perhaps important to note that the religious studies were wider than we might today imagine, with traditional Islamic 'humanities' subjects including not only theology but also traditions, law, grammar, rhetoric, logic, history, geography, astronomy, and astrology. Medicine was another subject given great attention, making the city famous far and wide for its doctors.

Despite the focus on Islamic studies and the construction of mosques, ancient indigenous animist beliefs continued to be practised independent of Islam, and even the form of Islam that took hold in Mali was a local variation of that practised elsewhere. At Timbuktu, in particular, a clerical class developed, many of whose members were of Sudanese origin. These clerics and local converts and scholars frequently acted as missionaries, spreading Islam into other parts of West Africa so that it was now no longer seen as a religion of white foreigners but very much as a religion belonging to black Africans themselves.

The combination of Timbuktu's three mosques, clerical class, and universities meant that it became the holiest city in the Sudan region. It is also true, however, that because religious and other studies were not made in native languages and were restricted to a small urban elite, the impact on the education of the wider Mali population was limited. Still, the city's lasting reputation as a place of learning is encapsulated in the following West African proverb:

Salt comes from the north, gold from the south, and silver from the country of the white men, but the word of God and the treasures of wisdom are only to be found in Timbuktu.

(quoted in De Villiers, Preface)

Decline

The Mali Empire was in decline by the 15th century as trade routes opened up elsewhere and several rival kingdoms developed to the west, notably the Songhai. European ships, especially those belonging to the Portuguese, were now regularly sailing down the west coast of Africa and so the Saharan caravans faced stiff competition as the most efficient means to transport goods from West Africa to the Mediterranean and the Middle East. In addition, by the mid-15th century, the Portuguese had direct access to the Akan Forest goldfield, reducing the trade possibilities for Timbuktu. The Tuareg, led by their chief Akillu, attacked and took over the city from 1433. There were also sporadic attacks by the Mossi people, who then controlled the lands south of the Niger River. C. 1468, King Sunni Ali of the Songhai Empire (r. 1460-1591), who was vehemently anti-Muslim, conquered Timbuktu.

The Mali Empire was now reduced to controlling a small western pocket of its once great territory, and even that small area would eventually be absorbed into the Moroccan Empire in the mid-17th century. Timbuktu meanwhile, with a population of around 100,000 in the mid-15th century, fared better than the old Mali Empire and continued to thrive as a centre of learning into the 16th and 17th centuries when the city boasted 150-180 Koranic schools. Many important chronicles were produced which covered the history of the region (e,g. the Tarikh al-Sudan c. 1656 and Tarikh al-Fattash c. 1650). Timbuktu was used as a capital by the Pashas who became princes virtually independent of Morocco in the second half of the 17th century. The Pashalik of Timbuktu would end in the final quarter of the 18th century when, not for the first time, the local Tuaregs seized the advantage of a political vacuum and took over the city in 1787.

As Far as Timbuktu

Timbuktu and the Mali Empire in general received international attention in the Middle Ages thanks to descriptions in the works of Muslim travellers. The region was visited and described by the famed explorer from Tangiers Ibn Battuta (1304 - c. 1369), who travelled throughout West Africa amongst many other places in the world. Battuta, visiting Timbuktu in c. 1352, described the city in some detail, noting the mix of Islamic and animist beliefs, the efficient justice system, the slave trade, and the lack of clothing worn by Mali women. Another celebrated Muslim traveller, Leo Africanus (c. 1494 - c. 1554), also famously described Timbuktu, including the city's great wealth. Such stories as these would titillate European explorers from the 18th century, and the difficulties in finding the city along with the lengthy search for the source of the Niger River only strengthened Timbuktu's position as one of the world's most mysterious places. Not for nothing did the expression arise 'as far away as Timbuktu' or 'from here to Timbuktu', meaning as far-away a place as one could possibly imagine. Indeed, a symptom of the city's remoteness and mystique was the complete lack of agreement on even how to spell it, never mind where it actually was on the map. Even today, the fabled city remains a difficult place to reach, but if one manages it, then one can still see elements of Timbuktu's 14th-century heyday, notably the Sankore mosque with its huge library of medieval manuscripts and books which a United Nations programme is working to restore and preserve.