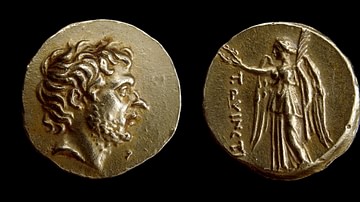

Titus Quinctius Flamininus (229-174 BCE) was a consul and military commander of the Roman Republic during the Second Macedonian War, who decisively defeated Philip V of Macedon (r. 221-179 BCE) at the Battle of Cynoscephalae in 197 BCE and negotiated the Peace of Flamininus, which established Roman control in Greece.

Early Life

Born in 229 BCE into an aristocratic family, Titus Quinctius Flamininus was fluent in Greek and a Philhellene, a lover of Greek culture. Philip Matyszak in his Greece Against Rome wrote that Flamininus was "cultured enough to reassure diplomats that they were not dealing with some western barbarian" (82). Flamininus campaigned under the Roman commander Claudius Marcellus against the Carthaginian general Hannibal (247-183 BCE) in southern Italy during the Second Punic War (218-201 BCE), was the founder of two colonies and served as a quaestor at Tarentum in 205 BCE. In his Lives, the historian Plutarch wrote (45/50 to 120/125 CE) that he had passed through the rudiments of soldiery, fought against Hannibal, served as a tribune under Marcellus, and distinguished himself as a governor, becoming "no less famous for his administration of justice than for his military skill" (415).

Consulship

In 198 BCE, Flamininus became consul alongside Sextus Aelius Catus at the tender age of 30, sidestepping the traditional rules of the cursus honorum, the ladder of Roman government offices. This quick rise to consulship earned him a number of enemies in Rome who believed themselves far more capable and qualified. Under intense pressure to succeed, he would have to bring home news of a successful campaign in Greece – a peace treaty would not do that. He understood that he had a difficult task ahead of him.

Prior to his arrival in Greece, the Roman army had done little to suppress Philip's ruthless assaults in Greece against Pergamon and Rhodes. When they asked for Rome's assistance, the city issued an ultimatum to Philip, which was ignored. According to Matyszak, Philip had few worries. Antiochus had abandoned his attention to Macedon, and by 199 BCE, Philip realized he would only have to hold off Rome to continue his assault on Greece. However, the Macedonian king would find a competent foe in Flamininus. The driving force behind the young Roman's desire to succeed was his thirst for glory. He wanted a war, and he wanted to win it. Matyszak claimed that he not only was a competent general and diplomat but he was also an excellent strategist. Plutarch wrote that "The war against Philip and the Macedonians fell to Titus by lot, and some kind of fortune." The Romans required "a general who would always be upon the point of force and mere balance, but rather were accessible to persuasion and gentle usage" (413). This was Flamininus.

Campaign of 198 BCE

However, before engaging Philip in battle, Flamininus had to consider his best strategy. Philip's strength lay in his occupation of Greece and the support he derived from its cities. To defeat the king the Romans had to simply convince the Greek cities, willingly or not, to no longer support him. However, this strategy almost proved to be unnecessary. Realizing the strength of the Roman forces with its newly arrived reinforcements, Philip was more than willing to negotiate for peace. Although Flamininus was willing to talk, peace was not his ideal option; he wanted glory in war.

At the meeting, Philip was informed of the Roman's demands to withdraw his army from his garrisons in Greece and compensate the lands he had plundered. Of course, Flamininus knew these proposals were both unreasonable and unacceptable. An angry Philip stormed out of the meeting, and Flamininus knew that he had his war. Although Philip may have been angry, he was not unrealistic or stupid and understood that he did not have the necessary manpower to engage the Romans in a prolonged war; he needed to defeat them in one swift victory.

The two armies fought outside Philip's fortifications at the Battle of the Aous. Using information gained from a local, the Romans were able to circumvent Philip's defenses at the river gorge. Flamininus sent a large enough force to attack the unexpecting Macedonian flank, and Philip was forced to make a chaotic retreat. Plutarch wrote, "The Macedonians fled with all the speed they could make; there fell, indeed, not more than two-thousands of them; for the difficulties of the place rescued them from pursuit" (415). The Romans also pillaged their camp, seizing money and slaves. With the assistance of the Aetolians, Flamininus pushed Philip into Thessaly where he declared its people free, whether they wanted it or not. The Romans' arrival split Thessaly and Epirus, forcing the latter to reluctantly surrender.

After years of oppressive Macedonian rule, many Greeks welcomed the Romans, especially the Aetolian and the Achaean League. Plutarch wrote that when the Romans "set foot in Thessaly the cities opened their gates, and the Greeks, within Thermopylae, were all eagerness and excitement to ally themselves with them" (415). Matyszak, however, claimed that this joyful reception of the Romans was not necessarily true. Many Thessalian cities, Atrax for one, did not want freedom and fought against liberation, not only due to loyalty to Philip but also because of the presence of the much-disliked Aetolians. Whatever the case, Flamininus understood that the resistance in Thessaly prevented him from entering Macedon. With winter approaching, he led his beleaguered forces to the Gulf of Corinth.

Negotiations

Over the winter, the Roman commander had a lot to consider. His consulship was about to come to an end and he wondered whether or not he would keep his command and claim the glory of completing the war. Flamininus reached out to Philip to once again negotiate peace. In the commander's mind, he would keep his command if the terms of the peace treaty were rejected by the Roman Senate. If the treaty were to be accepted and his command not renewed, he would, at least, be given credit for winning the war. If another general replaced him, honor would be lost. Whether or not his command was renewed, he was determined to obtain the glory of defeating Philip. The commander's future was in the hands of the Senate.

Philip and Flamininus met on a beach near Thermopylae (some sources say Nicaea). Not trusting either the Romans or Aetolians, the Macedonian king brought along five galleys in an attempt to intimidate. Representatives from across Greece attended, including Pergamon and Rhodes. The usual terms – withdrawal and reparations – were discussed: Pergamon, for example, wanted the Temple of Artemis and the Sanctuary of Aphrodite restored. As before, Philip objected to many of the proposals. It was finally decided that the objectionable terms would be presented to the Senate for their consideration.

Both Flamininus and Philip immediately sent envoys to Rome to present their proposals. Referencing the peace proposals, Plutarch wrote, "… if they should continue the war, to continue him in his command, or if they determined an end to that, that he might have the honor of concluding the peace" (415). Although points of contention were discussed, the Senate had already made a decision. While they listened to the envoys from the various Greek cities, Philip's representatives were not even permitted to speak. After Flamininus received word that the treaty had been rejected, the Romans marched into Thessaly. On the consular appointments, the decision had already been determined before the Macedonian envoys arrived in Rome: the newly named consuls were both sent to Gaul. Flamininus kept his command and war would resume.

Cynoscephalae

Philip was losing, abandoned by his cities one by one, and he suffered a decisive defeat at the Battle of Cynoscephalae. The armies were fairly equal: 25,000 to 30,000 men, with 2,000 Macedonian cavalry and a Roman contingency of light-armed Greeks. The night before the engagement it rained, making the ground extremely wet. To make matters worse, in the morning, the armies woke to a dense fog. Although evenly fought and balanced in the beginning, the battle ended in a disaster for Macedon when the Romans attacked their rear. To counter Roman warfare, his Macedonian phalanx required open ground. According to Plutarch, the phalanx was like a "single, powerful animal" and was successful only as long as it "embodies into one and keeps its order." (417). The phalanx formation did not allow for a rear assault, and the terrain was too rocky and uneven for Philip to maneuver.

Philip's forces fell apart, confusion followed, and the "… Macedonian battle machine had dissolved into a mass of disoriented, frightened men" (Matyszak, 88). The Macedonians dropped their pikes, a sign of surrender, but the Romans did not understand its symbolism and cut down the Macedonians where they stood. 8,000 were massacred and another 5,000 taken prisoner, while Rome only lost 700. Philip was now forced to accept the Roman peace terms.

Peace

The Treaty of Tempe, also called the Treaty of Flamininus, found Philip not only losing his fleet but also withdrawing from Greece. Besides having his army reduced to only 5,000, he was required to ask permission from Rome before any military action was taken. The treaty awarded nothing to the Aetolians who had hoped to at least receive Philip's garrisons close to their territory. They had also wanted Philip replaced, but this was impossible as Philip's absence would have created a vacuum, upsetting the balance of power in the Eastern Mediterranean. "A tamed Philip was left in the north, stripped of his external dependencies … and bound into an alliance with Rome … he accepted his new, reduced alliance with Rome." (Everitt, 318) The victorious Flamininus returned to Rome in triumph, loaded with cartloads of Greek art and treasure.

Conclusion

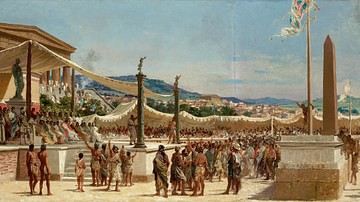

At the Isthmian Games at Corinth in 196 BCE, Flamininus declared that the people of Greece were free, although Rome's definition of freedom may have differed from that of the Greeks. The Greeks were obligated to Rome, giving their support when and where it was demanded. In return, Rome gave them protection, and Roman garrisons remained in Greece until 194 BCE. In 191 BCE, Antiochus III (r. 223-187 BCE) of the Seleucid Empire took advantage of Rome's absence and moved into Greece, accompanied by Hannibal, the old exiled Carthaginian general. Rome responded with an army under the command of Lucius Cornelius Scipio who defeated Antiochus at Thermopylae and Magnesia. In 183 BCE, Hannibal was captured by Flamininus; however, before he was sent to Rome, he committed suicide. Afterwards, history seems to have forgotten Flamininus.