Tiwanaku (or Tiahuanaco) was the capital of the Tiwanaku empire between c. 200 - 1000 CE and is situated in the Titicaca basin. At an altitude of 3,850 metres (12,600 ft) it was the highest city in the ancient world and had a peak population of between 30,000 and 70,000 residents. The Tiwanaku empire, at its largest extent, dominated the altiplano plains and stretched from the Peruvian coast to northern Bolivia and included parts of northern Chile. Tiwanaku is located near the southern (Bolivian) shores of the sacred Lake Titicaca and it would become the centre of one of the most important of all Andean cultures. The architecture, sculpture, roads, and empire management of Tiwanaku would exert a significant influence on the later Inca civilization. Tiwanaku is listed by UNESCO as a World Heritage Site.

Layout

Tiwanaku was founded some time in the Early Intermediate Period (200 BCE - 600 CE). The first examples of monumental architecture date to around 200 CE but it was from 375 CE that the city became grander in its architecture and scope. These new structures included large religious buildings, gateways, and sculptures. The layout of the city centre was constructed on an east-west axis, built in a grid design, and the whole was surrounded by a moat (perhaps only symbolic) on three sides which linked with Lake Titicaca on the fourth side of the city.

In mythology Lake Titicaca was considered the centre of the world, two islands on it were made into the sun and moon, and it was the site where the first race of stone giants was produced and subsequently, the human race. It has been suggested that many of the monuments at the site were placed in alignment with the sunrise and or the midday sun. However, the fact that many of Tiwanaku's monuments have been shifted about over the centuries makes the discovery of their original positions extremely difficult.

Outside of the moat there were residential buildings arranged in compounds and built using mud bricks. Irrigation was also provided for crops via canals, aqueducts and dikes which brought water from the lake. Such measures allowed for a successful and reliable agricultural yield (especially potatoes) and for sustained population growth so that at its peak the city covered up to 10 square kilometres.

The Sacred Centre

One of the striking features of Tiwanaku are the large open spaces for ceremonial and religious activities which employ fine monumental stonework, work which has long been admired including by the Incas. Their are two principal types of walls - those with large irregular blocks and those with fine-fitting and straight-edged blocks. Many blocks at Tiwanaku display grooves cut into them for the placing of ropes which made their transportation and positioning easier. Blocks could be held together using bronze clamps or staples, usually cast directly into T and I-shaped sockets in the stone. The precision of some of the cut blocks suggests the use of relatively sophisticated tools and instruments of measurement. An indication of these skills is that the much later Inca deliberately imported their stonemasons from the Lake Titicaca basin in direct homage to the gifted builders of Tiwanaku.

The focal point of the sacred precinct was the Akapana Temple which was an artificial hill over 15 metres high and shaped into seven tiers. Steps were cut into the east and west sides. The top of the mound was made into a flat area of 50 square metres and used to create a T-shaped sunken court. The court is paved with andesite and sandstone slabs and drainage was provided by stone channels which cascaded water down each of the terraces. The site may have been used in shamanic rituals and a High Priest was buried there with a puma effigy incense burner and puma-headed humans iconography also covers the stonework of the temple.

The Kalasasaya is another sacred structure, this time rectangular and measuring 130 by 120 metres. Its sacred sunken court provided space for public and religious ceremonies and, as a reminder of this, has severed stone heads protruding from the interior of its sandstone perimeter walls which also include regularly placed tall columns. The precinct is accessed via a single staircase which again has stone columns either side. Standing in the precinct is the Ponce Monolith, a 3.5 metre tall stone perhaps depicting a ruler, High Priest, or god of Tiwanaku. The figure holds a kero (qero) or tall beaker in one hand and a staff-like object, perhaps a sceptre or coca snuff tablet, in the other.

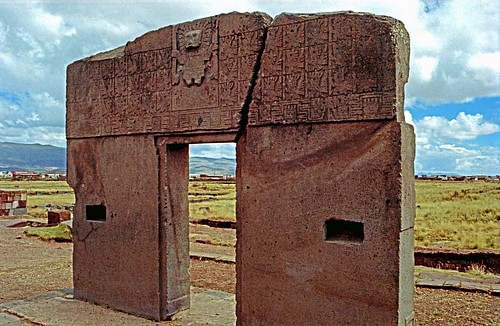

In the north-west corner (not its original position) of the Kalasasaya is perhaps the most famous structure of Tiwanaku, the monumental Gateway of the Sun. Carved from a single massive block of andesite stone, the Gateway is 2.8 metres high and 3.8 metres wide. The opening in the gate, with its distinctive double jamb, is 1.4 metre wide. The top portion has relief carvings of 48 winged demons or angels, each with either a human or bird head and wearing a feathered headress. These figures are set in three rows and in the centre is a deity who has been identified as the Staff Deity from the Chavin culture, forerunner of the Andean creator god Viracocha. The god holds a staff with condor heads in each hand (identified by some as a spear-thrower and arrows), has a mask like face, has 19 rays coming from his head which end in either a circle or puma head, and is crying, probably to signify rain. Underneath these figures is a row of geometrical designs. Each side of the gate has a single rectangular niche.

Yet another temple, known as the Semi-Subterranean Temple, also has a sunken court which measures 28.5 metres by 26 metres and was accessed via a single staircase leading down into the court from the south side. The interior wall of this court also has stone heads protruding from it. In the centre of the court stelae or sculptures were found such as the 'Bennett Stela' which is 7.3 metres high and depicts possibly a ruler or High Priest of Tiwanaku. It is the tallest stone sculpture surviving from any ancient Andean culture. The figure is weeping and holds a beaker in one hand and a staff in the other. The figure is also covered in 30 small representations of animals and mythical creatures.

The Pumapunku was another temple mound, once again with a T-shape sunken court but this time the mound has only three tiers and is situated 1 km to the south-west of the main complex. The Pumpapunku is 150 square metres in area and 5 metres high. Unlike the Akapana mound there are stone portals with huge monolith lintels which functioned as a gateway to the whole sacred complex.

Residential Buildings

No storehouses or administrative buildings have been found at the site but there were large residential areas surrounding the sacred centre, these now lie under fields used for agriculture. These more humble structures were made using dried-mud bricks (adobe) and built on cobblestone foundations. There were also finer buildings in this area, elite residences with high adobe walls surrounding a coutyard and buildings constructed from finely-cut stone blocks. One of these buildings, known as the 'Palace of the Multicoloured Rooms', has walls which were painted in many coats over time in colours such as blue, green, red, orange and yellow. There are also canals, drainage channels, hearths, wall niches, and stone paved courtyards. Dedicated burial goods were excavated at the entrance to the building - gold, silver and turquoise jewellery, human remains, a llama foetus, pottery and bone tools.

Sculpture, Pottery & Textiles

Much of the sacred imagry at Tiwanaku can be found in other Andean cultures. The culture at Tiwanaku was influenced by its predecessors in the Titicaca basin, for example, the imagry of the Chavin and the architecture at Chiripa and Pukará. Repeated images at the site include the Staff Deity, severed trophy heads, and winged creatures (usually depicted in profile and running) with bird heads such as the condor and falcon. The Staff Deity appears on the famous Gateway of the Sun and is in typical pose: frontal holding a staff in each hand, rays coming from his head, a mask-like face, and wearing a tunic with kilt and belt. The image also appears on pottery and elsewhere in architecture and was likely the inspiration for the later worshipped Creator god Viracocha.

There are also several examples of large stone sculptures which the people of Tiwanaku may have intended to represent the first race of giants in pan-Andean mythology or former Tiwanaku rulers and priests. Some sculptures still have gold pins embedded in them suggesting fabric was used to dress them. They can also display traces of paint, indicating they were once brightly decorated. Other interesting sculptures from the site include a huge boulder sculpted into a model of a sacred precinct and the chachapumas, sculptures of puma-headed warriors who hold a knife in one hand and a severed human head in the other. These, along with the stone wall heads and finds of polished human skulls, strongly sugest a cult to the pan-Andean decapitator god. Other rituals are suggested by mass burials at the site such as one grave with 40 males, all with signs of being cut to pieces. The fact that the remains are buried in an area of rain-deposited sediment suggests that they were sacrificed after a catastrophic climate event.

Pottery finds include cups, bowls and jars with anthropomorhpic designs all with the distinctive orange base of Tiwanaku pottery. Distinctive shapes are the tall beakers and large storage vessels which were partially buried in pits. Many vessels show evidence of some degree of mass production using moulds. Most are brightly painted and gods, animals and geometric designs were a popular subject. Of particular note are vessels in the form of human heads, some capture precise idiosyncratic features and are, therefore, genuine portraits of a specific person or model. Tiwanaku pottery was exported throughout the empire and beyond via the large llama caravans used to connect Tiwanaku to its empire.

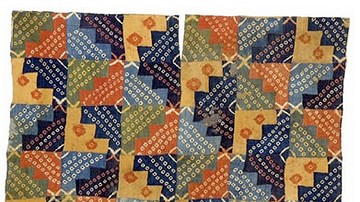

As with other Andean cultures, the residents of Tiwanaku were skilled weavers. Textiles rarely survive in the quantities of other more durable artefacts but enough examples are available to illustrate the skill and innovation of textile producers at the site. For example, a woollen tunic has flower decorations set in hard to achieve diagonal lines. Woollen hats from Tiwanaku have a distinctive box shape and are composed of five separately woven panels stitched together, sometimes with tassles added at the corners. Tiwanaku textiles use bright colours and the decorative motifs familiar from pottery - animals, birds, gods, and human figures - but these can appear in more abstract form and be squashed or stretched to suit the form of the object, especially in wall hangings and clothes. Geometric forms were also widely used in textile patterns, particularly the stepped diamond motif which is also seen in Tiwanaku architectural sculpture.

Collapse

The Tiwanaku empire collapsed around c. 1000 CE when faced with attacks from the Aymara Kingdoms, a collective group of states which included Colla, Lupaka, Cana, Canchi, Umasuyo and Pacaje. Tiwanaku the city was abandoned, possibly as late as c. 1100 CE, probably due to excessive drought brought about by regional climate change, but their monumental stone art and architecture survived to inspire the reverential Incas to similar artistic feats and they continue to impress the modern-day visitor with their timeless appeal.