The Townshend Acts were a series of acts passed by the Parliament of Great Britain between 1767 and 1768 to tax and regulate the Thirteen Colonies of North America. When the colonists considered the acts an abuse of power and protested them, Britain sent troops to enforce its mandates, thereby escalating the American Revolution (c. 1765-1789).

Origins

In the aftermath of the French and Indian War (1754-1763), as the North American theater of the Seven Years' War is often called, the victorious British Empire gained control of Canada and the territory between the Appalachian Mountains and the Mississippi River, previously held by France. However, with these new territories came a new set of problems; as colonial American settlers moved westward, they came into violent conflict with the displaced Native Peoples of North America. After one particularly destructive war known as Pontiac's Rebellion (1763-1764), the British Parliament decided additional measures would have to be taken to keep the peace in North America and resolved to dispatch a standing army of 10,000 regular soldiers.

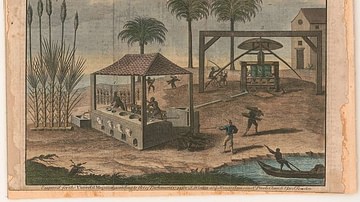

The upkeep of such an army would be expensive, however, and was estimated to cost around £200,000 per year. This was a price Parliament could ill-afford by itself since it was currently dealing with mountains of debt accumulated during the Seven Years' War. A new source of revenue would have to be found, and the eyes of Parliament soon turned to the Thirteen Colonies; after all, the funds were needed to provide for the colonies' own defense, so it seemed only right that the colonies footed part of the bill. On 5 April 1764, the ministry of Prime Minister George Grenville (l. 1712-1770) issued the Sugar Act, a tax on the molasses trade. This was met with outrage by colonial merchants since molasses made up a large part of the lucrative triangular trade with Europe and Africa and was important to the economies of the New England colonies.

But if the Sugar Act was protested mainly by colonial merchants, the Stamp Act, passed by the Grenville ministry the following year, sparked protest across all classes of colonists. The Stamp Act was the first direct tax imposed on the American colonies by Parliament and required the colonists to pay a tax on all paper materials, including legal documents, newspapers, marriage licenses, calendars, playing cards, and more. Anyone caught violating the act was to be tried by a vice-admiralty court appointed by the Crown rather than by a jury of their peers. The reason why the Stamp Act was so detestable to the Americans was because they felt that it violated their rights. Outspoken colonists like Samuel Adams (1722-1803) of Boston argued that when their ancestors crossed over to the New World, they retained the rights of Britons, including the right to tax themselves. Since the colonists were unrepresented in Parliament, they believed that any attempt by Parliament to directly tax them was a tyrannical abuse of power. Adams argued that if the colonists were to meekly accept a Parliamentary tax, they would be reduced from "the character of free subjects to the miserable state of tributary slaves" (Schill, 73).

In May 1765, the Virginia House of Burgesses issued the Virginia Resolves whereby it asserted that the colonists enjoyed the same rights as their English brethren and denied Parliament's authority to tax the colonies. This was followed in October by the Stamp Act Congress, a gathering of representatives of nine colonies in New York City, which echoed this sentiment in a Declaration of Rights and Grievances. However, the most consequential colonial protests took the form of street riots. On 14 August 1765, a large mob attacked the home of a stamp distributor in Boston, Massachusetts, and ransacked the house of Lt. Governor Thomas Hutchinson twelve days later. A similar riot broke out in Newport, Rhode Island on 27 August while across the colonies, royally appointed stamp distributors were intimidated into resigning by colonial mobs. These riots were celebrated by many colonists; indeed, a new group of political agitators, the Sons of Liberty, proudly dated the founding of their organization to the August riots.

The Stamp Act was ultimately repealed in March 1766; this was largely due to British merchants, who had become frustrated that the act had interfered with their ability to collect debts from their American counterparts and lobbied for its repeal. The Sugar Act was likewise replaced with a less burdensome tax. However, this did not mean that Parliament was backing down. While Parliament agreed that the Americans enjoyed the same rights as Britons, it maintained that the colonists were no different from the majority of Britons who owned no land and could not vote but were nevertheless virtually represented in Parliament. To cement this claim, Parliament passed the Declaratory Act in 1766, which stipulated that Parliament had the power to make laws for all colonies across the vast British Empire "in all cases whatsoever" (Middlekauff, 118). Many interpreted this to include taxation.

Charles Townshend

In July 1766, King George III of Great Britain (r. 1760-1820) elevated the elder William Pitt (l. 1708-1778) to the peerage as the Earl of Chatham and invited him to form a ministry. Although Chatham had been an outspoken supporter of the American cause during the Stamp Act debate, the onset of an illness prevented him from interfering when his Chancellor of the Exchequer, Charles Townshend, introduced a new set of taxes on the Thirteen Colonies. Brilliant yet often unpredictable, Townshend remained steadfast in his desire to increase the authority of royal officials in the colonies and to make them independent of popular influence from the unruly colonists. In 1767, as Chatham's illness kept him aloof from Parliament, Townshend spearheaded the acts that would bear his name, including:

- The Revenue Act of 1767: a tax on glass, lead, paint, paper, and tea. It also gave customs officials permission to search private property for smuggled goods. Passed on 29 June 1767.

- The Commissioners of Customs Act of 1767: established a Board of Customs Commissioners for the colonies. Headquartered in Boston and consisting of five commissioners, this was supposed to enforce regulations and ensure the collection of taxes. Passed on 29 June 1767.

- New York Restraining Act of 1767: forbade the legislature or governor of New York from passing any new bills until the colony agreed to feed, house, and supply the British soldiers stationed there. This was passed after the Province of New York refused to house British soldiers, as was required under the Quartering Act of 1765. Passed on 2 July 1767.

- Indemnity Act of 1767: reduced taxes on the British East India Company when it imported tea to England, allowing the Company to re-export the tea to the colonies at a cheaper price, where it would then be sold to the colonists. Passed on 2 July 1767.

- Vice Admiralty Court Act of 1768: stipulated that smugglers and other violators of the acts were to be tried by admiralty courts appointed by the Crown rather than by juries of their peers. New admiralty courts were set up in Boston, Philadelphia, and Charleston. This act is often included with the others, although Townshend himself did not suggest it. Passed on 8 March 1768.

With the five Townshend Acts, Parliament effectively doubled down on its right to tax the colonies, citing the Declaratory Act of 1766 as its justification. Charles Townshend died suddenly on 4 September 1767 and did not live to see the colossal impact his acts had on the relationship between Britain and its colonies.

Massachusetts Circular Letter

In the colonies, any semblance of celebration that had accompanied the repeal of the Stamp Act dissipated when news of the Townshend Acts reached them. The immediate response to the acts was unease, frustration, and confusion as the colonists debated whether the Townshend Acts violated their rights. This question was answered by John Dickinson (1732-1808), a Pennsylvanian lawyer who penned a series of twelve essays between 1767 and 1768 that were collectively titled Letters from a Farmer in Pennsylvania. Under the pseudonym "A Farmer," Dickinson argued that while Parliament had the right to regulate trade, it had no constitutional right to levy taxes for revenue on the colonies. Dickinson warned that the Townshend Acts were there to test the colonists' disposition and, if the colonists were to accept them, would mark "a dire foreteller of future calamities" (Middlekauff, 162).

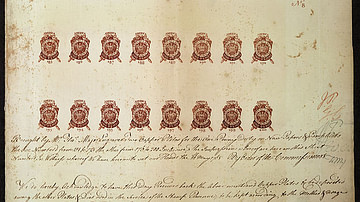

Dickinson's letters put into words what many Americans were fearing and galvanized the resistance to the Townshend Acts; for this reason, some historians consider Dickinson's letters the most impactful colonial writing of the Revolutionary era before the publication of Thomas Paine's Common Sense in 1776. Dickinson's reasoning certainly resonated with James Otis Jr. (1725-1783) of Boston, who, along with Samuel Adams, drafted a letter that condemned the Townshend Acts as unconstitutional and urged all colonial legislatures to petition the king to repeal it. Otis and Adams' letter was approved by the Massachusetts House of Representatives, who sent it on to the other colonial assemblies; the letter became known as the Massachusetts Circular Letter. In April 1768, Lord Hillsborough, the newly appointed Secretary of State for the Colonies, ordered the Massachusetts House of Representatives to revoke the Circular. The House voted 92-17 against doing so, and the representatives who voted against rescinding the Circular were celebrated throughout the colonies as the "Glorious Ninety-Two."

Interpreting this as sedition, Hillsborough ordered Governor Francis Bernard of Massachusetts to dissolve the House of Representatives and sent similar orders to other colonial governors to dissolve their own assemblies if the assemblies accepted the Circular Letter. If Lord Hillsborough believed that this was enough of a threat to calm things down, he was mistaken; the Virginia House of Burgesses not only approved the Massachusetts Circular but issued a circular of its own, calling on all colonies to unite against any British actions that "have an immediate tendency to enslave them" (Middlekauff, 167). The Massachusetts and Virginia circulars were approved by the assemblies of New York, New Jersey, Maryland, Connecticut, Delaware, North Carolina, South Carolina, and Georgia, leading to the assemblies' dissolutions by their colonial governors.

Boycotts

As the legislatures issued remonstrances against the Townshend Acts, colonial merchants banded together to boycott British goods. Such boycotts had succeeded two years earlier when the depressed trade with their American counterparts pressured British merchants into lobbying for the Stamp Act's repeal, and colonists hoped for the same outcome this time. Once again, Boston took the lead; in October 1767, several Bostonian merchants made a nonconsumption agreement whereby they agreed to boycott a list of British imports. Boston's example was soon followed by the merchants of New York, who agreed to close their harbors to British imports until the Townshend Acts were repealed. In Virginia, a boycott on several imports, including slaves, was spearheaded by George Washington (1732-1799) and his neighbor George Mason (1725-1792). Because the House of Burgesses had been dissolved by Virginia's governor, the former burgesses gathered as private citizens in the Williamsburg home of Andrew Hay, where they once again denounced the Parliamentary taxes as unconstitutional and approved a nonconsumption agreement of their own. By 1769, merchants from across the colonies had made similar pledges.

Although British trade did take a hit from these boycotts, they were not as effective as they could have been since many colonial merchants did not participate. Still, many other colonists embarked on boycotts of their own, refusing to purchase British goods. Many colonists refused to drink British-imported tea, and more women participated in spinning bees, public events in which they would gather to make homespun clothes. Small-scale manufacturers of clothing and other household articles began popping up across the colonies as the Americans already sought to move away from their economic dependence on Britain.

The Liberty Affair

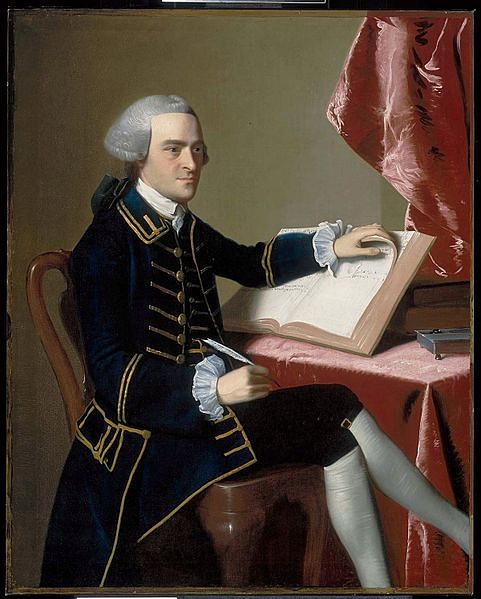

On 5 November 1767, the five British customs commissioners arrived in Boston, which was to be their headquarters as stipulated by the Commissioners of Customs Act. Their job was to ensure the collection of taxes and enforcement of regulations, but it immediately became clear that this would not be an easy task. The commissioners had the misfortune of arriving in Boston on Guy Fawkes' Day, which would have been a riotous day in the city even without the added tensions of the Townshend Acts; as it happened, the commissioners were greeted by drunken crowds carrying effigies and wearing labels that read "Liberty & Property & no Commissioners" (Middlekauff, 163). Nor did the commissioners receive a warm welcome from Boston's leading citizens. John Hancock (1737-1793), one of the city's wealthiest merchants, snubbed the commissioners by refusing to allow his Cadet Company, a military organization he ran, to participate in a welcome parade organized by Governor Bernard. Hancock also prevented his company from attending a public dinner hosted by the governor once it became known that the commissioners would be in attendance.

While Hancock's contempt of the commissioners earned him the support of the public, he soon became a target for the royal officials themselves, who hoped to make an example out of him. On 9 May 1768, a sloop belonging to Hancock called the Liberty returned from a trip to Madeira, carrying crates of Madeira wine for Hancock's own use. Two customs collectors boarded the vessel to check for contraband goods but reported no wrongdoing. However, on 10 June, one of these officials, Thomas Kirk, came forward and claimed that he lied in his initial report. Kirk claimed that he had been forcibly detained below decks on the Liberty as the crew unloaded its smuggled cargo and that the captain of the sloop threatened him with violence if he did not keep silent. Kirk's doubtful report was all the pretext the commissioners needed to seize the Liberty.

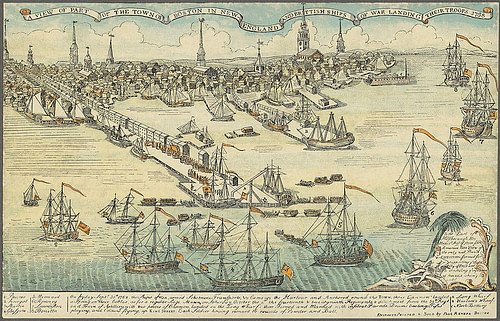

The task of taking the Liberty away fell to the crew of the HMS Romney, a 50-gun man-of-war, but when sailors from the Romney arrived to take possession of the sloop, they were met by a mob of angry Bostonians, and a brawl broke out. No one was seriously injured, and the British sailors succeeded in taking control of the Liberty. However, the incident only encouraged more rioting and by nightfall, a crowd of several thousand Bostonians marched through the streets. The mob hunted down customs officials, beat them when they caught them, and ransacked the houses of officials who escaped their grasp. Things got so bad that the customs officials had to withdraw to Castle William, a fortification on Castle Island in Boston Harbor.

In the aftermath of the Liberty riots, John Hancock was prosecuted in a highly publicized five-month trial before a vice-admiralty court. He was represented by John Adams (1735-1826), who eventually managed to get all charges against Hancock dropped. Despite the positive outcome for Hancock himself, the city of Boston was about to face an entirely new ordeal. In response to Boston's rioting, Lord Hillsborough authorized General Thomas Gage, commander-in-chief of the British forces in North America, to send troops to Boston to keep the peace. On 1 October 1768, the first elements of the British 29th and 14th regiments arrived in Boston Harbor, escorted by warships commanded by Commodore Samuel Hood. The red-coated soldiers marched through the city with fixed bayonets, a not-so-subtle warning to the unruly colonists. Tensions between the British soldiers and the Bostonians would rise over the coming months, ultimately culminating in bloodshed with the Boston Massacre on 5 March 1770.

Partial Repeal

In April 1770, the new British ministry under Lord North sought to ease tensions in the colonies. To this end, Parliament approved a bill that repealed all the Townshend Acts except for one: a tax on tea. Lord North insisted on keeping the tax on tea in order to remind the Americans that Parliament indeed had authority over the colonies in all respects, including taxation. Therefore, even though Parliament had been forced to repeal the Stamp Act and most of the Townshend Acts, the core issue remained unresolved.

The Townshend tax on tea soon led to the Tea Act of 1773, which allowed the British East India Company to ship tea directly to the colonies. This resulted in the Boston Tea Party, which, in turn, led to the Intolerable Acts and the Battles of Lexington and Concord (19 April 1775). The Townshend Acts, therefore, played an important role in worsening the relations between Britain and the colonies and paving the way for the American Revolutionary War (1775-1783) and the independence of the United States of America.