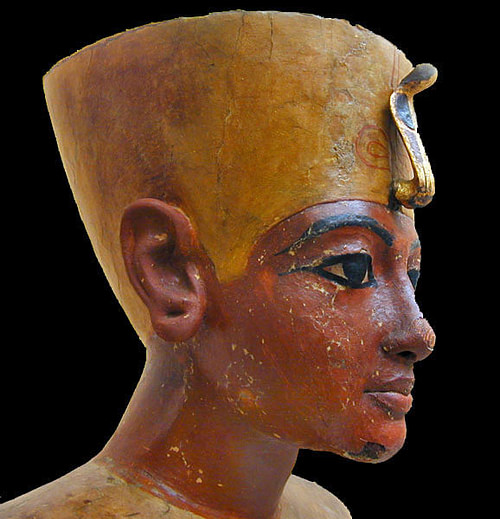

Tutankhamun (also known as Tutankhamen and `King Tut', r. c.1336-c.1327 BCE) is the most famous and instantly recognizable Pharaoh in the modern world. His golden sarcophagus is now a symbol almost synonymous with Egypt. His name means `living image of [the god] Amun'.

He was born in the year 11 of the reign of Pharaoh Amenhotep IV (better known as Akhenaten, r. 1353-1336 BCE) c. 1345 BCE and died, some claim mysteriously, in c.1327 BCE at the age of 17 or 18. He became the celebrity pharaoh he is today in 1922 when the archaeologist Howard Carter discovered his almost-intact tomb in the Valley of the Kings.

While it was initially thought that Tutankhamun was a minor ruler, whose reign was of little consequence, opinion has changed as further evidence has come to light. Today Tutankhamun is recognized as an important pharaoh who returned order to a land left in chaos by his father's political-religious reforms and who would no doubt have made further impressive contributions to Egypt's history if not for his early death.

Tutankhamun's Youth & Rise to Power

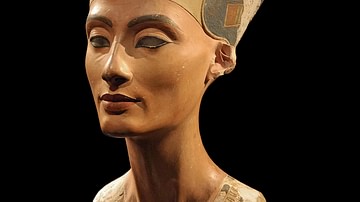

Tutankhamun's father was Amenhotep IV of the 18th Dynasty of Egypt whose wife, Nefertiti, is as equally famous and recognizable as her step-son. Tutankhamun's mother is thought to have been the Lady Kiya, one of Amenhotep's lesser wives, and was not Nefertiti (though this is a common misconception). It has also been suggested that Tutankhamun was the son of Amenhotep III (r.c. 1386-1353 BCE) and his queen Tiye (l. 1398-1338 BCE) but most scholars reject this theory. His mother is not mentioned in any inscriptions and so her identity is unknown. Egyptologist Zahi Hawass has noted that most scholars believe Kiya was Tutankhamun's mother "but the balance of opinion may yet change" (49).

Amenhotep III ruled over a land whose priesthood, centered on the god Amun, had been steadily growing in power for centuries. By the time Amenhotep IV came to power, the priests of Amun were on almost equal standing with the royal house in terms of wealth and influence. In either the 9th or the 5th year of his reign, Amenhotep IV outlawed the old religion, closed the temples, and proclaimed himself the living incarnation of a single, all-powerful, deity known as Aten.

He moved his seat of power from the traditional palace at Thebes to one he built at the city he founded, Akhetaten (`The Horizon of Aten', later known as Amarna) and proceeded to concentrate on his new religion, often to the detriment of the people of Egypt. Akhenaten's religious reforms, and their impact during his reign, would also define the later rule of his son.

Tutankhamun was named Tutankhaten (`living image of Aten') when he was born and, while still a child, was engaged to the fourth daughter of Nefertiti and Akhenaten, his half-sister Ankhesenpaaten (`her life is from Aten' or `her life is of Aten'). Ankhesenpaaten must have been older than Tutankhaten, however, as she was previously married to her father and may have had a daughter by him.

The historian Margaret Bunson claims she was five years older than Tutankhaten citing inscriptions which indicate she was thirteen when her half-brother took the throne at age eight (23). It is believed that the Lady Kiya (or his unknown mother) died early in Tutankhaten's life and he lived with his father, step-mother, and half-siblings in the palace at Amarna. Zahi Hawass writes:

The two children must have grown up together and perhaps playing together in the palace gardens. The royal children would have had lessons from teachers and scribes, who would have given them instruction in wisdom and knowledge about the new religion of the Aten. It is likely that Akhenaten wanted his children to continue with the worship of Aten, not to go back to the old religion dedicated to Amun...Tutankhaten and Ankhesenpaaten would probably have been married to one another at a very young age, almost certainly for reasons of state, but perhaps they also loved one another. To judge from their portrayal in the art that fills the golden king's tomb, this was certainly the case. We can feel the love between them as we see the queen standing in front of her husband giving him flowers and accompanying him while he was hunting. (51)

Tutankhaten came to the throne upon the death of his father in c. 1336 BCE at the age of eight or nine. Miniature symbols of royalty (such as the crook and flail, royal staff) were found in his tomb and it seems likely he played with these as a young child as he was being groomed for future rule. Hawass writes, "A number of these [items] were inscribed with his birth name, demonstrating that he was crowned as Tutankhaten" (51).

Between the death of Akhenaten and the ascent of Tutankhaten there was an interim pharaoh named Smenkhkare about whom little is known. It has been suggested, however, since Smenkhkare's throne name was identical to that of Akhenaten's coregent, that this pharaoh was Nefertiti who ruled while Akhenaten's health may have been in decline and Tutankhaten was still too young to assume the throne (Hawass, 47).

Nefertiti seems to have assumed the male persona of `Smenkhkare' as ruler in order to avoid the same kinds of problems which arose after the death of the female pharaoh Hatshepsut (r. 1479-1458 BCE) centuries earlier when, in an effort to restore harmony to the land (since females were not supposed to rule) her successor Tuthmosis III (r. 1458-1425 BCE) had her name and memory erased from all public monuments and stele. Smenkhkare died two years into his (her) reign and Tutankhaten was crowned king.

Tutankhaten Becomes Tutankhamun

Early in his reign, Tutankhaten either decided for himself (or, more probably was forced) to return Egypt to the old religious practices which his father had outlawed and suppressed. Hawass explains:

His advisors, clearly with the support of the priests of Amun, either convinced or forced the young king once again to give Amun his place as the universal god of Egypt and abandon the cult of the Aten. The name of the child-pharaoh was changed from Tutankhaten to Tutankhamun, and his queen became Ankhsenamun. At some point, the court left Amarna, and Tutankhamun and Ankhsenamun took up primary residence at the traditional capitals of Thebes and Memphis. A stele from the young king's reign called the Restoration Decree of Tutankhamun describes a country in chaos at the death of Akhenaten. It tells us that the cults of the gods had been abolished, their temples abandoned, and that as a result they no longer heard the prayers of the people. Tutankhamun claims to have carried out repairs on the derelict temples and put things back to rights. (54)

The ideal of ma'at, universal harmony, was the most important spiritual concept in ancient Egypt. It was believed that the land of Egypt was a mirror image of the celestial land and individuals had a responsibility to behave in a certain way on earth to keep balance with the higher realm. By abandoning the old gods and the ancient practices, Akhenaten would have upset this balance and destroyed the harmony between the people and their gods.

When the people were forced to abandon their gods, it was thought, the gods abandoned the people. Tutankhamun's reforms, then, would have had an immense impact on the people of Egypt with his restoration of universal harmony. The temples were rebuilt and the priests who had hidden the iconography and texts relating to the old religion brought them back to their rightful places.

With balance restored, Tutankhamun turned his attention to rule and to those activities befitting a king such as horseback riding, hunting, training in military skills, and enjoying leisure time with his young wife (Hawass, 54). The historian Barbara Watterson writes, "He was said to be a king who `spent his life making images of the gods', and it was during his reign that work on the colonnade in Luxor Temple with its superb scenes of the Opet Festival, was undertaken" (112-113). Tutankhamun also officiated at the Opet Festival with his queen and commissioned his treasurer to carry out a fiscal inspection of all the temples of the land. The palace at Thebes which he shared with Ankhsenamun:

...would have been built of mud brick and beautifully painted. It would have consisted of many large rooms and columned halls surrounded by smaller suites of rooms. The largest of these would have contained a series of larger halls leading to a throne room. These would have been decorated with lively scenes of birds and natural motifs. There would have been gardens and pools, all designed to soothe and delight the royal eyes and ears. (Hawass, 55)

Even though balance had been restored and temples and palaces rebuilt, Egypt was still recovering from the disorder Akhenaten had plunged the country into. Hawass writes, "By the reign of Tutankhamun the situation in the Near East had changed drastically since the golden days of the Egyptian empire" (56). The army, whose training and equipping had been neglected by Akhenaten, was no longer the effectual fighting force it had been under the reign of Tutankhamun's grandfather Amenhotep III. The commander of the army, Horemheb (r. 1320-1292 BCE), who was held in high regard as one of Tutankhamun's chief advisors, was repeatedly unsuccessful in his campaigns against the Hittites. Egypt failed to regain Kadesh and also lost a number of other vassal states.

The Hittites grew more powerful as Tutankhamun struggled to restore Egypt to its former glory and, no longer having to fear intervention from the Egyptian military, the Hittites destroyed the kingdom of the Mitanni, who had formerly been an ally of Egypt. It should be kept in mind that Tutankhamun, at this time, was around the age of 16 and was tasked with the enormous responsibility of revitalizing the country his father had single-handedly devastated.

Even with the help of the elder counselors who surrounded him, the teen-age king must have found his position daunting but, still, he seems to have done his best to redeem the country's present from its recent past. What he might have accomplished in a longer reign will never be known as he died before reaching the age of twenty.

Tutankhamun's Death & Aftermath

The death of the young king has been called `mysterious' for centuries but there really is no mystery involved. Many people died young in the ancient world just as many do in the present day. The damage to Tutankhamun's skull, which early historians cited as proof that he was murdered, has come to be understood as the work of the embalmers who removed the brain. The injuries to the body of the skeleton are the result of its removal from the sarcophagus during the 1922 excavation when the head was removed from the body and the skeleton was violently pried loose because it was stuck to the bottom of the sarcophagus with resin.

It has also been speculated that Tutankhamun died of an untreated abscessed tooth or infection from a broken leg but these theories have also been disproved. Another theory is that Tutankhamun was the product of an incestuous union and so was simply not genetically disposed to a long life. Historians who support this theory point to the two children of Tutankhamun and Ankhsenamun who were both stillborn (their mummies were buried with their father and discovered in his tomb) as physical evidence of the incestuous practices of Egyptian royalty of the 18th dynasty. Whether Akhenaten and Kiya were related, however, is not known and so this theory also cannot be confirmed. All that is clearly known is that Tutankhamun died in January of 1327 BCE and that his death was unexpected as evidenced by the hasty construction of his tomb. Hawass notes:

The country would have fallen in disorder at the sudden death of Tutankhamun, who left the land with no heir. At the moment of his death, it is possible that Egypt was engaged in battle with the Hittites, in which case it is likely that Horemheb, who might otherwise have been expected to take the throne, was in the north leading the troops. Another high official, [named] Ay, supervised the king's trip to the afterlife instead. Ay bore the titles of Commander of Chariotry and Fanbearer at the King's Right Hand...By burying Tutankhamun, Ay proclaimed himself the next king. (58-61)

Ankhsenamun was now expected to marry Ay (r. c. 1324-1320 BCE) in order to ensure the continued balance of the land but she clearly had other ideas. She wrote to the Hittite king Suppiluliuma I (r. 1344-1322 BCE) for help:

My husband has died and I have no son. They say that you have many sons. You might give me one of your sons and he might become my husband. I would not want to take one of my servants. I am loath to make him my husband. (Hawass, 67)

While Egyptian pharaohs often married foreign women, it was unheard of for an Egyptian woman, especially one of royal blood, to marry a foreigner. This would have been as much an affront to universal harmony as Akhenaten's reforms had been. In fact, it was a long-standing practice in Egypt to refuse to send women as wives to foreign countries and this would have been understood by Ankhsenamun even as she wrote her letters. That she would make this gesture, in defiance of tradition and the concept of ma'at, shows her desperate circumstances but why, exactly, she was so desperate is not clear.

The letters of Ankhsenamun, however, have been cited by those who support the theory that Tutankhamun was murdered by Ay or through a plot involving both Ay and Horemheb. The Hittite king was more than happy to oblige Ankhsenamun and sent one of his sons, Zananza, to Egypt; but the prince never arrived. He was killed at some point before reaching Egypt's borders and it has long been suggested that this was the work of Horemheb and, perhaps, Ay. Whether Ankhsenamun married Ay is not known. She disappears from the historical record after the incident with the Hittite king.

Ay ruled Egypt for three years and died without an heir. Horemheb then took the throne. As he was not of royal blood, he needed something to legitimize his reign and he chose religion as the most effective means in this. Claiming that he had been chosen by the god Horus of Hutsenu to restore Egypt to prominence and glory, he instituted a program of return to orthodox religious practices. He destroyed all public records and monuments erected by Akhenaten and erased the memory of Tutankhamun.

Hawass points out that, "He tried, in fact, to erase all evidence of Akhenaten and his immediate successors from the pages of history" (69). Horemheb would rule Egypt for the next 27-28 years and, in that time, did return Egypt to its former status as a great power. Tutankhamun's tomb was accidentally buried when workmen built the later tomb of Ramesses VI (r. 1145-1137 BCE) and his name was forgotten until Howard Carter and his team discovered the site in 1922.

The tomb was broken into twice during the reign of Ay and resealed and then, because Horemheb had erased Tutankhamun's name from the records and it had become buried, the tomb was overlooked by grave robbers and remained intact until its discovery in the 20th century. Hawass writes, "By effectively wiping the name of Tutankhamun from the annals of the pharaohs, Horemheb actually succeeded in insuring that the name of the golden king would resound through the corridors of time" (69).

The treasures from the tomb of Tutankhamun have regularly drawn crowds in Egypt and also whenever they have gone on exhibit outside of their present home at the National Museum in Cairo. Prior to the tomb's discovery, the most famous ruler of ancient Egypt was probably Cleopatra VII, Nefertiti, or Ramesses the Great but, since 1922, it has been Tutankhamun.

Tutankhamun's Enduring Fame

His fame rests mainly on the magnificent artifacts found in his tomb and the sensational discovery (which was headline news worldwide) on 4 November 1922. The `Mummy's Curse', or `Curse of Tutankhamun', has only amplified his celebrity. The curse myth comes from a misinterpretation of an inscription found in the tomb. In the 1920's, the inscription was thought to read: “I will kill all of those who cross this threshold into the sacred precincts of the royal king who lives forever.” This was found on the door of the treasury room in Tutankhamun's tomb.

The 1922 translation has been found to be wrong, however, and the inscription actually reads, “I am the one who prevents the sand from blocking the secret chamber” (the `I' in the sentence referencing the door and the spirits which would have been invoked to keep the door sealed). The curse myth spread quickly and seemed corroborated by an event which took place a few months after the tomb was opened.

The English Lord Carnarvon, who funded Carter's excavation, died `mysteriously' on 6 May 1923 and the international press seemed intent on ascribing his death to the tomb's opening and this ancient curse. After Carnarvon, the death of anyone who was in any way involved in opening the tomb was blamed on the curse. Regarding this, Hawass writes:

In fact, there were no real mysteries surrounding the death of Carnarvon. He died of blood poisoning triggered by [an] infected mosquito bite, which he had cut open with his razor while shaving…the mortality rate of the people most closely associated with the tomb was very low. Arthur Mace died in 1928, but he had been sickly for a long time. Carter himself lived until 1939, Breasted died in 1935; Lucas died in 1945; Gardiner lived until 1963; and Lady Evelyn died in 1980 at the age of seventy-nine. (146)

The curse, which was never a curse to begin with, is still associated with Tutankhamun and this, along with the story of the discovery of his tomb and its splendor, has made his name famous around the world and kept his memory alive. Unfortunately, this focus on the curse and the tomb's artifacts has obscured the very real accomplishments of Tutankhamun during his short reign; accomplishments made all the more impressive when one considers the young age of the king at the time of his death.