Tyrian purple (aka Royal purple or Imperial purple) is a dye extracted from the murex shellfish which was first produced by the Phoenician city of Tyre in the Bronze Age. Its difficulty of manufacture, striking purple to red colour range, and resistance to fading made clothing dyed using Tyrian purple highly desirable and expensive.

The Phoenicians gained great fame as sellers of purple and exported its manufacture to its colonies, notably Carthage, from where it spread in popularity and was adopted by the Romans as a symbol of imperial authority and status.

Manufacture

In Phoenician mythology, the discovery of purple was credited to the pet dog of Tyros, the mistress of Tyre's patron god Melqart. One day, while walking along the beach the couple noticed that after biting on a washed up mollusc the dog's mouth was stained purple. Tyros asked for a garment made of the same colour and so began the famous dyeing industry.

The first historical record of the dye is in texts from Ugarit and Hittite sources, which indicate that the manufacture of Tyrian purple began in the 14th century BCE in the eastern Mediterranean. Cloth dyed with Tyrian purple was a hugely successful export and brought the Phoenicians fame throughout the ancient world. Indeed, some historians (but certainly not all) claim that the very name Phoenicia derives from the Greek word phoinos meaning 'dark red' which refers to the dye and may itself be a translation of the Akkadian word for both Canaan and red, kinahhu. Despite their formidable reputation, the dyers of Tyre did not have a monopoly on the process even in the Late Bronze Age as four Linear B tablets from Knossos indicate that it was manufactured (albeit on a small scale) on Minoan Crete too, which also had a supply of the shellfish in its coastal waters.

The dye was extracted from the fluid of the Murex trunculus, Purpura lapillus, Helix ianthina, and especially the Murex brandaris shellfish. Living in relatively deep water, these shellfish were caught in baited traps suspended from floats. The dye was then extracted from the glands of thousands of putrefied crushed shellfish left to bake in the sun. The resulting liquid was used to dye cloth fibres in manipulated variations of colours ranging from pink to violet. One can imagine the smell from the process must have been overwhelming and perhaps explains why Sidon's workshop was 14 kilometres south of the city at Sarepta.

In his Natural History the Roman writer Pliny the Elder describes how the dye extraction process had by then developed. Taking three days, salt was added to the mash of shellfish glands which was then boiled down in tins. Finally, whole fleeces were dipped into the mixture when the correct hue had been reached. Fibres were dyed before weaving them into clothes and only very rarely would completed garments have been dyed; perhaps very valuable ones might have been redyed.

According to the historian B. Caseau, "10,000 shellfish would produce 1 gram of dyestuff, and that would only dye the hem of a garment in a deep colour" (Bagnall, 5673). These numbers are supported by the quantity of discarded shells which, at Sidon for example, created a mountain 40 metres high. Such figures also explain why the dye was worth more than its weight in gold. In a 301 CE price edict from the reign of Roman emperor Diocletian, we learn that one pound of purple dye cost 150,000 denarii or around three pounds of gold (equal to around $19,000 at the time of writing). A pound of pre-dyed wool would set you back one pound of gold.

Such was the demand for Tyrian purple that vast deposits of the shells have been excavated on the outskirts of Sidon and Tyre and the species was all but driven to extinction along the coasts of Phoenicia. The Phoenicians not only exported the dyed cloth but also the process of extracting the dye, as indicated by the shell deposits found at Phoenician colonies across the Mediterranean. Carthage was particularly involved in its manufacture and continued to spread its fame into Roman times and the Byzantine period. In antiquity, besides the Phoenician cities and Carthage, other known manufacturing centres included Rhodes, Lesbos, Motya (Sicily), Kerkouane (North Africa) and various other places in Asia Minor and southern Italy.

Tyrian purple was always the finest on the market as the Phoenicians (and through inheritance perhaps also the Carthaginians) not only had access to the raw material but years of experience. They were expert at blending different species of shellfish in certain sequences of the process and adding extra secret ingredients so that only they could produce the most prized colour of all, a rich deep purple which seemed crimson when held to the light. Tyrian purple was also noted for its great durability and lack of fading. As with any luxury product, there were cheaper, if less effective, alternatives to the real thing. Purple could be produced from certain lichens or first dyeing using red (madder) and then overdyeing using blue (woad). The Gauls used whortleberry to die textiles purple, which were, ironically, then made into clothes for slaves.

Uses

The primary function of Tyrian purple was to dye textiles, especially clothing. The highest quality cloth was known as Dibapha, meaning 'twice dipped' in the purple dye. Because of the time-consuming production process, the huge number of shells required, and striking colour range of finished articles, such dyed textiles were, of course, a luxury item. As a consequence, Tyrian purple became a status symbol representing power, prestige and wealth. The high value of purple cloth is further indicated by its presence on tribute lists alongside other precious goods such as silver and gold which Tyre was obliged to pay to the Assyrian kings in the 9th and 8th centuries BCE. Alexander the Great, too, was said to have come across 5,000 talents in weight of purple cloth at Susa, likely acquired through tribute and kept as a permanent deposit of high value. The still bright colour 180 years after its manufacture did much to enhance the already formidable reputation for the durability of Tyrian purple cloth.

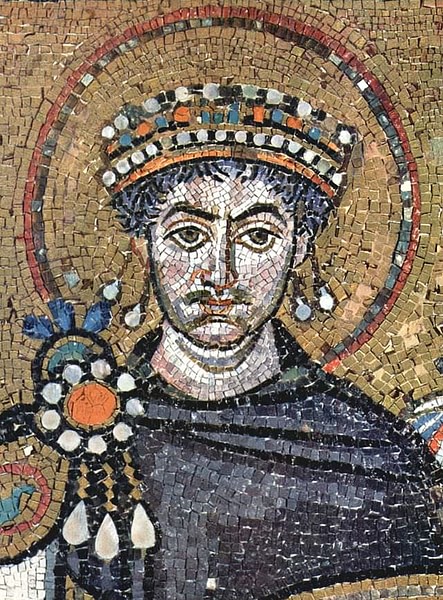

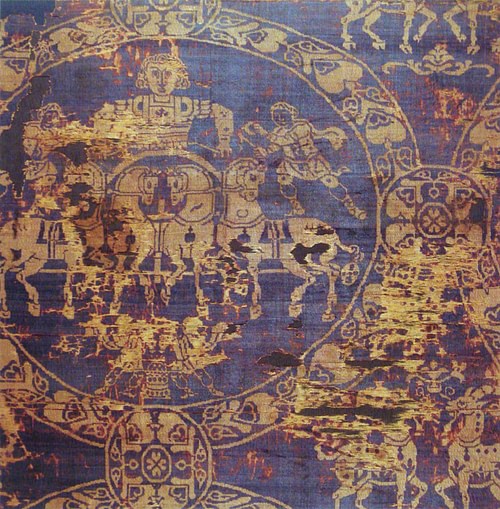

The status-conscious Romans were particularly fond of purple garments and reserved them for the elite only. The imperial family, magistrates and some elites were permitted to wear the toga praetexta which had a purple border, and generals who celebrated a Roman Triumph could wear on their big day the toga picta which was entirely purple with a gold border. In time, the colour purple came to represent the emperor, although it was Julius Caesar who first wore the all-purple toga purpurea. By the 5th century CE purple and silk formed a winning combination, and its production became a state monopoly from the reign of Alexander Severus (222 - 235 CE). Only the emperor could wear these silk garments (kekolumena) or those lucky enough to be given his favour, and no foreigner was permitted to purchase them. Emperors were even depicted wearing Tyrian purple, too, such as the celebrated mosaic portrait of Justinian I in the Basilica of San Vitale, Ravenna. Purple was long associated with the priesthood from Roman times onwards, and it was not until 1464 CE that Pope Paul II ordered the replacement of purple robes with scarlet ones for Church vestments.

It is thought that such was the symbolism of purple in ancient Rome that even imperial monuments and sarcophagi came to include it in the form of porphyry marble which has a deep and uniform purple colour. Besides textiles, Tyrian purple was sometimes used to dye parchment and several examples of Late Antiquity texts dyed purple survive, such as the Codex Rossano.