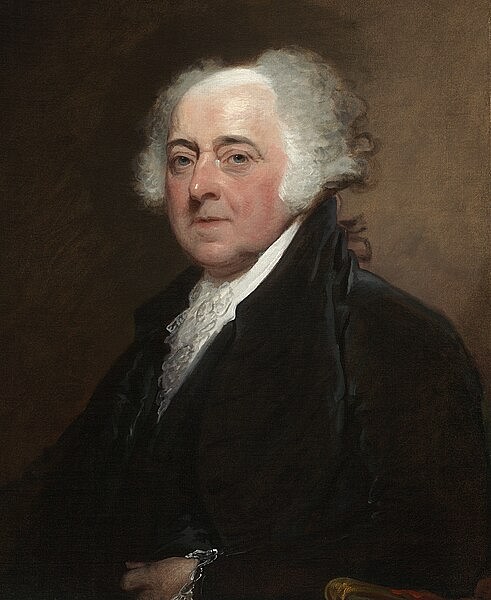

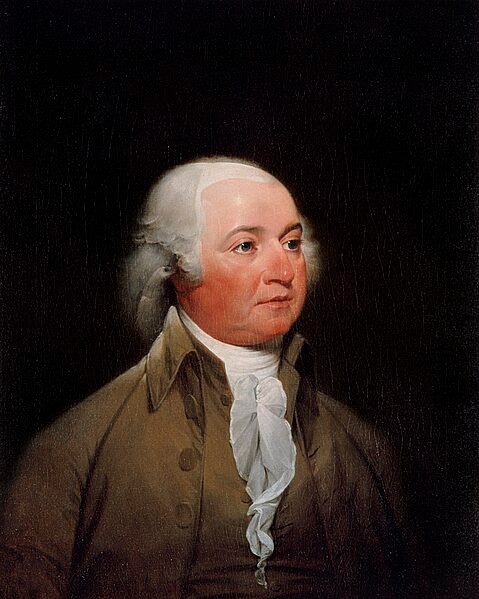

The US presidential election of 1796 was the first contested presidential election in the history of the United States. John Adams, the candidate of the Federalist Party, won the presidency, defeating his rival, Thomas Jefferson, candidate of the Democratic-Republican Party. Since Jefferson won the second most votes, he became Vice President, as was the protocol at the time.

In the previous two national elections – the US presidential election of 1789 and 1792 – George Washington had been unanimously voted into office, and the presidency had never seriously been contested. Now, with Washington declining to serve a third term, each political party scrambled to secure support for its candidate. Adams, as the incumbent vice president, was widely viewed as Washington's natural successor, but his association with the haughty, nationalist Federalists led to accusations that he was a pro-British monarchist. Jefferson, likewise, was attacked for his party's support of the bloody French Revolution, and his hypocritical opinions on slavery were brought into question. The use of partisan newspapers to attack the candidates became prevalent in this election, reflecting the increase of factionalism in US politics.

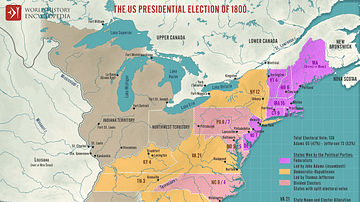

At the time, presidential elections were conducted very differently than they are today. Candidates did not run on a shared ticket; instead, each member of the Electoral College cast two votes for whichever candidates they pleased. The candidate who got the most votes was elected president, while the candidate with the second most votes became vice president, regardless of political party. It was for this reason that Adams ended up winning the presidency with Jefferson as his vice president, even though they had been rivals in the election. The partisanship that fueled this election would only worsen four years later, when Adams and Jefferson rematched in the US presidential election of 1800.

Background: Washington's Farewell Address

It was less than two months before the election, on 19 September 1796, when President Washington's famous Farewell Address appeared in the Philadelphia newspaper American Daily Advisor, confirming that he would not seek a third term in office. In the address, Washington revealed that he had initially planned on retiring after his first four years in office but had decided to serve a second term because of heightening tensions with Great Britain. Now, with that crisis averted, Washington saw no reason to stick around and was happy to hand the torch off to a successor. He then went on to emphasize the importance of the Union, which bound all Americans together and protected their liberties, before warning against three existential dangers that threatened to destroy that Union: regionalism, partisanship, and foreign entanglements. On the issue of political partisanship – or 'factionalism' as it was then known – Washington warned that it would lead to a 'spirit of revenge' and would open the door to 'foreign influence and corruption'. He went on to say:

[Political parties] serve to organize faction, to give it an artificial and extraordinary force; to put, in the place of the delegated will of the nation the will of the party, often a small but artful and enterprising minority of the community…they are likely, in the course of time and things, to become potent engines, by which the cunning, ambitious, and unprincipled men will be enabled to subvert the power of the people and to usurp for themselves the reins of government, destroying afterward the very engines which have lifted them to unjust dominion.

(constitutioncenter.org)

Political Parties: Federalists vs. Democratic-Republicans

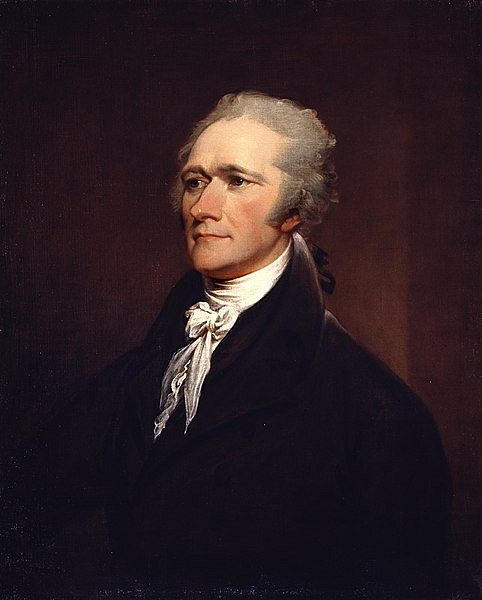

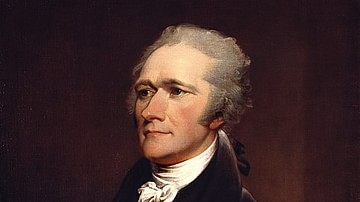

Indeed, the outgoing president had every reason to fear the rise of factionalism, as for the first time, political parties were developing in American politics. The first of these parties – and the one with which Washington himself most aligned – was the Federalist Party. Spearheaded by former Treasury Secretary Alexander Hamilton, the Federalist movement had been born out of the controversy surrounding the making of the United States Constitution; that is, whether the national government should be strong and centralized with more authority over the states, as outlined in the Constitution, or whether it should be kept weak and loose, leaving the states with more autonomy, as had been the case under the old Articles of Confederation. Thanks to the efforts of men like Hamilton – who wrote the vast majority of the Federalist Papers arguing for ratification – the Constitution was ratified by the necessary nine states and went into effect in 1789.

Since then, the Federalist Party had become the nationalist party, concerned with expanding the power of the federal government even further. As treasury secretary, Hamilton had implemented a financial program whereby the national government assumed all state debts, helping to legitimize the national government in the eyes of creditors, as well as tying moneyed and influential men to the fortunes of the government. Hamilton had also implemented an excise tax on distilled spirits, which had led to an armed revolt known as the Whiskey Rebellion; the government's swift suppression of the rebellion ensured that its authority was felt even on the fringes of the country's western frontiers. Hamilton and the Federalists tended to hold views that could be considered aristocratic, believing that government should be run by well-educated men of status and influence, not by the common rabble. The Federalists were also characterized by their desire to form closer relations with Britain, which they viewed as the United States' natural ally, and by their aversion to the French Revolution (1789-1799), which they saw as the outcome of too much unregulated democracy.

By 1794, another political faction had risen to oppose the Federalists. The Democratic-Republican Party (also known as Republicans or Jeffersonian Democrats) believed in a small, limited national government, and thought that the states should largely be left to govern themselves. Led by Thomas Jefferson and James Madison, the Democratic-Republicans were disgusted by the Federalists' attitude toward the common man; they condemned the Federalists as 'aristocrats' and 'monarchists', and encouraged an expansion of republicanism. The Democratic-Republicans generally supported the French Revolution, even during the bloodletting of the Reign of Terror, and remained hostile toward Great Britain. The stark differences between the two parties' viewpoints often led to heated arguments, especially once partisan newspapers began popping up in major cities to spread the message of one party or another. By the time of the Farewell Address, the rift was only widening, with the upcoming presidential election promising to be the first major showdown between the parties.

The Candidates & Partisan Attacks

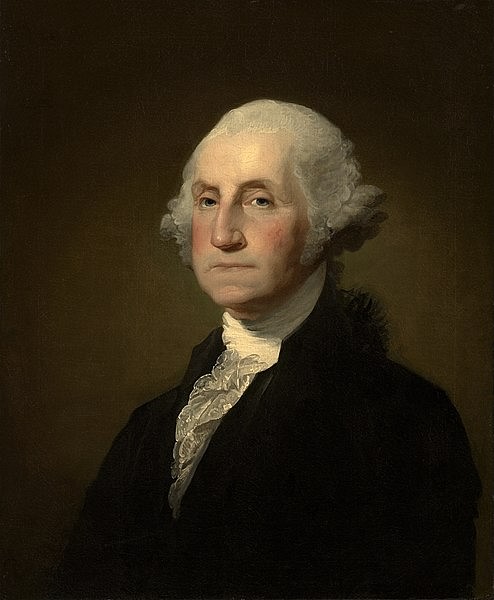

The publication of Washington's Farewell Address was, in the words of Massachusetts congressman Fisher Ames, "a signal, like the dropping of a hat, for the party racers to start" (Meacham, 299). For the first time, the outcome of a presidential election was uncertain, although each party already had its leading candidate. John Adams was the obvious choice for the Federalist ticket. As the incumbent vice president, he was considered by many Americans to be Washington's 'heir apparent'; indeed, Adams certainly viewed himself in such terms, as he privately remarked to friends that his 'succession' seemed likely (Wood, 210). For the Democratic-Republican ticket, no one seemed more qualified than Thomas Jefferson, the man who had informally led the Republican movement in its formative days during the Washington Administration.

Of course, neither man publicly announced that he was seeking the presidency, nor were they formally nominated by their respective parties. In those days, men who actively sought political office were treated with suspicion, meaning political hopefuls had to make their wishes known privately and sit on their hands as friends and allies campaigned on their behalf. Instead of campaigning, therefore, both Adams and Jefferson spent the months leading up to the election tending to their farms, Adams at his lifelong home in Quincy, Massachusetts (formerly Braintree), Jefferson on his beloved estate of Monticello. But while the candidates themselves were encouraged to stay aloof from the politicking, their partisan allies held nothing back.

On 29 September 1796, only ten days after the Farewell Address, an essay appeared in the Federalist newspaper The Columbian Mirror and Alexandria Gazette. Written by Charles Simm, a Federalist lawyer, the essay derided Jefferson for his actions as governor of Virginia during the American Revolutionary War, particularly the moment when he fled Monticello rather than risk capture by British cavalry in 1781. According to Simm, Jefferson had fled "at the moment of an invasion of the enemy, by which great confusion, loss, and distress accrued to the State in the destruction of their public records" (Meacham, 300). For this act of cowardice, Simm concluded that Jefferson was too weak to be president. Other Federalist papers accused Jefferson of being an unprincipled atheist and a radical Jacobin who supported the bloody excesses of the French Revolution.

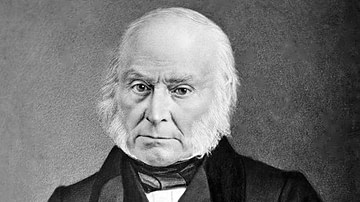

Those on the Jeffersonian side were no less cutthroat in their attacks. Benjamin Franklin Bache, the grandson of Benjamin Franklin and editor of the Democratic-Republican paper Philadelphia Aurora accused Adams of being a monarchist. Referring to Adams in mock-aristocratic fashion as 'His Rotundity', Bache told his readers that the vice president was the "champion of kings, ranks, and titles" (McCullough, 462). To protect republicanism, Bache argued, it was necessary to elect Jefferson, who was a true 'friend of the people'. Another paper, the Boston Gazette, accused Adams of scheming to make the presidential office hereditary to make way for his eldest son John Quincy. Thomas Paine, famed author of the revolutionary pamphlet Common Sense, unleashed the most scathing denouncement of Adams and the Washington Administration. Writing from Paris, Paine went so far as to attack Washington himself, referring to the president as a cold hypocrite incapable of friendship, as well as an apostate and imposter (ibid).

Hamilton's Schemes

While the partisan newspapers were duking it out, the political parties themselves were scrambling to secure support. With Jefferson publicly laying low, Democratic-Republicans rallied behind the leadership of his close ally, James Madison. One of their most pressing tasks was to choose a vice-presidential candidate; since Jefferson was from Virginia and was expected to carry the South, the Democratic-Republicans thought it prudent to select a running mate from the North. Various candidates were considered including Robert R. Livingston and George Clinton from New York as well as Samuel Adams from Massachusetts. In the end, a group of Democratic-Republican leaders decided to support Aaron Burr, a US senator from New York, as their vice-presidential candidate.

Leadership of the Federalist campaign fell to Alexander Hamilton. Although he was not currently holding a political office, Hamilton still enjoyed a great deal of influence within the Federalist Party; indeed, Noah Webster (of future dictionary fame) printed in his Federalist newspaper that Hamilton should be the one to succeed Washington, a notion that Hamilton himself was quick to disavow. The former treasury secretary knew that he was widely perceived as vain, arrogant, and aristocratic, and would have little chance at winning the presidency himself. Instead, he preferred to exert influence from the shadows, and sought to choose a presidential candidate who would adhere to his Federalist agenda. The fiery, egotistical Adams was too strong-willed for Hamilton's taste, leading him to consider Thomas Pinckney instead. Pinckney was a Revolutionary War veteran and former governor of South Carolina, who was riding high from his recent successful negotiation of the Treaty of San Lorenzo with Spain. Hamilton considered Pinckney to be a 'far more discreet and conciliatory' personality than Adams and thought that he would be better suited to advance the Federalist agenda.

So, Hamilton approached the Federalist electors and urged them to support Pinckney for vice president. According to the rules in effect at the time, members of the Electoral College could cast two votes, but they could not specify which candidate they wanted for president and which for vice president. If Hamilton could convince every Federalist elector to vote for both Adams and Pinckney, all it would take would be a handful of Democratic-Republican electors to cross party lines and vote for Pinckney as well for Pinckney to win more votes than Adams and 'accidentally' be elected president. At first, Adams did not suspect that Hamilton was scheming against him. It was only in December, when his friend Elbridge Gerry presented him with evidence, that he learned the truth. Whatever respect had remained between Hamilton and Adams before then was forever tarnished; John's wife, Abigail Adams, always thereafter referred to Hamilton as 'Cassius', while Adams himself called Hamilton "as great a hypocrite as any in the US. His intrigues in the election I despise" (Chernow, 511).

But it was not just Adams that Hamilton schemed against. His primary objective, of course, was to keep his rival Jefferson far away from the presidential office. Between October and November, a series of anti-Jeffersonian essays appeared in the Gazette of the United States, authored by someone using the pseudonym 'Phocion'. In the essays, Phocion mocked Jefferson's reputation as a moral philosopher, asking how someone who supported the 'cruelties' of the French Revolution could make a good president. He also brought up Jefferson's contradictory views on the issue of slavery, writing:

At one moment, [Jefferson] is anxious to emancipate the blacks to vindicate the liberty of the human race. At another, he discovers that the blacks are of a different race and therefore, when emancipated, they must be instantly removed beyond the reach of mixture lest he (or she) should stain the blood of his (or her) master, not recollecting what from his situation and other circumstances he ought to have recollected – that this mixture may take place while the negro remains in slavery. He must have seen all around him sufficient marks of this staining of blood to have been convinced that retaining them in slavery would not prevent it.

(Chernow, 513)

Phocion's mention of the emancipation of slaves was, of course, done to help turn the Southern slave-holding class against Jefferson. But, of more interest to a modern observer, is Phocion's references to the 'staining of blood' and 'mixture' that he accuses Jefferson of seeing all around him. This is heavily implied to be in reference to Sally Hemings, an enslaved woman whom Jefferson kept as a mistress and by whom he likely had several biracial children. Phocion's references to Hemings are interesting, as the scandal had not yet come to light. Of course, while it is not known for certain who authored the 'Phocion' essays, the author is widely believed to be Hamilton himself.

Outcome

Voting began on 4 November 1796 and lasted until early December. Since the last election, the states of Vermont, Kentucky, and Tennessee had entered the Union, increasing the number of electors to 138. Each elector was allotted two votes; whoever received the most votes would become president, while the runner-up became vice president, no matter the political affiliation. When the votes were tallied in February 1797, it was discovered that Adams had won the presidency, carrying 71 electoral votes. Jefferson received the second most votes at 68; this meant that, despite being from the opposite party as Adams, Jefferson was elected vice president. Pinckney emerged in third place with 59 votes, with Burr coming in fourth with 30. The states more or less voted along party lines; the Federalists won every Northern state except Pennsylvania, while the Democratic-Republicans won most of the Southern states except for Maryland and Delaware.

On 4 March 1797, Adams was inaugurated as the second president of the United States in Philadelphia, and Jefferson was sworn in as the second vice president. Many Americans took this as a good omen, that the two men, each the head of their respective party, would put aside their differences and work together, thereby ending the threat of factionalism. However, this was not to be. Over the next four years, Adams and the Federalist-controlled Congress would implement contentious policies, such as the expansion of the US Navy, the Quasi-War with France, and most controversially, the Alien and Sedition Acts of 1798. These policies only served to deepen the political divide in the country so that the US Presidential Election of 1800 – which ended up being a rematch between Adams and Jefferson – was even more bitterly partisan than in 1796.