Umar ibn al-Khattab (r. 634-644 CE) was the second caliph of the Rashidun Caliphate (632-661 CE, as the first four caliphs are referred to by the Sunni Muslims). He was an early convert of Islam and one of the close companions of the Islamic Prophet Muhammad (l. 570-632 CE). After the death of Muhammad, he gave his utmost and loyal support to Abu Bakr, who then became the first caliph. After Abu Bakr's death in 634 CE, Umar became the next caliph – he continued his predecessor's campaigns and extended his dominion further from the Arabian Peninsula. In addition to multiple military successes, his reign was marked with marvels in administration. After his death, he was succeeded by Uthman ibn Affan (l. 579-656 CE) as the third ruler of the Rashidun Caliphate.

Early Life & Conversion to Islam

Umar ibn al-Khattab was the son of Khattab ibn Nufayl; he was born in Mecca in 584 CE. Although well educated, he was fond of and skilled in fighting and horseback riding; he had earned quite a reputation as a wrestler. Like Paul the Apostle in Christianity, Umar was a persecutor-turned-believer; he initially despised Muhammad but then became a devout follower, and at times, he even defended the Muslims against physical harassment from the Meccans.

While most of Muhammad's companions slipped out from Mecca undetected during the hegira (migration to Medina in 622 CE), Umar is said to have openly declared his departure and challenged anyone to stop him from doing so – no one did. In Medina, he continued to extend his support for Muhammad and was one of his close confidants, he even participated in the battles of Badr and Uhud (624 and 625 CE respectively). His daughter Hafsa (l. 605-665 CE), who had been widowed in 624 CE, was married to the Prophet in 625 CE, hence making Umar his father-in-law, alongside Abu Bakr, cementing his relationship with the Prophet.

Caliphate

After Muhammad's death, Umar realized Abu Bakr's ability and gave him full support in his bid for the leadership of the community, helping him become the first Caliph of the Rashidun Caliphate; this position was also contested for by the partisans (Shia) of Ali ibn abi-Talib (l. 601-661 CE, another close companion and son-in-law of the Prophet). After Abu Bakr's success, Umar served as his counsel and learned a great deal from him as well (most importantly leadership). Caliph Abu Bakr (r. 632-634 CE) faced open rebellion of apostates (people who had forsaken Islam) all over the Arabian Peninsula. He subjugated all of them in what came to be known as the Ridda Wars or the wars of apostasy (632-633 CE). After reuniting the Arabs, Abu Bakr launched invasions into Byzantine-held Syria and Sassanian-held Iraq in 633 CE, which bore fruit by the time of his death in 634 CE (despite a minor setback in Iraq).

The most notable military figure of Abu Bakr's era was Khalid ibn al-Walid (l. 585-642 CE), Abu Bakr had cherished him (despite his flaws) for his unique talent in warfare. Khalid's skills proved to be much needed in the Ridda Wars and in the subsequent invasion of Iraq as well; from Iraq, he moved to the Syrian front to confront a major Byzantine counterattack, on the orders of Abu Bakr, at the Battle of Ajnadayn (634 CE). That day proved to be a decisive Muslim victory but Abu Bakr did not live long enough to enjoy the success and the Muslim advance in Iraq had also been compromised in Khalid's absence. At his death bed, Abu Bakr nominated Umar as his successor, who then became the Caliph in 634 CE (he added the phrase “commander of the faithful” after his title) and ruled for ten years until 644 CE. Umar's first priority was to consolidate his hold over the empire and get a grip on the administration, he then turned his attention towards the ongoing campaigns in Iraq and Syria.

Umar stripped Khalid of his command of the Syrian division for uncertain and highly debated reasons. He instead entrusted the command to his favorite person: Abu Ubaidah (l. 583-639 CE), a humane leader and a true gentleman; he had also been one of Muhammad's favorite companions (there were ten in total, four of whom were the four Rashidun Caliphs). The Caliph also reinforced the Muslim forces in Iraq with fresh troops under a new leader: Sa'd ibn Abi Waqqas (l. 595-674 CE).

Battles of Yarmouk & Al-Qadisiyya

In 636 CE, the Byzantine Empire struck back at the Muslims. Although Khalid was no longer officially in command, he was highly respected by the soldiers owing to his expertise in warfare and, taking his advice, the Muslim forces retreated to the Yarmouk River. It was here that the battle that would determine the fate of the region for centuries to come took place. The elite Byzantine troops outnumbered their foes, but Khalid was no stranger to fighting against odds. The Byzantines suffered a crushing defeat; the army was routed with slaughter and many perished due to drowning in the river. Not only did the Muslim position in Syria become uncontested but they also took hold of the Levant soon after; later in the same year, they were at the gates of Jerusalem – the third holiest Islamic city, also holy for the Jews and Christians.

The same year, on the other side of the Syrian Desert, the Saracen forces (as European history refers to Arabs and Muslims) under Sa'ad met the mighty Sassanian Empire under their legendary leader: Rustam Farrokhzad – a man with a similar reputation to that of Khalid. The Battle of al-Qadisiyya (636 CE) proved to be hopeless for the Arabs at first but the fateful death of Rustam demoralized his forces who were then utterly defeated. The Rashidun forces had emerged triumphant against staggering odds once again, and this victory had immediately brought the whole of Iraq and the Sassanian capital of Ctesiphon under their control. Umar ordered the forces to not to proceed into the unfamiliar territory of Iran, lest they be defeated and their gains reversed. The importance of these two victories cannot be overstated; the defenses of the opposing forces were crushed and they could not field effective counterattacks at similar levels anymore.

After the success at Yarmouk, Umar arrived in Syria and the Levant primarily to receive the surrender of Jerusalem (which was under siege) and also to manage domestic affairs in the region. Umar removed Khalid from command for good; sources argue whether Umar had personal problems with him or if it was due to Khalid's harsh nature. The vast majority of the Muslim historians suggest that Umar might have done so to show that it was God who gave them their victories and that no matter who led them, God's help was the only determining factor; at least this was what he announced in public. It is possible that Umar might have actually thought exactly as he had declared or his actual reason was one of the two mentioned above; the real reason remains shrouded in mystery.

Khalid, despite some controversies against him, was very popular among the Muslim troops who would follow him into any battle, no matter how bad the odds were. Before his dismissal, Khalid had led successful expeditions into Anatolia and Armenia in 638 CE, and though he was encouraged to rebel against the Caliph, he refused to do so and retired peacefully. Umar appointed Abu Ubaidah as the governor of Syria – he had also wished to nominate him as his successor, but the latter died in 639 CE in the wake of the plague that devastated the area.

Surrender of Jerusalem

Jerusalem is a holy city for Muslims, just as it is for Christians and Jews. According to Islamic tradition, Prophet Muhammad is said to have journeyed in 621 CE to the city overnight and ascended to heaven from there; the exact nature of this travel is debated by Muslims: some claim it to be a dream, others suggest that the journey was astral, and still others say that it was a physical journey. In either case, Jerusalem acquired unprecedented importance in Islam thereafter.

In 637 CE, when the Muslim forces were at the doors of the holy city, the Patriarch of Jerusalem: Sophronius (l. c. 560-638 CE), seeing that no Byzantine force was to come for their relief, sued for a peaceful surrender, personally to Umar. As noted earlier, this prompted the Caliph to depart his capital without any entourage and in a completely unceremonious manner; he reached Syria where he offered lenient terms to the newly conquered cities (as Khalid had done as well), and then he went to Jerusalem, where he was given a guided tour of the city by Sophronius, who then surrendered it to him. More than five centuries earlier, in 70 CE, the Romans had ousted the Jews from the holy city, Umar allowed them to return to it – as it was holy for them too.

Further Imperial Gains

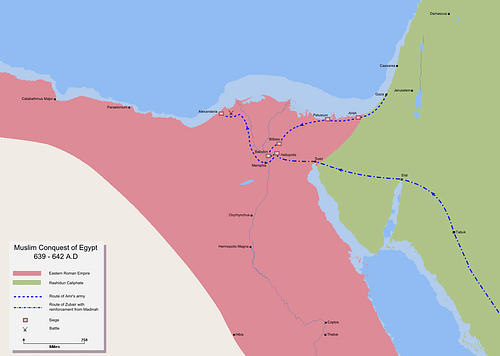

After strengthening his hold over Syria and the Levant, in 640 CE, Umar was convinced by Amr ibn al-Aas (l. c. 573-664 CE, one of the military commanders who had been sent to Syria in Abu Bakr's reign) to invade Egypt on the pretext of cutting off Byzantine naval assaults on the Levant. Umar, a man of cautious nature, was reluctant at first to risk such a grand undertaking but he eventually bent to Amr's will. Reinforced by the Caliph's forces under Zubayr ibn al-Awamm (l. 594-656 CE), Amr faced the Byzantine army, which was decisively defeated in the Battle of Heliopolis (640 CE), and by 642 CE, Egypt had been taken.

Administration

The military successes of Umar's reign tend to remain the focal point of most histories written about him, but his administrative skills easily overshadow the achievements on the field, some of the most important features of Umar's policy are as follows:

- Lenient terms were offered to newly conquered people, including religious freedom; although they were to pay a special tax called jizya.

- The purchase of land in newly acquired territories was prohibited.

- Troops were housed separately from local populations in garrison cities.

- Pensions, police force, courts, and allowances were introduced to facilitate people.

- A permanent state treasury called Bayt al Mal (house of fortune) was established.

- An uncompromising judicial system based upon supreme standards of justice was established.

To the people who had come under his rule through conquest, he offered lenient terms, low taxes, complete protection from abusive governors or troops and religious independence. Since non-Muslims were exempt from the payment of alms (zakat) or from military duty (which was obligatory on all able-bodied Muslims), they were subject to a separate tax – jiziya, and they were referred to as dhimi (protected people). Umar also kept tribal feuds of the hothead Arabs from surfacing through his strict rule – his successors would not be as successful as him in doing so.

Instead of distributing conquered lands among troops, as must have been expected from a desert sheikh, Umar introduced pensions for his men (to be paid by a bureaucratic office named the diwan) and allowed landowners to retain their properties. He also safeguarded the newly conquered people from molestation from rogue soldiers by building garrison cities to house the armies – separate from the locals: examples of such cities include Fustat in Egypt; and Kufa and Basra in Iraq.

He tackled several serious and dire issues such as the devastation brought about by the plague in Syria – after which Muawiya (l. 602-680 CE) was sent as the new governor as Abu Ubaidah had passed away. He also distributed food among the local population during a famine in Arabia (638 CE), saving the lives of countless people. Not only did he introduce judges and juries for handling local cases but he also introduced special courts for holding officials accountable for misuse of power. A police force was introduced to maintain discipline in cities, instead of handing over such a delicate duty to the armies. To finance such institutions and to provide for the people, a permanent state treasury: the Bayt al Mal (house of fortune) was established.

Umar's love for justice surpasses all of his other traits, both in determining the effectiveness of his rule and his posthumous fame (at least in the eyes of the Sunnis and even some Shias as well). Owing to his just nature, he had earned the title of Farooq, the one who distinguishes between right and wrong. In Islamic tradition, a story often associated with him dictates that he flogged his own son on charges of adultery and the poor lad died. The charges were proven false after his death, but the grieve-stricken father did not avenge his beloved son.

Although this incident (and many more like it) may not be more than just a fable, one can still see the impact of his character that might have inspired such odes in his favor, centuries after his death. Scholar Syed Ameer Ali also makes mention of one such incidence:

When the spoils of Jalula and Madain (from Iraq; Madain refers to Ctesiphon) arrived at Medina, the Caliph was found weeping. Asked his reason, he replied that he saw in those spoils the future ruin of his people, and he was not wrong… (29-30)

Death & Legacy

In 644 CE, whilst offering prayer in congregation, Umar was stabbed repeatedly on the back by a Persian slave named Lu'lu. Some say that the slave had some personal grudge against the Caliph, while other prominent historians (such as Saunders) claim that it was act of retribution for the Persian defeat in the Battle of Nihavand – the man was stricken with shame at the loss of his civilization and decided to avenge his brethren who had fallen in the field.

Umar was a practical person and realized that his wounds were fatal when he was taken to his home. Upon his inquiry about his assailant, he expressed relief in knowing that he had not been killed by a fellow Muslim. He then appointed a six-member committee, comprised of able men to elect a new caliph. Umar declared his honesty in the matter and stated that he had not selected his own son or any one of his kinsmen; after Umar's death, Uthman was chosen as Umar's successor. The old Caliph died leaving behind a lasting legacy, to be carried on for centuries after his death. In his book A History of Medieval Islam, historian John Joseph Saunders entitled him as the “real founder of the Arab empire”. He was buried near the Prophet's gravesite (part of the al-Masjid an-Nabwi in Medina).

In his successful reign of ten years, not only had Umar ruled effectively but he had also managed to take all of the Sassanian dominions and a major chunk of the former land of the Caesars. These military gains, which were a prelude of things to come, would continue to bring heaps of revenue to the empire – which would in time be used to finance grand projects, such as the Al-Aqsa mosque, whose foundations were laid down by Umar in Jerusalem (it would be further aggrandized by subsequent rulers).

Umar's administrative system would form the basic framework on which Islamic Caliphates would continue to be managed by his successors after his death. The Islamic calendar – one of the most important heritage of Muslims, was formulated by him; based on the Arabian lunar calendar, it holds the year of the hegira as year zero, i.e. 0 AH / Zero “After Hegira” (Prophet Muhammad's migration from Mecca to Medina in 622 CE).

Umar's personality and his legitimacy have been subject to controversy. While the Sunnis (who hold the claim of all four Rashidun Caliphs as equally legitimate) view him as a man of uncompromising standards of morality and justice, Shias, on the other hand, regard him as a cruel person. Moreover, while mainstream Sunnis see his claim of Caliphate as being legitimate, the vast majority of the Shias consider him a usurper (alongside Abu Bakr and Uthman). Though such debates continue to rage on among the Muslims even centuries after his death, and there seems to be no end to them in sight, no rational person can undermine his achievements.