Utah Beach was the westernmost of the five beaches attacked in the D-Day Normandy landings of 6 June 1944 and the one taken with the fewest casualties. Paratroopers were also dropped behind Utah, and despite being widely dispersed and suffering heavy casualties, they managed to secure this western flank of the invasion and liberate the first French town, Ste-Mère-Église.

Operation Overlord

The amphibious assault on the beaches of Normandy was the first stage of Operation Overlord, which sought to free Western Europe from occupation by Nazi Germany. The supreme commander of the Allied invasion force was General Dwight D. Eisenhower (1890-1969), who had been in charge of the Allied operations in the Mediterranean. The commander-in-chief of the Normandy land forces, 39 divisions in all, was the experienced General Bernard Montgomery (1887-1976). Commanding the air element was Air Chief Marshal Trafford Leigh Mallory (1892-1944), with the naval element commanded by Admiral Bertram Ramsay (1883-1945).

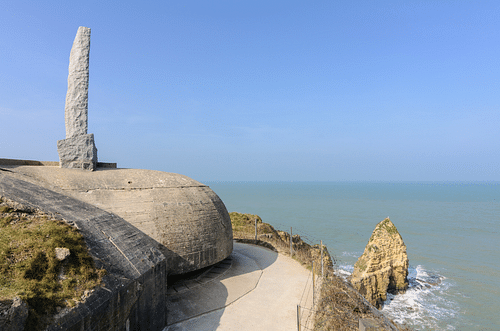

Nazi Germany had long prepared for an Allied invasion, but the German high command was unsure where exactly such an invasion would take place. Allied diversionary strategies added to the uncertainty, but the most likely places remained either the Pas de Calais, the closest point to British shores, or Normandy with its wide flat beaches. The Nazi leader Adolf Hitler (1889-1945) attempted to fortify the entire coast from Spain to the Netherlands with a series of bunkers, pillboxes, artillery batteries, and troops, but this Atlantic Wall, as he called it, was far from being complete in the summer of 1944. In addition, the wall was thin since there was no real depth to the defences.

Field Marshal Gerd von Rundstedt (1875-1953), commander-in-chief of the German army in the West, believed it would be impossible to stop an invasion on the coast and so it would be better to hold the bulk of the defensive forces as a mobile reserve to counterattack against enemy beachheads. Field Marshal Erwin Rommel (1891-1944), commander of Army Group B, disagreed and considered it essential to halt any invasion on the beaches themselves. Further, Rommel believed that Allied air superiority meant that movements of reserves would be severely hampered. Hitler agreed with Rommel, and so the defenders were strung out wherever the fortifications were at their weakest. Rommel improved the static defences and added steel anti-tank structures to all the larger beaches. In the end, Rundstedt was given a mobile reserve, but the compromise weakened both plans of defence.

The German response would not be helped either by their confused command structure, which meant that Rundstedt could not call on any armour (but Rommel, who reported directly to Hitler, could), and neither commander had any control over the paltry naval and air forces available or the separately controlled coastal batteries. Nevertheless, the defences were bulked up around the weaker defences of Normandy to an impressive 31 infantry divisions plus 10 armoured divisions and 7 reserve infantry divisions. The German army had another 13 divisions in other areas of France. A standard German division had a full strength of 15,000 men.

The Pre-D-Day Attacks

Preparation for Overlord occurred right through April and May of 1944 when the Royal Air Force (RAF) and the United States Air Force (USAAF) relentlessly bombed communications and transportation systems in France as well as coastal defences, airfields, industrial targets, and military installations. In total, over 200,000 missions were conducted to weaken as much as possible the Nazi defences ready for the infantry troops about to be involved in the largest troop movement in history. The French Resistance also played their part in preparing the way by blowing up train lines and communication systems that would ensure the German armed forces could not effectively respond to the invasion.

The Airborne Attack

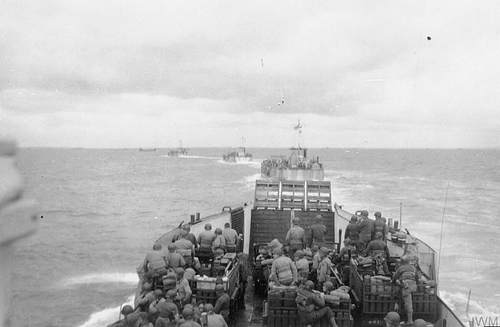

The Allied fleet of 7,000 vessels of all kinds departed from English south-coast ports such as Falmouth, Plymouth, Poole, Portsmouth, Newhaven, and Harwich. In an operation code-named Neptune, the ships gathered off Portsmouth in a zone called 'Piccadilly Circus' after the busy London road junction, and then made their way to Normandy and the assault areas. At the same time, gliders and planes flew to the Cherbourg peninsula in the west and Ouistreham on the eastern edge of the planned landing. Paratroopers of the 82nd and 101st US Airborne Divisions attacked in the west to secure the beach exits and vital bridges in the area (which would impede any German counterattack on the beaches), while also trying to cut off Cherbourg from the rest of the defensive force. At the eastern extremity of the operation, paratroopers of the 6th British Airborne Division aimed to secure the bridges and eastern flank of the invasion.

The airborne troops were dropped in the early hours of 6 June. The first drop was of pathfinders, who were supposed to set up beacons to guide subsequent troops, but only one of 18 pathfinder groups landed where they were supposed to land. The darkness, cloud cover, and German anti-aircraft guns combined to shift most of the planes off course, as they would do for those that followed.

The 13,000-plus paratroopers dropped behind Utah Beach became hopelessly dispersed. Only 4% of the US 101st Air Division were dropped at their intended target zone, and, three days later, 4,000 men of the 82nd were still missing. Many men dropped in the marshlands behind the beaches, an area full of canals and ditches, which had helped the German army to deliberately flood the low-lying fields precisely as a precaution against a paratroop attack. A significant number of the US troops, weighed down by equipment, drowned in the darkness in just over 3 feet (1 m) of water. Much of the heavier equipment like anti-tank guns was lost in this way, too. Other paratroops who avoided the flooded areas found themselves landing in fields of sharpened stakes, what the Germans called Rommelspargel or 'Rommel's asparagus'. These devices also caused havoc with the gliders landing later in the day.

For some US units, it would take days for personnel to find each other, meanwhile, many paratroopers simply fought where they were or joined infantry units. So bad was the result of the night drop that Allied commanders vowed never to conduct such an operation at night ever again. If anything, though, the wide dispersal of the paratroops caused even greater confusion amongst the German commanders on the ground, as it seemed to them that the Allies were attacking everywhere. Individuals and small groups of US troops caused havoc as best they could wherever they were, for example, cutting telegraph wires, which blacked out German communications.

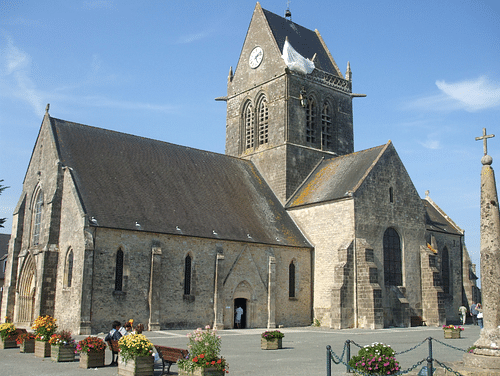

US paratroopers who dropped near Ste-Mère-Église behind Utah Beach ensured this was the first French town to be liberated. The town was important because it sat at the crossroads of the routes the German army could have used to reinforce Utah Beach or launch a counterattack from the northeast. Ste-Mère-Église came at a cost since some of the paratroop units had dropped directly over the town and were shot as they fell by German troops on the ground and a machine gun in the bell tower of the main church. Elsewhere, paratroopers of the 101st ensured the Utah Beach exits were protected by the time they were needed by their compatriots on the beach.

Another key mission was to capture the formidable gun emplacement above the cliffs of Pointe du Hoc, located between Utah and Omaha Beach and capable of firing on both areas. It was a target given to the US 2 and 5 Ranger Battalions. As it turned out, this series of encasements had had their guns removed, but the Rangers subsequently found them in the nearby forest, ready with ammunition and aimed at Utah. The guns were destroyed.

Later on the morning of D-Day, two waves of gliders landed with yet more troops and heavier equipment to reinforce the lightly armed units that had dropped in the night. Many gliders crash-landed as the landing areas proved to have larger hedges and trees than reconnaissance had suggested; many hit defensive obstacles, too. The airborne assault had gone completely wrong in terms of the original plan, but the difficulties were overcome, and the rear of Utah Beach was mostly secure. Now it was the turn of the infantry coming in from the sea.

The Amphibious Attack

The amphibious attack was set for dawn on 5 June, daylight being a requirement for the necessary air and naval support. Bad weather led to a postponement of 24 hours. From 3:00 a.m., air and naval bombardment of the Normandy coast began, letting up just 15 minutes before the first infantry troops landed on the beaches at 6:30 a.m. The area was divided into five beaches, each with its own code name. While US troops attacked Utah Beach and Omaha Beach to the west, Canadian troops landed at Juno Beach, and British troops launched an assault on Gold Beach and, at the eastern end of the front, on Sword Beach.

Utah Beach was 9 miles (14.5 km) long. The first landing craft hit the shore carrying a total of 32 amphibious tanks; 28 made it onto the beach. Follow-up waves came every five or ten minutes with infantry, more tanks, and specialised equipment like bulldozers to help clear the beach of obstacles. But all was not what it seemed. The neat plan of the landing was wrecked right at the start after three of the four craft designated to coordinate the attack were sunk by mines. Due to strong currents, the first wave had landed a mile further south than intended, but this meant most of the remaining defences were avoided. The German troops that were manning the defences at Utah were astonished and demoralised at the sight of amphibious tanks landing on the beach. Lieutenant Jahnke remembered:

Here was a truly lunatic sight. I wondered if I were hallucinating as a result of the bombardment. Amphibious tanks! This must be the Allies' secret weapon…It looks as though God and the world have forsaken us. What's happened to our airmen?

(Ambrose, 277)

The danger at Utah was in the water as the German heavy batteries hit far out to sea. Lieutenant Halsey Barrett, after his own patrol craft was sunk, describes his view of the first wave of landing craft:

A landing craft LCVP with thirty men aboard was blown a hundred feet in the air in pieces. Shore batteries flashed, splashes appeared sporadically around the bay.…Aft of us an LCT lay belly skyward no trace of survivors around it. The USS battleship Nevada a mile off to the northwest of us was using her 14-inch guns rapidly and with huge gushes of black smoke and flame extending yards and yards from her broadside…There was a beautiful sunrise…A small British ML picked up with difficulty one of our men shrieking for help while hanging on a marker buoy. His childish yells for help despite his life jacket and secure buoy was the only disgraceful and unmanly incident which I saw…

(Hastings, 88)

Also in that first wave was Brigadier-General Theodore Roosevelt Jr, the son of the former President Roosevelt. The conundrum of whether to move the troops back to their original planned landing point or carry on from where they were was solved when the general famously stated, "We'll start the war from right here" (Cawthorne, 195). The regiment commander Colonel James Van Fleet agreed, and so the attack pushed on.

Shallow-bottomed landing craft, often crewed by British naval personnel, continued to disgorge troops on the beach, the men having to survive mines and enemy machine gun, artillery, and sniper fire, but all less intense than at the other beaches. Here, the naval and air bombardment successfully knocked out most of the bunkers and pillboxes. Smoke bombs were fired to obscure the beach, and the men waded through the last 300 yards (275 m) to reach the shore. Several German gun posts surrendered without too much of a fight, but others did resist and continued to fire repeatedly upon the beach, notably the strongpoint at St Marie du Mont. A naval bombardment helped put St Marie du Mont out of action; the excellent communication and response between land and naval forces was a particular feature of the landing at Utah Beach.

By just after noon, the beach had been cleared, and only six men had been killed. This was in stark contrast to the heavy casualties being endured by the US troops on Omaha Beach just 13 miles (21 km) down the coast. More and more waves of men landed on Utah as the first troops began to move inland. German artillery guns inland were still firing upon the beach, although without any great accuracy since they now had no information coming in from observation posts on the beach itself. The area behind Utah Beach was heavily mined, and this accounted for many of the Allied casualties here.

Tom Treanor, a war correspondent, gives the following account of his landing that day:

We came sliding and slewing in on some light breakers and grounded. I stepped ashore on France, walking up a beach where men were moving casually about carrying equipment inshore. Up the coast, a few hundred yards, German shells were pounding in regularly, but in our area it was peacefully busy. 'How did you make out?' I asked one of the men. 'It was reasonably soft,' he said. 'The Germans had some machine-gun posts and some high-velocity guns on the palisades and made it a little hot at first. They waited until the landing craft dropped their ramps, then opened up on them while the men were still inside. Then the navy went to work on the German guns and it wasn't long before they were quiet.

The engineers and beach battalions had blown gaps in the barbed wire through which we could move vehicles. A few dead lay about and some wounded men were here and there on stretchers awaiting transport to ships out at sea…I began to step past men, following a captain. Suddenly a voice said, 'Watch yourself, fella. That's a mine.' A soldier sprawled on the bank was speaking. He had one foot half blown off. He'd stepped on a mine a short time earlier. Now, while he waited for litter-bearers, he was warning other soldiers about other mines in the vicinity.

I took a last look at the greatest armada in history. It was too immense to describe. There were so many transports on the horizon that in the faint haze they looked like a shoreline.

(Bailey, 289-91)

On D-Day, 23,250 troops were landed at Utah, with the loss of around 200 men (although no official figures for D-Day alone exist, and estimates vary. Some historians prefer a figure of 300 casualties for Utah). By the end of the day, the troops from Utah Beach had linked up with several units of the 101st and 82nd Airborne Divisions.

The Battle for Normandy

At D-Day's end, 135,000 men had been landed in Normandy, and relatively few casualties were sustained – some 5,000 men. The defenders eventually organised themselves into a counterattack, deploying their reserves and pulling in troops from other parts of France. This is when French resistance and Allied aerial bombing became crucial, seriously hampering the German commanders' efforts to reinforce the coastal areas of Normandy. Most of the German generals wanted to withdraw, regroup, and then reattack in force, but, on 11 June, Hitler ordered there be no retreat.

Cherbourg was taken on 27 June and was used to ship in more troops and supplies, although the defenders had sunk ships to block the harbour, and these took some six weeks to fully clear. Operation Neptune officially ended on 30 June. Around 850,000 men, 148,800 vehicles, and 570,000 tons of stores and equipment had been landed since D-Day. The next phase of Overlord was to push the German army out of Normandy, but this proved more difficult than anticipated, with the defenders fighting resolutely and aided by the broken bocage countryside of fields and hedgerows. There were some serious Allied setbacks such as the staunch defence of Caen and very heavy fighting around Avranches. It was not until August that General Patton and the US Third Army were punching south at the western side of the offensive. The Brittany ports of St. Malo, Brest, and Lorient were taken, and the Allies swept southwards to the Loire River from St Nazaire to Orléans. On 15 August, a major landing took place on the southern coast of France, the French Riviera landings. On 25 August, Paris was liberated. The northern and southern Allied armies linked up in September and pushed the German army back towards Germany as the Second World War reached its final phase.