Saint Valentine’s Day, or simply Valentine’s Day, is celebrated on the 14th of February, almost internationally but primarily in western societies. It is a commemorative Christian feast for some but a secular occasion for others who see it as a day to celebrate affection in all of its forms but primarily romantic love. The day has been named after one or more martyrs of the early Christian era named Valentine or Valentinus who lived sometime in the 3rd century CE and was killed for defying oppressive laws directed either against Christians or young lovers in the Roman Empire. Valentine’s death became symbolic during and after the Christianization of the Roman Empire, and later on, the character developed a correlation with romantic love throughout Europe, and then the idea spread almost internationally.

Historical Background

According to Christian chronicles and legends, most of which are impossible to attest historically, Valentine’s legendary sacrifice took place sometime in the 3rd century CE. The pagan Roman Empire had been pushing hard against a new group of believers, who had been moved by the message of a man named Jesus of Nazareth, also known as Jesus Christ (l. c. 4 BCE - 33 CE). The Romans were not all too thrilled by the spread of Christianity for various reasons and used all the means, even the most violent and oppressive ones, at their disposal to deter conversions but these efforts proved to be ultimately futile.

However, the Romans had something much more serious to worry about at the time. With the murder of Roman emperor Severus Alexander (r. 222-235 CE), the empire was plunged into the Crisis of the Third Century (235-284 CE). Alexander's 13-year long reign saw him effectively contain the pressure of the Sassanian Persian Empire (224-651 CE) in the east, but his attempts at seeking a diplomatic solution with the unruly Germanic tribes in the north alienated his own army who then resorted to betray and kill him. However, the emperor’s death caused more problems than anticipated: the unified Roman Empire cracked and fractured under the pressure of invasions, revolts, and political instability.

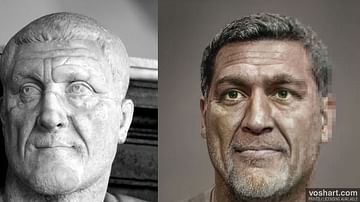

Thus under such tumult and chaos, the main antagonist of the Christian accounts of Valentine, Claudius Gothicus, also known as Claudius II (r. 268-270 CE), rose to the status of the Roman imperator. Like most barracks emperors, his brief reign was dotted with military action. His victory against the Goths in 268/269 CE at the Battle of Naissus proved to be a turning point that would allow Emperor Aurelian (r. 270-275 CE) to reunite the realm under his rule. Though a hero in the annals of imperial Roman history, Claudius II is viewed as an oppressive tyrant in the Christian chronicles detailing his confrontation (if there was any) with Valentine.

History of Saint Valentine

At least three individuals by the name of Valentinus (Valentine) in or around the aforementioned period, in Rome or Terni (and in Africa as well), have been associated with the holiday, and all of them were martyred by the Romans. The first variant of the legend dictates the story of a Christian priest in Rome, named Valentine, who defied orders from Claudius II which restricted young men from marrying as he was in dire need of troops to fight rival powers. This created an unsurpassable legal barrier for young lovers who wished nothing but to be together. At this point, Valentine stepped in and wed young couples in secret.

Another version narrates that he helped persecuted Christians escape their tormentors. In both of these versions (and many more like these), Valentine was arrested and presumably brought before Claudius II, which is unlikely to have happened since he was endlessly engaged in warfare and often absent from the capital, bringing doubt to the legend. Nevertheless, Valentine and Claudius supposedly exchanged a few words, and the emperor offered to spare Valentine if he renounced Jesus Christ, which he did not. Following this, the priest was beaten and then beheaded.

Another version narrates that he was thrown into prison, where he lived out his last days and was visited by grateful couples who would bring him flowers. He then fell for his jailor’s daughter, who, in one variant of the story, was blind and Valentine cured her, which moved his jailor and his household to accept Christianity – this, as with all the other aspects of the legend, cannot be verified. Before meeting his end, Valentine is said to have written the first valentine card for the jailor's daughter, signed: "From your Valentine."

Accounts of Valentine come only centuries after his death. The persecution of Christians in the Roman Empire is well attested and we have reason to believe that Valentine, or at least someone with a similar persona, may have been executed for not renouncing his faith or aiding fellow Christians. The gaps left in the story could have only been filled by contemporary records, none of which survives as they were presumably destroyed under the reign of Emperor Diocletian (r. 284-305 CE) who was strictly anti-Christian. Centuries later, writers and chroniclers added to the story, as they saw fit, to mold it perfectly for use as an inspiration for Valentine’s Day.

There is no way of knowing for sure if Valentine was killed on 14 February, or if he could miraculously cure diseases, or if he wore a ring with the engraving of Cupid – a pagan symbol – or if there were one or more Valentines, or if Valentine existed at all. What we do know is that he was officially declared a saint by the end of the 5th century CE. The same Roman Empire that had tightened the noose against its Christian citizens was to see Christianity rise as the biggest faith in the empire following the conversion of Emperor Constantine I, also known as Constantine the Great (r. 306-337 CE) in 312 CE.

Origins of the Saint Valentine’s Day

How Valentine’s Day became a thing, and that too in February – a month arbitrarily linked with courtship and romance, is a completely different story. February had been very important for the Romans; Just as the mid of the month approached, the air echoed with cheers of joy as people made ready to celebrate the pagan festival of Lupercalia, dedicated to Faunus, the Roman god of agriculture, and to Romulus and Remus, the mythological founders of Rome. The name presumably derives its etymology from lupus, meaning wolf and perhaps referring to the she-wolf, which, according to one form of the legend of Romulus, raised the two boys who founded the city.

The festival involved the sacrifice of a goat and a dog; the goat’s hide would be cut into strips and dipped in its blood, and priests, called Luperci, would then carry these strips and gently slap crop fields and women with them, with the latter being eager for this treatment as they believed that it would make them more fertile in the coming year. Young women would then proceed to put their names in a large urn from which bachelors would take one and be bonded to that woman for the whole year. They could participate in all forms of physical relationship, and most but not all of these relationships would end in marriage.

Naturally, when the Roman Empire was Christianized, such pagan activities were deemed unacceptable. Many pagan celebrations were replaced with Christian holidays, and thus Lupercalia (if it was indeed practiced this way and in February) may have also transformed into something more acceptable to the church.

We do know that moving the birthday of Jesus Christ, formally known as Christmas, to December was intentional even though there is no archaeological or historical evidence to suggest that Jesus was born in December, and was done simply to replace the pagan celebrations of late December in honor of their sun god: Sol Invictus, who, according to Roman mythology, would regain his strength from that point on as days started to become longer. Thus, presuming that Valentine's Day was shaped for erasing pagan influences in the Roman culture and replacing it with something Christian, without changing much about the culture itself, does not seem farfetched.

Association With Romantic Love In Europe & Beyond

We are left clueless about the original purpose that Saint Valentine’s Day served. Whether it simply toned down the elements of Lupercalia or it was a commemorative day for the martyrs of the early Christian era, we have no way of knowing. However, it did get associated with romantic love in Europe. Courtly love, though a modern term coined in the 19th century CE, was not unseen in Europe even in Roman times.

People did not always relate love with marriage in pre-Christian Roman society. Although having both together was deemed lucky, we come across tales of several romantic partners torn apart by social barriers. We know of these stories through Roman literature such as poems by Catullus (84-54 BCE) which reflect his desperate hopes to be united with his lover, who was unhappily married to another man; a wishful thought that would never materialize. In later history, we come across stories like William Shakespeare’s (l. 1564-1616 CE) masterpiece Romeo and Juliet (1597 CE), a work of fiction placed, once again, in Italy, showing two lovers joined at heart but separated by social preconceptions.

Thus our understanding of romantic love in modern society, which is often related to marriage, differs from the way it was seen in classical and medieval times. If Valentine's Day was indeed celebrated to commemorate love, then it may have replaced Lupercalia. However, if the day was meant to commemorate the martyrdom of saints who refused to bow before pressure and renounce their faith in Jesus Christ, then this association may have been developed over time through minor changes in the narrative of Valentine's story.

In his c. 700 lines poem, Parliament of Fowls (originally Parlement of Foules), published in 1382 CE, Geoffrey Chaucer (l. c. 1340-1400 CE), who is regarded as one of the greatest English poets and writers of medieval literature, notes:

For this was on Saint Valentine’s day,

When every fowl comes there his mate to take,

Of every species that men know, I say,

And then so huge a crowd did they make,

(Parliament of Fowls – Translated by A. S. Kline, 2007)

This association of Valentine’s day with courtly love is the first we come across in history. Observers are left in the dark as to whether Chaucer wrote these verses (and others like it) after being inspired by the way this day was celebrated in his times, or if he just added the reference as a work of fiction which then inspired the day to become associated with love. Similarly, the association of February with affection and love may have been a result of Chaucer's rendition in Parliament of Fowls, rather than the other way around.

Valentine’s day could have been officiated by the Church as early as the late 5th century CE or may have surfaced in medieval times following works like Chaucer's. We do know that the day draws on heavily from pre-Christian Roman culture, for instance, the month, the theme, the target audience, and even the Cupid. According to one version of Valentine's story, in which he wed young couples, the saint wore a ring bearing an amethyst stone and an engraving of this Roman deity – lovers would recognize him through this symbol and beseech his help.

The only complication here is the fact that the Cupid was a non-Christian symbol at the time. Deemed as the child of Roman gods Mars (god of war) and Venus (the love goddess), Cupid has been artistically depicted as a winged chubby child bearing his famous bow and arrow. In classical mythology, anyone shot by his arrow will lose themselves to love. In some depictions, Cupid is shown as a menacing character, often plotting nefarious schemes such as shooting people with his arrows even though there was no chance of them getting together thus forcing them to ruin their lives in a fruitless pursuit. His mother, Venus would often reprimand him for his behavior, as is evident in several graphic art forms that depict the two together.

In one story, titled Cupid and Psyche, the only tale which features the naughty god of attraction as a main character, Cupid falls for the same unsurmountable desire which he had supplanted in so many hearts when he is wounded by his arrow and embraces the love of Psyche, a maiden "so radiantly fair that no suitor seemed worthy of her" (Peabody, 89).

As the Christianization of the Roman Empire progressed, the references of pagan gods were erased with only nominal remains left such as the months or planets named in their honor, however, the iconography of the Cupid seems to have survived, or maybe revived, during the Renaissance. By this time, his nasty habits were toned down and he became a symbol of love in both the earth and the heavens. Since the Cupid shares this one element with Valentine's Day and nothing else, it was gradually amalgamated into the mix and became an icon associated with the day of love, perhaps even more prominent than the man whose sacrifice set it all in motion.

Valentine’s Day In The Present

Though its origins remain shrouded in mystery and may never unveil themselves, and despite its mix of pagan and Christian symbolism – Valentine's day is celebrated almost internationally, although in different manners. For some, it is a Christian holiday – a feast that commemorates Saint Valentine’s sacrifice, while others look at it through a more secular lens – which is understandable considering the mixture of iconographies and messages associated with the day, many of which are not parallel with Christian values (such as premarital or extramarital intimacy).

Before 14 February, almost internationally, a host of holiday-themed gifts, cards, roses, and heart-shaped balloons fill the display cases of shops and sidewalk vendor stalls alike. Valentine’s Day has in the past century risen from the shadows of anonymity, hidden in the annals of European history, and gripped the international audience, mostly propagated through the influx of European culture in various parts of the world, and through other channels of cultural diffusion, most prominently the electronic and digital media.

A 2012 CE article in the Guardian, ranks Saint Valentine's Day as the second biggest card-selling holiday (Christmas being the first), globally, with over 151 million cards bought globally. However, many are opposed to the celebration of this day, especially in the Muslim world and several other countries which either see it as an encroachment of 'foreign culture' in their society or as a painful reminder of their colonial past. The holiday is not necessarily Christian in modern times, but its origins are indeed deeply embedded in the past of Christianity. We may or may not support the commemoration of love for a single day, but if Valentine was a real character, then the story of his sacrifice, having survived all these centuries, at least deserves a mention.