Vinland (Old Norse Vínland, 'Wine Land') is the name given to the lands explored and briefly settled by Norse Vikings in North America around 1000 CE, particularly referring to Newfoundland, where a Viking site known as L'Anse aux Meadows was uncovered in the 1960s CE, and the Gulf of St Lawrence. The term Vinland is sometimes used to indicate all areas frequented by the Vikings in North America, in which case it also stretches to Labrador, Baffin Island, New Brunswick, and Prince Edward Island, all in present-day Canada.

Vinland was hailed by the Norse as a land of riches, allegedly first set foot on by Leif Erikson, son of Erik the Red who founded the first Norse settlement of Greenland, and it became the objective of various expeditions seeking to bring its produce, timber, and furs back to Greenland and Iceland. The area was not uninhabited, however; contact with natives, besides being the first known instance of a meeting of people from Europe and America, was seemingly not always smooth, and together with the distance (some 3200 km) between Vinland and Greenland this probably led the Norse to conclude that these riches were not worth the extreme hassle. The Norse settlement at L'Anse aux Meadows on the northern tip of Newfoundland, which likely functioned as a sort of gateway from which trips were undertaken to other areas, seems to have been in use for only about a decade before it was purposefully abandoned. Occasional visits to the Labrador region in order to gather wood seem to have continued, though.

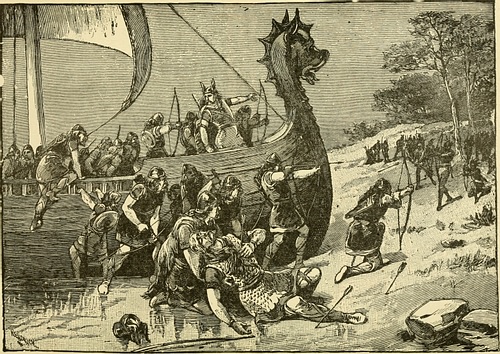

The Viking Discovery of America

In the 13th century CE, two Icelandic sagas, The Saga of the Greenlanders (Grœnlendinga saga) and Erik the Red's Saga (Eiríks saga rauða), were written down. They tell the stories of the Viking journeys to America, which allegedly took place sometime between c. 970-1030 CE, and are collectively known as the Vinland Sagas, although they were composed independently. While the two disagree on some points, their similarities are striking enough to support the idea that these sagas - although hardly eye-witness accounts - remember real people and events at least partially preserved through an oral tradition.

The Saga of the Greenlanders starts off with the story of Bjarni Herjólfsson, who, sailing towards his father in Greenland, is blown off-course to an unknown land that had "small hills, and was covered with forests" (Smiley, 637). As Bjarni decided not to go ashore, the credit for the first European to actually set foot on North American soil goes to Leif Erikson a few years after Bjarni's sighting. First, Leif and his crew reach a glacier-covered stone slab of land they name Helluland ('Stone-slab Land'), then a flat and forested land they call Markland ('Forest Land'), and eventually come upon a lush land where they found a base they name Leifsbúðir ('Leif's Booths'). While exploring the surrounding lands, Leif and his men discover grapes and timber which they bring back to the less plentiful Greenland, but not before naming the new area Vinland. His brothers Thorvald, Thorstein, sister Freydis, and his sister-in-law Gudrid with her husband, Thorfinn Karlsefni, all launch subsequent expeditions to America, exploring it further and coming into contact with the natives in both a positive and a negative way.

In Erik the Red's Saga, it is actually Leif Erikson who is blown off-course to North America, chancing upon a land with self-sown wheat, grapes, and maple trees, as well as rescuing some shipwrecked men and earning himself the nickname 'the Lucky'. This saga combines the four expeditions of The Saga of the Greenlanders into a single big one, led by Thorfinn Karlsefni and his wife Gudrid with a mainly Greenlandic-Norse crew. The main base in northern Vinland is here named Straumfjǫrðr ('Fjord of Currents'). It has been suggested that Karlsefni and Gudrid's role has been magnified in this saga at the expense of Leif's, who is all but erased, in connection with a movement in the 13th century CE which sought to canonise Bishop Björn Gilsson, a direct descendant of theirs.

Whether it was Bjarni's, Leif's, or someone else's ship, it is easy to imagine – and indeed a likely scenario – that the discovery of America by the Norse was a result of ships going off-course on the long stretch of open water between other Viking territories and Greenland, pushed by strong winds to unforeseen locations. Subsequently, an expedition would indeed have been launched from Greenland. Leif Erikson is actually a decent candidate for its historical leader, as the remains of the Viking settlement found at L'Anse aux Meadows in northern Newfoundland indicate the presence of an important chieftain. Leif, whose father Erik the Red ruled Norse Greenland at the time, would have been just that.

The Viking Presence in America

Tracking down the actual historical presence of the Norse in North America is not a simple matter of following the sagas as if they were a travel guide, directly translating its locations into colourful dots on detailed maps. Much discussion has gone into puzzling out which areas the Vikings may have touched upon in the decades surrounding 1000 CE, where possible uniting the scarce archaeological evidence with theories leaning on the saga descriptions.

The site of L'Anse aux Meadows provides the most tangible evidence, and it is likely that this unusually large settlement was used as a gateway where work crews could land, repair their ships, and overwinter to then launch expeditions to other more remote areas in the summer. Butternuts and butternut burls that were found at the site are not local but grow in the verdant area further south around the Gulf of St Lawrence including New Brunswick, indicating Norse journeys there. Grapes also grow there, which feature prominently in the Vinland Sagas and the name Vínland – Wine Land. Thus, it is generally thought that the Vinland from the sagas encompassed the whole area from the Strait of Belle Isle in Newfoundland to the Gulf of St Lawrence and its southern shores, perhaps stretching to Prince Edward Island and New Brunswick. North-eastern New Brunswick, possibly Chaleur Bay and Miramichi, might correspond with the lush and bountiful saga-area of Hóp.

Similarly, to the north of L'Anse aux Meadows, the wooded Markland from the sagas is thought to correspond with the central forest belt of Labrador. Thorvald, Leif's brother, supposedly met his death there, after being pierced with an arrow shot by natives. Helluland, named for stone slabs or flat rocks, seems to match northern Labrador and/or Baffin Island, while Kjalarnes or 'Keel Point', named for the keel of Thorvald's ship which smashed while being driven ashore there, might be one of the peninsulas near Sandwich Bay.

All of the area's resources, from good hunting and fishing to grapes, furs, iron, and plenty of timber, and the exploration of these lands together made up the chief goal of the Vinland voyages. The goods were probably gathered, stockpiled at L'Anse aux Meadows, and then ferried back home. That Vinland was a worthwhile endeavour is highlighted in the sagas, too: when The Saga of the Greenlanders discusses Karlsefni's successful trip back from Vinland to Greenland, it proclaims, "it is said that no richer ship has sailed from Greenland than the one he steered" (quoted in Sawyer, 117). It is thought that each expedition may have lasted between one and three years.

However, the Norse would not exactly have undertaken day trips to Hóp or to Helluland or have effortlessly commuted from Greenland to L'Anse aux Meadows. To give an indication of the vast distances involved: these last two are already more than 3000 km apart, and the journey would have taken an estimated minimum of two weeks (and perhaps as much as six weeks or more) in one direction. To continue on to New Brunswick or Labrador to gather the produce they were after easily adds another 1000 km to the journey (to not even speak of the remote Baffin Island, although this would have been easier to reach directly from Greenland, without stopping in L'Anse aux Meadows). These distances add up to significantly more than the 'only' c. 2500 km of sea route between Norse Greenland and Bergen in Norway. Although Viking ships were famously advanced, the journey would have been no cruise.

L'Anse aux Meadows

Because of the striking stories from the Vinland Sagas, interest in finding tangible archaeological evidence to support them goes back a long time. Already in the early 20th century CE fingers were pointed at northern Newfoundland as a good candidate for Leifsbúðir/Straumfjǫrðr, and in 1961 CE Norwegian writer and explorer Helge Ingstad uncovered what he thought were the remains of Norse buildings, at the site of L'Anse aux Meadows. Showered in scepticism, his wife Anne Stine Ingstad led excavations there between 1961-1968 CE which proved the Ingstads' claim was a substantial one. From 1973-1976 CE further excavations were undertaken there, led by Parks Canada.

The site of L'Anse aux Meadows is located on the western side of the northernmost tip of Newfoundland's Northern Peninsula, in a wide grassy cove close to the waters of the Strait of Belle Isle and facing the distant outline of Labrador's coast. The ruins lie on a narrow terrace about 100 m inland, sandwiched between bogs. Eight turf-walled buildings are present, seven of which are grouped into three complexes, with the eighth – a small hut – located away from the rest and nearer the shore. Each complex contains an imposing hall with multiple rooms alongside a small, single-roomed hut, and one of the complexes has an additional small hut. The buildings are almost all dwellings and have large storage spaces and fireplaces, while the southern hall also featured a smithy workshop and the middle hall housed a carpentry shop. The site also had ship-repair facilities but lacked outbuildings and structures for livestock; these would have had to graze outside throughout the winters that were relatively mild compared to those in Greenland.

Radiocarbon dating indicates L'Anse aux Meadows was built between 980-1020 CE; dates that are supported by the few artefacts found there, which stylistically range from the late 10th to early 12th centuries CE. These include a soapstone spindle whorl, showing the presence of some women, the butternut burls that confirm more southerly journeys, ship rivets, and a ringed pin of the Dublin Viking type which ties in with information from the sagas stating the explorers were Vikings with family connections in Ireland. L'Anse aux Meadows was unusually large for a Norse settlement and was capable of housing between 70-90 people in total. The houses are similar to those found in Greenland and Iceland, and Norse society's social spectrum is also mirrored here: the large halls befit a chieftain, the more modest halls his associate(s), while the remaining houses and huts were occupied by traders (who had their own ships) and their crews as well as perhaps a few slaves. This venture was no family affair but focused on business, although a few women were present for domestic chores. The absence of graves and the tiny size of the refuse middens indicate that L'Anse aux Meadows was probably occupied for less than ten years in total.

L'Anse aux Meadows gives us the distinct impression of having been a gateway location, a landing and launching pad at which expeditions arrived after a strenuous journey from Greenland. Supplies could be stored at the settlement until they were taken back to Greenland and beyond. It clearly matches the Straumfjǫrðr and Leifsbúðir from the sagas, each representing the Viking's main base in North America, which L'Anse aux Meadows undoubtedly was. With Norse Greenland only counting between an estimated 400-500 individuals at the time of the Vinland journeys, and L'Anse aux Meadows housing up to 70-90 people, there simply would not have been enough people to populate a second big settlement in America.

The Norse & The Natives

Despite all of its riches, America was not an uncontested land of plenty for the Norse. In all of the areas they visited, they seem to have bumped into groups of natives. As Peter Schledermann words it,

It was truly a momentous meeting between two worlds, east and west, the Old World and the New; a coming together of human beings separated at a distant and forgotten point in the history of human evolution. The Indians facing the Norse voyagers were descendants of people who had migrated through northeast Asia, crossed the Bering land bridge, and pushed south and east as the vast ice sheets melted away. (Fitzhugh & Ward, 191).

In Newfoundland and south-central Labrador, around 1000 CE, natives who may have been the ancestors of the Innu (Montagnais and Naskapi Indians) were present, while Newfoundland also housed the probable ancestors of the Beothuk Indians. At the same time, Dorset Paleo-Eskimos of the Late Dorset culture lived in northern Labrador and south-eastern Baffin Island. All of these cultures were skilled in terms of hunting and fishing and knew the land well.

In the sagas, the natives are referred to by the derogatory term skræling, whom the Norse are recorded trading with but also having hostile encounters with, such as the expedition of Karlsefni and Gudrid who first establish a good relationship with the native population but then mess it up when some of the natives are killed. Some Norse artefacts have been found in native settlements, which may indeed indicate direct contact, although these could also have ended up there as a result of scavenging. The exact nature of contact between the two groups may well have varied from one occasion to the next.

Vinland's Abandonment

The Norse settlement at L'Anse aux Meadows was seemingly abruptly abandoned, probably less than ten years after it was built, in the decades surrounding 1000 CE. As we can tell from the scarcity of artefacts found at the site, the crews appear to have brought all of their equipment and tools back home with them, and the whole abandonment affair comes across as well-planned. There is no visible chaos or disruption at the site, although two of the halls were burned, perhaps in a deliberate move by the Norse themselves as a symbolic ending to their adventures in Vinland. Whether this is true or whether something else entirely happened we may never know.

The small population size of Greenland and the enormity of the Vinland venture in contrast have already been mentioned, as has the incredible distances involved. Add to that the short sailing season of the northern Atlantic, and it means that maintaining regular shipping traffic would have been a huge headache or, rather, straight-up impossible. The fact that the land was also inhabited by scores of natives going about their business would have made North America's riches even less easily accessible. All in all, despite the interesting resources Vinland and its adjoining regions put on a mouth-watering display for the exploring Norsemen, the Vinland venture was probably too much of a hassle to be worth it. Europe, by contrast, was closer, held many more personal and political connections, and had similar enough sorts of resources so that traffic there would doubtless have taken priority over the Vinland journeys. It seems, though, that Vinland did not wholly give up its allure for a good few centuries after L'Anse aux Meadows was abandoned. Journeys to Labrador to gather timber seem to have continued on a regular basis at least until 1347 CE, for which year an Iceland account casually references this trip and treats it like a commonplace occurrence.