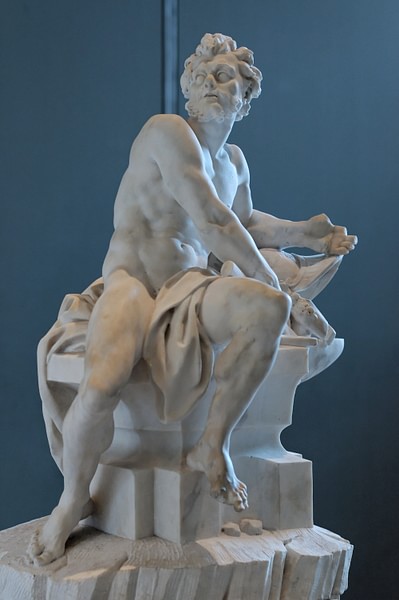

Vulcan or Volcanus was the Roman god of fire and forge, the equivalent of Hephaestus from Greek mythology. The son of Jupiter and Juno, he was the special patron of blacksmiths and artisans. As the god of the forge and the devastating fire of both the environment and nature (volcanoes), Vulcan was probably among the most dreaded of all the gods.

Like the other gods, Vulcan had a festival, the Vulcanalia (the Hephaestia) celebrated on 23 August, and a temple located outside Rome on the Campus Martius. For fear of fire (and for safety), most of his temples were located outside a city.

Birth & Family

Although she did not return his affections, Vulcan was, in the beginning, extremely fond of his mother, Juno. He often consoled her after one of their frequent arguments with Jupiter. In one story found in both Greek and Roman mythologies, Juno confronted Jupiter in another fit of jealousy. In anger, Jupiter dangled her out of the clouds by a golden chain. Vulcan attempted unsuccessfully to rescue her. Angry with his son's interference, Jupiter threw him out of heaven. Vulcan fell to earth for one full day and night, landing on the summit of Mount Mosychulus on the island of Lemnos. The severity of the fall left him lame and deformed, but his mother never inquired about his well-being. According to the Roman account, Vulcan withdrew to Mount Aetna where he established a great forge and partnered with the Cyclopes Bronte, Steropes, and Pyraemon.

A variation of this fall comes from Greek mythology. Hera was well aware of Zeus' wandering eye and wanted to give him a child of great strength and power, but at Hephaestus' birth, Hera found him small, swarthy, and ugly. Disgusted, she hurled him down the mountainside, disappearing into the sea. He was rescued by sea nymphs (one of them being the mother of Achilles, Thetis), who raised him in a cave where he learned to forge metal. In Hesiod's Theogony, "…Hera, angry, quarreled with her mate and bore, without the act of love, a son Hephaistos, famous for his workmanship…" (53)

Vulcan's ugliness and deformity prevented him from finding happiness in marriage. First, he was rejected (as were many others) by Minerva (Athena) who vowed never to marry. Next, as a punishment to Venus for her pride and rejection of all suitors, Jupiter married the goddess of beauty to the 'ill-favored' Vulcan, forcing her and her attendants – the Graces – to live with him in his cave in Mount Aetna. Of course, the marriage did not last, and she left him for the affection of others – one of them being his brother Mars. Lastly, Vulcan married one of the Graces, but, like the others, she deserted him. He did, however, have children (all of whom were considered monsters): among them were Cacus (slain by Hercules), Periphetes (killed by Theseus), and the wrestler Cercyon (possibly also killed by Theseus). Supposedly, he may have been the father of Servius Tullius, the sixth king of Rome.

The Golden Throne

Many of the stories and myths surrounding Vulcan can be found in the tales concerning Hephaestus. It is often difficult to differentiate between the two. One such story is of the golden throne. Partially in retaliation for how he was treated, Vulcan fashioned a beautiful golden throne for Juno, but it contained a number of hidden springs. If unoccupied, it appeared innocent, quite ordinary. However, if anyone sat on it, the chair closed up, and all attempts to escape its clutches would be fruitless. Juno was delighted with its beauty and delicate workmanship, but when she sat down, she found herself a prisoner. All attempts by the gods to free her failed. Finally, Mercury visited Vulcan in his cave and pleaded with him to return to Olympus and free his mother. Vulcan had vowed never to return to Olympus and flatly refused. Finally, Bacchus (Dionysus), the god of wine and revelry, appealed to Vulcan's better nature with a flask of wine. Vulcan consented and freed his mother. Afterwards, he returned to his forge and built magnificent palaces for each of the gods.

Birth of Minerva

In another Roman myth, Vulcan is associated with the birth of Minerva. Jupiter was in serious pain with a severe headache. All of the gods' attempts to help failed; even Apollo, the god of medicine, was unable to ease the pain. Finally, Jupiter appealed to Vulcan to open up his head with an axe. Vulcan quickly complied, and Minerva sprang forth, fully grown and clad in her armor. She would become known as the goddess of peace, defensive war, and wisdom. In the Greek version of the myth, it was Prometheus' idea for Hephaestus to use the axe. Reluctantly, the god of the sky knelt, and the fire god with one swift swing struck the center of the skull. Athena (Minerva) appeared. Her mother was said to be Metis. Homer wrote of her birth in The Homeric Hymns (No. 28):

It was Craft-filled Zeus himself who gave birth from his sacred head to her already in armor of war, all-gleaming; every immortal was gripped in awe at the sight. But quickly she leaped from his deathless head to stand.

(Homeric Hymns, 88)

Ovid's Metamorphoses

Vulcan, not Hephaestus, appears in both Ovid's Metamorphoses and Virgil's Aeneid. Ovid's (43 BCE to 17 CE) epic poem relates the history of Rome from its ancient beginnings to the death of Julius Caesar (100-44 BCE). It describes not only humanity's interaction with the gods but also heroes and heroines. In Book IV of the poem, Ovid writes about the celebration of a Bacchic festival when all women were excused from work. However, the daughters of Minyas decided not to attend the festival; they chose instead, to remain at their looms and exchange stories. Ovid writes:

... the Theban women cry; and perform the sacred rites as the priest bids them. Only the daughters of Minyas stay within, marring the festival, and out of due time ply their household tasks, spinning wool, thumbing the turning threads or keep close to the loom. (65)

After a while one of the daughters says,"…let us take turns in telling stories, while all the others listen" (65). The first daughter tells of the fated lovers Pyramus and Thisbe. Next comes Leuconoe who tells a tale of Mars and the faithless wife of Vulcan, Venus: "The Sun, with his central light guides all of the stars ... was the first to see the shame of Venus and Mars" (68). He relates what he had seen to Vulcan. "...Vulcan's mind reeled and the work upon which he was engaged fell from his hands." (68) The god of the forge fashioned a very thin net of fine links of bronze and spread it over a couch. "Now when the goddess and her paramour had come to this place, by the husband's art and by the net so cunningly prepared, they were both caught and held fast in each other's arms." (68) Vulcan opened the doors widely, displaying the two entwined lovers to the laughter of the gods.

Virgil's Aeneid

Although Virgil (70-19 BCE) was not pleased with his epic, Roman emperor Augustus (r. 27 BCE to 14 CE), who claimed to be a descendant of Aeneas, was ecstatic. The emperor believed that the poem demonstrated a final fulfillment of Rome's destiny. Virgil's Aeneid tells the story of the Trojan warrior Aeneas who escaped Troy in the final hours of the Trojan War. He eventually made his way to Italy where his descendants Romulus and Remus would one day build the city of Rome. In Book VIII of the poem, Aeneas and his fellow Trojans reach the Tiber River and the kingdom of Latium. Juno, still angry with Aeneas, arouses the ire of the Latium king and forces the Trojans into a war they did not want. Venus is concerned for her son Aeneas' safety and appeals to her husband Vulcan to make him weapons and armor.

"Venus, her mother's heart alarmed ... spoke to her husband, Vulcan, as they lay in their gold bedchamber. Breathing into the words all her divine allurement ... I ask no help of you for my unhappy people, make no demands on your skill and resource as a forger of weapons." (190)

She tells him how she owes a great deal to the sons of Priam. "Yet it is now that I'm asking a deity whom I reverence for arms, appealing to you on my son's behalf." (190) After he slept, Vulcan returned to his forge where the Cyclopes were working on Jupiter's thunderbolts and Mars' chariot. Vulcan told them:

Put aside all that work aside, pack up the jobs you're engaged on ... and turn your attention to this — the making of arms for a hot-blooded hero! Now there is need for your strength, your speediest work and your master-craftsmanship. (192)

They quickly went to work, and "They fashioned a shield of heroic size, to withstand by itself every missile the Latins can use" (193). Aeneas eyed every piece:

The formidable helmet with plumes like fountains of fire, the sword that would deal out doom, the breastplate of hard bronze … and the spear, and the shield's miraculous workmanship. (198)

However, on Aeneas' shield (being prophetic) he portrayed future events of Roman history. One such depiction is his portrayal of the Battle of Actium (31 BCE) where he showed Cleopatra: "The Fire-god had rendered her, pale with the shadow of her own death" (201).

Conclusion

Roman mythology gets lost within Greek literature. However, unlike the Greeks, Roman myths were written in prose, providing a sense of history and a foundation of all that was Roman. Some conciliation comes to the Romans in that the planets of our solar system bear the name of the Roman, not the Greek, gods – even the much-maligned Pluto. Unfortunately, Vulcan has no planet named for him, only the process of hardening rubber: vulcanization.