Wako (aka wokou and waegu) is a term used to refer to Japanese (but also including Chinese, Korean, and Portuguese) pirates who plagued the seas of East Asia from Korea to Indonesia, especially between the 13th and 17th centuries CE. Besides the disruption to trade, the devastation which befell coastal communities, and the many thousands of innocents who found themselves sold as slaves, the pirates caused significant tensions in diplomatic relations between China, Korea, and Japan throughout this period. Indeed, the pirates seriously damaged the reputation of Japan in the eyes of their East Asian neighbours in the medieval period. It was only after the warlord Toyotomi Hideyoshi (1582-1598 CE) had unified central Japan that the government was finally strong enough to effectively deal with the pirate scourge and put an end to their reign of terror.

Piracy on the High Seas

Wako translates as 'dwarf pirates' and although many were from Japan, the term was also indiscriminately applied to any mariners up to no good on the high seas and so could include pirates based on the coasts of Korea, Taiwan, and China, as well as Portuguese adventurers, to name but a few. There is even evidence that some pirates disguised themselves as Japanese to avoid detection as to where they sailed from. The Chinese called these pirates wokou and the Koreans waegu. Pirates had plundered ships across East Asia since at least the 8th century CE but it was the wako of the 13th century CE onwards that reached new depths of robbery, helped by the disruption in legitimate maritime trade which followed the Mongol invasions of Korea between 1231 and 1259 CE.

The most notorious pirate base was Japan's Tsushima Island (which also had legitimate ports) where there were plenty of easily-defended inlets. The island is rocky and mountainous so that residents struggled to provide enough food for themselves while the local feudal lords, the So, gained handsomely from sponsoring the marauders who seized goods on the high seas. Other important pirate bases in Japan were at Iki Island and Matsura.

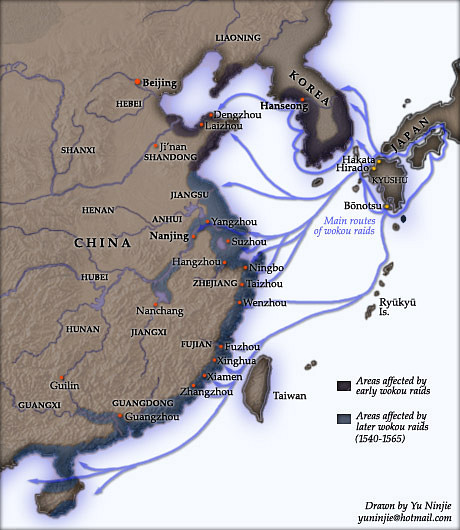

At their peak in the 14th century CE, hundreds of pirate ships plagued the straits between Korea and southern Japan and made four or five major raids on the southern Korean peninsula each year. Many pirates even made it their business to plunder ships and coastal ports on the western side of the Korean peninsula, right up the northern island of Kanghwa. In the 15th and 16th century CE the coast of China became another target area. Pirates stole anything of value (for example, precious metals, swords, armour, and lacquerware) but especially bulk goods like cloth, grain and rice being shipped as tribute to the Chinese emperor.

Pirates would raid ports and coastal settlements with fleets of up to 400 ships carrying raiding parties of 3,000 men. Although they were only lightly armed - the preferred weapon being swords - they did form disciplined armies and they met little organised opposition. As the wako often seized innocents to be sold as slaves to feudal lords or Portuguese slave-traders, many farming communities withdrew further inland, even if this meant that the best agricultural land was abandoned. The risks to the wako, aside from a vigorous defence by rightful owners, included execution if they were caught by the authorities in China, Korea, or Japan.

Identity

One of the difficulties for the medieval authorities (and modern historians) was to identify who exactly were wako. The pirates did sometimes engage in legitimate trade and, doubtless, some traders indulged in the odd act of piracy. Savvy pirates also seized official documents such as the Ming Dynasty (1368-1644 CE) tallies, or kango, which were designed to show the ship was a legitimate trader or tribute carrier. Part of the problem, too, was the pirates taking advantage whenever there was a decline in legitimate trade relations between China, Korea, and Japan, which happened frequently from the 12th century CE onwards depending on the internal events of each country. In this case, some feudal lords in all three countries were happy enough to endorse pirates as a means to increase their own revenues. It was also true that many wako, perhaps even the majority in the 16th century CE, were Chinese, many of them former traders disgruntled with the Ming government's domestic restrictions and taxes on trade. Korea also had its own share of indigenous pirates and another notable group were Portuguese traders who often collaborated with pirates in order to smuggle their goods into China.

The Korean Response

In the 14th century CE, the Koreans assembled a fleet of ships armed with cannons to face the pirate scourge with a notable victory credited to Choe Muson (d. 1395 CE) against a large pirate fleet at the mouth of the Kum River in 1380 CE. In the battle, Choe Muson was able to employ cannons thanks to his tireless efforts to develop gunpowder. However, despite several more victories over the years by the Korean navy, including direct attacks on Tsushima Island in 1389 CE and again in 1419 CE, when 700 suspected pirates were executed, the marauders could not be completely eradicated. The Korean government imposed harsh penalties, including execution, for those caught collaborating with pirates, but they needed the Japanese government to do more from their side, and they sent multiple embassies to the Japanese court for that specific purpose.

The Chinese Response

The pirates caused enough problems for the Chinese to warrant three separate diplomatic missions to the Japanese court to see what could be done about them. As with the Korean missions, though, the real problem was the Japanese had little control over the pirate's bases, even if the Chinese began to insist trade agreements between themselves and Japan would depend on the latter government's efforts to keep the pirates in check. Then, as noted, Chinese pirates grew in number, only adding to the problem of securing the seas for legitimate trading vessels. Several groups of pirates even won battles against Ming armies sent to disband them. The Yongle Emperor (r. 1403-1424 CE) of the Ming Dynasty expressed everyone's frustration when he declared:

Ships could not readily reach them, nor could spears or arrows readily touch them. We could not move them by bestowing benefits on them; nor could we awe them by pressing them with our might.

(Huffman, 50-1)

Realising the difficulty of constantly patrolling vast areas of sea and removing the pirates from their well-protected bases, the Chinese largely preferred a policy of robust defence. Accordingly, forts were built along the most vulnerable areas of coastline and all maritime trade was banned. Essentially, any unofficial vessel could now be identified as a pirate ship. By the mid-16th century CE, an even more determined action was taken against the pirates. The Chinese reformed their tax system and, instead of military service, payment could be made in silver. From this revenue a defensive naval force was assembled to patrol the coast and sink any pirates they came across. Consequently, serious defeats were inflicted on the pirates by forces led by two noted Ming generals, Hu Tsung-hsien (d. 1565 CE) and Chi Chi-kuang (d. 1587 CE), and the capture of the most-wanted pirate leader, Wang Chih in 1557 CE.

The Japanese Response

In the 14th century CE, the weakness of the central government, still not as yet in control of all the islands of Japan, meant the authorities could do little to control piracy, even when requested to do so by embassies from neighbouring countries, starting with Korea's first in 1367 CE.

In 1443 CE, the Japanese and Korean governments did finally get together, and they signed the Treaty of Kyehae which sought to legitimise trade between the two countries, particularly between Tsushima Island and the Korean ports of Tonnae, Ungchon, and Ulsan, thus removing part of the pirate's income. Unfortunately, the treaty was ripped up in 1510 CE following disturbances caused by Japanese traders in all three Korean ports. A new deal, but much more limited in scope, was drawn up two years later. The watered-down treaty worked for a while, but the pirates returned to raid Korean ports in a major offensive in 1544 CE.

By the end of the 16th century CE, the wako based in Japan were about to finally get their comeuppance. Toyotomi Hideyoshi, the military leader of Japan from 1582-1598 CE, was determined to wipe out piracy. Thanks to his unification of central Japan, he now had the muscle to attack the wako. Ever pragmatic, Hideyoshi also put many pirates to his own use, permitting their ships to legitimately trade from 1592 CE, provided they carried his own personal red seal, hence their common name of shuin-sen or 'red seal ships.' The same policy was carried out by his successor Tokugawa Ieyasu (r. 1603-1605 CE). Finally, the seas of East Asia had been (almost) freed of the pirates, but the damage to Japan's international reputation had already been done, and it would be Hideyoshi himself who far worsened it by attacking Korea between 1592 and 1598 CE, an invasion that included former wako and their ships.

This content was made possible with generous support from the Great Britain Sasakawa Foundation.