The War of the Sixth Coalition (1813-1814), known in Germany as the Wars of Liberation, was the penultimate conflict of the Napoleonic Wars (1803-1815). The Sixth Coalition, which included Russia, Austria, Prussia, the United Kingdom, Sweden, Portugal, Spain, and several German states, defeated the First French Empire and drove Napoleon into exile on the island of Elba.

Background

In 1812, the Napoleonic Empire reached its greatest geographic extent, stretching from the fields of Iberia to the banks of the Niemen River. 20 years of perpetual warfare had forged this 'Grand Empire' and had dramatically altered the balance of power in Europe. By 1812, Austria had been defeated by France four times and was reduced to a second-rate power. A similar fate befell Prussia, which lost half its territories after its humiliating defeat in 1806 and was subjugated to France.

Napoleon had become master of Central Europe, where he reorganized the German states into the Confederation of the Rhine, a French protectorate; a similar French client state, the Grand Duchy of Warsaw, was created in Poland in 1807, positioned threateningly on Russia's doorstep. Italy, too, was within Napoleon's sphere; the north, the Kingdom of Italy, was administered by Napoleon's stepson, Eugène de Beauharnais, while the southern Kingdom of Naples was ruled by his brother-in-law, Joachim Murat. France had annexed the Low Countries, invaded Iberia, imprisoned the pope, and forced Russia into an unfavorable alliance; by 1812, it seemed that Napoleon's mastery of Europe was unshakable. Few could have predicted that his empire would collapse less than two years later.

Of course, the first fractures in Napoleon's empire appeared prior to 1812. After Napoleon installed his brother, Joseph Bonaparte, on the Spanish throne, the Spanish and Portuguese revolted against French occupation in the bloody Peninsular War (1807-1814). The Iberian rebels proved resilient opponents, and Napoleon was forced to send hundreds of thousands of troops into the Spanish quagmire. Spanish resistance inspired further rebellions in Germany and Italy in 1809; though these revolts were crushed, they served as a reminder of the malcontent that festered beneath the surface. But none of these setbacks were quite as catastrophic as Napoleon's invasion of Russia, launched on 24 June 1812. The conflicting interests of Napoleon and Tsar Alexander I of Russia (r. 1801-1825) caused the Franco-Russian alliance to rapidly deteriorate. The breaking point came when Alexander pulled Russia out of the Continental System, Napoleon's large-scale embargo against the United Kingdom; Napoleon viewed this as a challenge to his authority. The goal of his invasion was to punish Russia and force it to rejoin the Continental System.

When Napoleon crossed the Niemen River into the Russian Empire, his Grande Armée was the greatest army that France had ever produced. It was comprised of 615,000 soldiers, 200,000 horses, and 1,300 cannons; slightly less than half of the troops were French (302,000), with the remainder (313,000) consisting of soldiers from across French-occupied Europe including Poles, Austrians, Prussians, Germans, Dutch, Italians, Spaniards, Portuguese, and others. Napoleon hoped to win a series of swift engagements against the Russian armies, thereby forcing Tsar Alexander to the negotiating table. However, the tsar's armies made a strategic retreat, luring Napoleon deep into Russian territories before finally offering battle on 7 September 1812, by which point the Grande Armée had lost over 100,000 troops to attrition. Though Napoleon won the ensuing Battle of Borodino and occupied Moscow one week later, he soon found himself in a precarious position; Moscow became consumed by a great fire, which deprived the occupying army of shelter and provisions.

Napoleon stayed in Moscow for 35 days, desperately hoping to reach a peace agreement with the tsar. When it became clear that no such peace was forthcoming, Napoleon ordered a retreat from Moscow on 18 October. The infamous Russian winter soon set in, and the Grande Armée was whittled down by attrition and the pursuing Russian army; by the time it limped back across the Niemen in early December, it had lost half a million troops and almost all its horses and cannons. Of the 100,000 survivors, most were unfit for battle, rendering the Grande Armée effectively destroyed. Napoleon left the remnants of his army in Poland and rushed to Paris, hoping to salvage the political situation.

The Sixth Coalition Forms

One of the surviving contingents of the Grande Armée was a Prussian corps that had been forced to fight for Napoleon under the terms of the Treaties of Tilsit (1807). Its commander, General Johann von Yorck, was a Prussian patriot who was eager to cast off French control, and, on 31 December 1812, he signed an armistice with the pursuing Russian army. Fearful of French retaliation, King Frederick William III of Prussia (r. 1797-1840) denounced Yorck's armistice. However, several Prussian officers and ministers followed Yorck's example, renouncing their allegiances to Paris. On 4 January 1813, the Russian army entered the capital of East Prussia, Königsberg (modern Kaliningrad), leading the ecstatic local authorities to declare war on Napoleon and begin raising an army. Frederick William realized his country was going to war with or without him, and reluctantly allied with the Russians on 28 February 1813 with the Treaty of Kalisch. The treaty stipulated that neither Prussia nor Russia could negotiate with Napoleon independently of the other.

The United Kingdom, which had been continually at war with France since 1803, was delighted by the prospect of a Sixth Coalition and resumed its traditional role as financier. The British seduced Sweden into joining the alliance by promising to support its acquisition of Norway from the Kingdom of Denmark-Norway, a Napoleonic ally; the Swedish regent was Crown Prince Charles John, formerly Jean Bernadotte, one of Napoleon's marshals. For the time being, Austria remained neutral. Though it was eager to see the downfall of Napoleon, Austria was suspicious of Russian intentions and had no desire to see French hegemony replaced with Russian domination. Austria compromised by offering an armed mediation, promising to join the coalition if peace talks failed. In the meantime, the Austrians mobilized 200,000 troops from its Landwehr militia.

Napoleon, meanwhile, arrived in Paris on 18 December 1812, the day after it had been made public that the Grande Armée was no more. The shock that the French populace must have felt at this revelation would have been heightened when Napoleon immediately announced that he was raising a new army of 150,000 men to beat back the many enemies gathering against him. Though most of his veteran soldiers were either occupied with the war in Spain or buried beneath the snow of Russia, Napoleon managed to gather 150,000 men by April 1813. However, most of these troops were young and inexperienced conscripts, and the army lacked cavalry; Napoleon had lost almost all his horses in Russia, and new cavalry horses took a while to train. Despite its inadequacies, this army would have to suffice. In April, Napoleon received word that the Russo-Prussian army had invaded Saxony, whose king remained a staunch French ally. On 25 April, Napoleon took command of his new Army of the Main, leaving his wife, Empress Marie Louise, as regent in Paris; since Marie Louise's father was Emperor Francis I of Austria, Napoleon hoped this gesture would dissuade the Austrians from joining the war.

Spring Campaign & Armistice

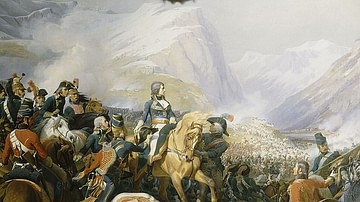

On 1 May 1813, Napoleon crossed the Saale River, rushing to the defense of Saxony. That same day, one of his most trusted marshals, Jean-Baptiste Bessières, was struck and killed by a cannonball while scouting the enemy positions, a heavy blow to French morale. On 2 May, Napoleon clashed with a 90,000-man Russo-Prussian army at the Battle of Lützen; although Napoleon won the engagement, the lack of cavalry prevented him from completing his victory by chasing down the Allied army. The Allies retreated to Bautzen, where Napoleon attacked them again on 20-21 May; the Battle of Bautzen was another French victory, though Napoleon was again unable to destroy the Allied army. The Allies withdrew to Silesia, leaving the road to Berlin wide open. However, when French Marshal Nicolas Oudinot was sent to seize the Prussian capital, he was defeated by Prussian General Friederich von Bülow at the Battle of Luckau (4 June).

Tensions were high amongst the Allies, as both Prussia and Russia blamed one another for the defeats at Lützen and Bautzen. Desiring more time to reinforce and resupply, the Allies asked Napoleon for an armistice; surprisingly, the French emperor agreed, and the Pleischwitz Armistice was signed on 4 June and would last until 18 August. Napoleon, who had lost 40,000 men in the campaign so far, saw the armistice as a great opportunity to replenish his forces. But in hindsight, the armistice was a bad move on his part since it deprived him of his chance to capitalize on his victories and allowed the Allies more time to gather their forces. On 26 June, Austria made good on its promise of mediation as its foreign minister, Prince Klemens von Metternich, met with Napoleon in Dresden. Metternich's terms for peace required Napoleon to relinquish control over Germany, Poland, and Italy and restore Prussia to its pre-1806 status; when Metternich refused to budge on these issues, Napoleon became furious. "So, you want war?" the emperor raged, "I have already annihilated the Prussian army at Lützen; I have defeated the Russians at Bautzen; now you want to have your turn. Very well, we shall meet at Vienna." (Mikaberidze, 564)

Once Napoleon rejected Metternich's Dresden proposals, Austria joined the Sixth Coalition on 27 June. The leaders of the coalition met at Trachenberg to formulate a strategy. They decided to field half a million men who would be deployed in three major armies: the 230,000-man Army of Bohemia was commanded by Austrian Field Marshal Karl Philipp, Fürst von Schwarzenberg; the 140,000-man Army of North Germany was commanded by Swedish Crown Prince Charles John; and the 105,000-man Army of Silesia was led by Prussian General Gebhard Leberecht von Blücher. Each army was multinational, designed to force cooperation between the member nations. The coalition also introduced the Trachenberg Plan as a strategy to defeat Napoleon. The plan called for the Allied armies to avoid engaging Napoleon directly and to instead increase pressure on the French flanks and communications. If possible, the Allies were encouraged to destroy the forces led by Napoleon's marshals when they were sent out on separate missions. The plan was primarily authored by Charles John, who, as a former French marshal himself, was familiar with Napoleon's strengths and weaknesses.

Dresden & Leipzig

When hostilities resumed on 18 August, the Allies put their Trachenberg Plan into effect. Marshal Oudinot, who was once again sent to seize Berlin, was intercepted and defeated by Charles John, his former comrade, at the Battle of Grossbeeren (23 August). Three days later, French Marshal Étienne Macdonald was defeated by Blücher at the Battle of Katzbach. However, Napoleon exploited an error made by Schwarzenberg and attacked the Army of Bohemia at the massive Battle of Dresden (26-27 August). Though Napoleon won the battle and inflicted 30,000 Allied casualties, he was once again prevented from achieving a decisive victory due to his lack of cavalry. Despite this hiccup, the Allies continued to follow the Trachenberg Plan; when French Marshal Michel Ney was sent to capture Berlin, he walked into a trap set by Charles John and was defeated at the Battle of Dennewitz (6 September).

The Allied strategy was working, as the defeats suffered by his marshals had cost Napoleon tens of thousands of troops, while his remaining soldiers were suffering from a lack of provisions after the Allies began targeting French supply lines. Napoleon chased the armies of first Blücher, then Charles John, but both commanders successfully avoided battle. To make matters worse for Napoleon, his closest German ally, Bavaria, switched sides and joined the coalition on 8 October. Frustrated, the French emperor withdrew to Leipzig, where he hoped to make a stand.

The Battle of Leipzig, also known as the Battle of the Nations, was fought from 16-19 October 1813, and involved 190,000 French and 380,000 Allied troops, making it the largest battle in European history prior to the First World War. The first day of fighting ended in a stalemate, but by the 18th, the odds were clearly against Napoleon; his Saxon and Württemberg troops switched sides, and the Allies enjoyed a steady stream of reinforcements. That night, Napoleon ordered a retreat, but his army became congested as it attempted to cross a single bridge over the Elster River. During the confusion, a French corporal blew up the bridge prematurely, stranding thousands of French troops on the wrong side of the river, where many were captured. Some tried to swim across the river but were drowned, including the Polish national hero Prince Józef Poniatowski. In all, the French lost 60,000 casualties at Leipzig, and the Allies lost around 50,000.

Invasion of France

Napoleon's defeat at Leipzig destroyed any possibility that Napoleon could win the war. On 18 November, the Allies declared the Confederation of the Rhine to be dissolved, and the German states turned against their old master by providing the Allies with troops. Joachim Murat, eager to retain his Kingdom of Naples, switched sides and threw his lot in with the coalition. To make matters worse, Napoleon's brother Joseph had lost the Battle of Vitoria (21 June 1813) against an Anglo-Spanish-Portuguese army led by Sir Arthur Wellesley, Duke of Wellington. By the end of the year, Bonapartist Spain had fallen, and Wellington's army had invaded Southern France. In February 1814, Bordeaux surrendered to Wellington without a fight and hoisted the flag of the old Bourbon Dynasty.

In November 1813, Metternich once again proposed terms for peace. Under the so-called Frankfurt Proposals, Napoleon would be allowed to retain his throne, and France would be able to keep Belgium, Savoy, and the Rhineland, the original conquests of the French Revolution (1789-1799). Metternich stressed that these were the best terms Napoleon would get. It was a hard pill to swallow, forcing Napoleon to relinquish a career's worth of conquests; he delayed answering for too long, and lost the opportunity when the Allies withdrew the offer in December. Napoleon then set about preparing the defense of France; hoping to rouse the patriotic spirit of the Revolution, he allowed the previously banned republican anthem La Marseillaise to be played in the streets and resurrected the old Jacobin refrain "La Patrie en Danger!" ("the Fatherland is in danger!"). However, after two decades of war, most Frenchmen were apathetic to their emperor's cause. Most of the troops Napoleon was able to scrounge together were conscripts, many of them boys; these boy-soldiers were nicknamed the 'marie-louises' after the young empress who had signed the conscription order.

The Allies invaded France in January 1814, and Napoleon fought back with determination. The emperor's plan was to keep the Allied armies divided and wear each one down with a series of quick attacks. On 29 January 1814, he defeated Blücher's Army of Silesia at the Battle of Brienne, where Napoleon had studied as a boy. Napoleon continued to target Blücher's army, winning a series of victories in his so-called Six Day Campaign (10-15 February), which is considered by some historians as one of his most impressive campaigns. However, the advance of Schwarzenberg's Army of Bohemia toward Paris forced Napoleon to change tactics. On 20 March, he attacked Schwarzenberg's much larger army at the Battle of Acris-sur-Aube and was defeated; three days later, the Allies intercepted a letter from Napoleon to Marie Louise that detailed crucial French military intelligence.

The Allies arrived at Paris on 30 March 1814; the city was defended by French marshals Auguste de Marmont and Édouard Mortier. The ensuing Battle of Paris resulted in bloody and desperate fighting which ended on 31 March, when the marshals accepted parleys from the Allies. A provisional government, formed by Charles-Maurice de Talleyrand and Joseph Fouché, began negotiations with the Allies and convinced them to restore the Bourbon Dynasty to the French throne. Napoleon, meanwhile, was at Fontainebleau, where his marshals urged him to abdicate for the good of France. On 2 April, Napoleon sent his advisor, Armand de Caulaincourt, to Paris, with an offer to abdicate in favor of his infant son. The Allies considered the offer until 4 April, when Marshal Marmont arrived at the Allied camp and surrendered his entire command; afterward, the Allies demanded nothing less than Napoleon's unconditional abdication, which was given on 11 April 1814.

Aftermath

In the Treaty of Fontainebleau, Napoleon renounced the throne of France in return for sovereignty over the island of Elba and an annual income of 2 million francs. On 20 April, Napoleon said a heartfelt goodbye to his Imperial Guard at Fontainebleau before being escorted by Allied troops to the ship that would take him into exile. King Louis XVIII arrived to take the French throne, and hostilities were officially ended with the Treaty of Paris, signed on 30 May 1814. France was reduced to its 1792 borders, and the victorious powers met at the Congress of Vienna to redraw the map of Europe in a post-Napoleonic world. But the Napoleonic Wars were not quite over; on 20 March 1815, Napoleon would escape from Elba and retake his throne. In the climactic period of the Hundred Days that followed, Napoleon was defeated at the Battle of Waterloo (18 June 1815) and exiled to the island of St. Helena, this time for good.