Warren Hastings (1732-1818) was appointed the Governor of Bengal by the British East India Company (EIC) in 1772 and became its first Governor-General in India from 1774 to 1785. Under his tenure, the EIC ruthlessly expanded its territory both in terms of conquest and through treaties of alliance with Indian princely states.

Hastings had a new vision for how India should be ruled, and it involved including Indians in their own forms of government and judiciary, but the chaotic reality of a post-Mughal India now beset with rivalries between princely states and the rapacious presence of EIC traders and its military meant the governor's plans came to naught. A flashy spender when back in England, Hastings was accused of corruption during his time in India, a charge he was ultimately acquitted of. Made a target of by the great political commentator Edmund Burke (c. 1729-1797), Hastings was a divisive figure whose own tumultuous career reflected the complex questions the British parliament faced in the late 18th century: How might the EIC be better controlled and how should India be governed if it became a colony in the fullest sense.

Early Career

Warren Hastings was born in Churchill, Oxfordshire, England, on 6 December 1732 into a family that had once been prosperous in Tudor times but was now rather down at heel. William's mother died young, and his father abandoned him to go and live in Barbados. Consequently, William was looked after by one of his uncles and sent to Westminster School in London.

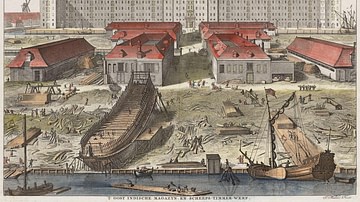

Hastings joined the mighty East India Company as a clerk or 'writer' and sailed for India in 1750. In 1757, Hastings served as a volunteer in the EIC army commanded by Robert Clive (1725-1774) which won the Battle of Plassey against the Nawab (ruler) of Bengal. Impressed by the younger man, Clive secured Hastings a new position at Murshidabad in West Bengal. Serving from 1758 to 1761 as the EIC's representative at the court of the Nawab of Bengal, he supervised a lucrative trade in such goods as opium, salt, tobacco, and timber. He was appointed to the EIC's Council of Bengal in 1761 and served until he fell out with his fellow council members over policy matters. The historian W. Dalrymple gives the following character description of Hastings: "Plain-living, scholarly, diligent, and austerely workaholic, he was a noted Indophile" (ix).

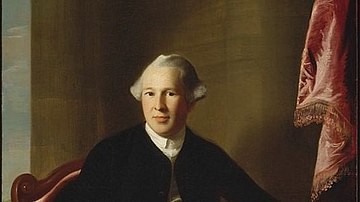

In 1765, Hastings returned to England in triumph having enriched himself on India's resources, like so many other successful EIC figures had done. He was able to buy a new and bright red carriage and revive the use of his family's ancient coat of arms as part of its ostentatious decoration. Sir Joshua Reynolds was commissioned to paint Hastings' portrait. Unfortunately, Hastings income could not quite match his lifestyle, and he soon found himself in debt. The lure of India and its riches meant he returned as an EIC council official, this time in Madras in 1769.

EIC Governor-General

In 1772, Hastings' star was on the rise once more and he was made the Governor of Bengal. Hastings had to face the consequences of a widespread famine which had hit Bengal the previous year, but he did not let this and the resulting massive loss of life cause too much of a dent in EIC revenue. The governor blamed the local rulers for the chaos and horrors of a famine that killed a third of the peasant population in some areas. Tax collections were, noted Hastings in his curious two-sided view of Indian affairs, "violently kept up to their former standards" (Dalrymple, 220). The new governor did build public granaries to try and ensure no future famine would ever cause such loss of life.

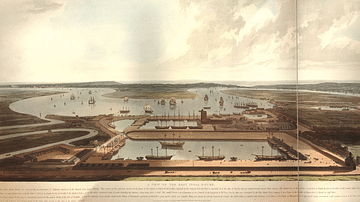

In 1774, he was appointed the Governor-General of the three EIC presidencies of Bengal, Madras, and Bombay. The latter position was created by the 1773 Regulating Act, which, in response to concerns over its finances, powers, and corruption, obliged the EIC to restructure its management hierarchy. Hastings was thus the first Governor-General, and he and his board of four advisors held sway over the EIC in India. There was much to do, Hastings remarking that the EIC's affairs were "a confused heap of undigested materials" (Mansingh, 170). Hastings oversaw a drive to stop corruption amongst EIC traders, particularly the long-standing convention of accepting gifts from interested parties in EIC contracts. To discourage the taking of bribes, all private trade by EIC employees was prohibited, and salaries were increased. He also attempted to stop the worst of the abuses carried out by local EIC agents on indigenous peoples. Hastings moved the administrative centre of Bengal from the Nawab's court to direct EIC supervision in Calcutta. He created an efficient company postal system and had a full land survey undertaken in order to create more accurate maps of India.

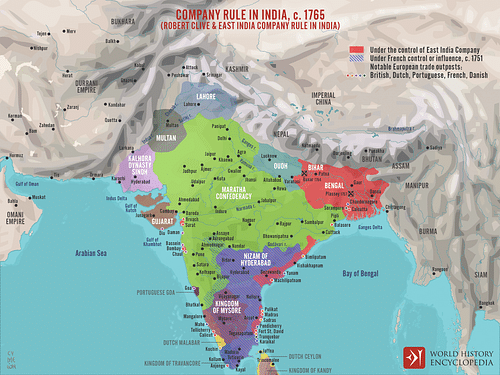

After the successful but expensive military victories commanded by Robert Clive, Hastings wanted the East India Company to achieve further territorial expansion by a more cost-effective method. Hastings made several treaty arrangements with independent Indian princes, like the rulers of Awadh (aka Oudh) and Banaras, whereby administration and tax collection were left to local bodies and the EIC could concentrate on what it had been formed to do: trade. This policy, often called one of Subsidiary Alliances, saw the EIC grow enormously.

Independent rulers saw the advantages of the EIC's army as a protective force against potential threats from rivals and rebellions; the ruler of Awadh, for example, hired out an EIC army for a fee and so was able to defeat his enemy the Rohillas. The rulers were sometimes expected to pay for the privilege of protection in an arrangement that many of Hastings' critics back in England considered no better than extortion. The same critics also pointed out that enemies of princely states were not necessarily enemies of the EIC and so such wars were not a good use of the Company's military arm. Hastings could respond that he was at least increasing the EIC's profitability at a time when it was not doing well financially, especially in Bengal.

The British-controlled territory in India kept on expanding since Hastings in Calcutta could not directly influence the governors of the two other EIC presidencies (administrative regions) of Bombay and Madras. Both governors there were involved in wars, the former with the Marathas and the latter with Mysore in southwest India. The Four Anglo-Mysore Wars (1767-1799), in particular, resulted in yet more territories being gobbled up by the EIC.

Another feature of Hastings' tenure was to try and replicate the system of rule the Mughal Empire had imposed over parts of India. Rather than have EIC officials rule directly, Hastings wanted Indians to rule themselves and follow their own justice systems but ultimately be loyal to the EIC. The historian J. Wilson describes Hastings' plan as "an intellectual fantasy" (131) since the Mughal apparatus of empire no longer existed in any meaningful form and other top EIC officials were happy enough to rule by the sword and extort the population and rulers for whatever they could get away with.

Hastings was a little more sympathetic than his predecessors towards the millions of Indians over which the EIC now ruled and to foreigners in general. Unlike his predecessors such as Robert Clive who spoke only English, Hastings at least had learnt Persian, then the EIC's official language, Bengali, and Urdu. Hastings arranged for several important Indian works to be translated into English. He supported the Asiatic Society of Bengal (founded in 1784) which promoted what was then called Oriental Studies. In one of those curious quirks of institutional racism in British India, no Indians could join the society until 1829, but it did at least promote a European interest and consideration of Indian culture, religion, and art in a period when most colonizers had little time for or anything positive to say about the peoples they were exploiting.

One episode was particularly damaging to Hastings' reputation, the execution of Maharaja Nandakumar Bahadir (aka Nuncomar). In 1775, seeking to exploit the divisions in the EIC Council in Bengal and strengthen his own position in Bengal while diminishing that of the governor, he accused Hastings of taking bribes in return for political favours. Found guilty of forgery (committed several years earlier) by a panel of British judges, Nandakumar was hanged on 5 August in Calcutta. It was the first time the EIC had ever hanged anyone for such a minor crime, and Hastings' ruthlessness did not sit well with his other more conservative policies. Hastings continued to have problems, too, with rivals on the Bengal Council. He even fought a duel with one of them, Philip Francis, in 1780. Francis' shot missed while Hastings' hit his opponent's rib, but Francis survived.

The Nabobs & Impeachment

In 1785, Hastings returned to England, but he received a reception far from the colonial hero's welcome he perhaps anticipated. He was attacked for corruption and acts of cruelty during his time in India, notably by the Whig politician Edmund Burke who described Hastings and his like as 'nabobs' (although he did not himself coin the phrase), a corruption of the Indian term nawab and meant to deride their grasping greed and the new flash lifestyle they enjoyed in England from their ill-gotten gains. Hastings was held up as the worst example of this particular species of nouveau riche. Even worse in Burke's eyes, Hastings had sullied the name of Britain in India and on the international stage by stealing on a grand scale and acquiring for the EIC "all the landed property of Bengal upon strange pretences" (Wilson, 132). Burke received his inside information from none other than Philip Francis, the man Hastings had shot five years before.

Hastings may not have done any more or less than others in his position had done, but he was prone to lavish spending both on his household and other indulgences such as the famous red-tinged diamond he brought back from the subcontinent. Even his wife Marian was often to be seen decked out in such an obscene quantity of diamonds she was known as the 'Indian princess'. Hastings likely saw his spending as a just reward for a career that had successfully blended service for the Company with increasing his own bank accounts. Hastings was, though, a victim of timing. Prominent members of the British Parliament were aghast at lurid tales of the EIC's policies in India, and many sought to bring the company under much greater scrutiny and control. There were others, though, who profited greatly from the EIC, some MPs were even in its employ. The monarchy, too, was not in favour of infringing on private property. Hastings became a ball struck back and forth between these two sides as the British establishment pondered at its leisure what exactly it should do with the trading monster that the EIC had become.

The 1784 India Act restructured the top management of the EIC, and Parliament installed one of its representatives on the now all-powerful Board of Control. It was a small but significant step towards greater state control, but the EIC remained independent in many ways. There was still the fundamental question to be answered: why was the EIC conquering lands when it was not actually a state? A secondary question was even more difficult to answer: By what moral code did the EIC operate when it had nobody to answer to but its shareholders? These questions were posed in a cultural context that saw philosophers influence politicians in Britain with their thoughts on the importance of individual liberty, government by consent, and rule through justice. It seemed the EIC was not bothered one iota by any of these considerations when conducting trade with and governing Indians in the name of Britain. In a certain sense, Hastings became a sort of test case for how the EIC might also be examined and dealt with. It was somewhat ironic that Hastings had been sent out to India to reduce corruption and here he was held up as the very worst example of it.

Hastings was impeached by Parliament in 1787, charged with "high crimes and misdemeanours". The charge – based on Hastings' selling of EIC offices, taking of bribes and protection money, accumulation of personal wealth, and ultimate responsibility for acts of violence by EIC employees – was heard in Westminster Hall under the auspices of the House of Commons, but the House of Lords, Parliament's upper chamber, acquitted Hastings of any wrongdoing during his time in India, a decision that took seven years to reach. It had taken a very long time, but the British establishment had finally realised that although all of the charges against Hastings were based on a reality, he was perhaps not the best choice of target to go after in a court of law. It was the EIC which should have been on trial, not one of its more moderate executives. The EIC this time escaped, but the spotlight had been turned upon its dark deeds, and in another half century or so, its time would come when it was finally dissolved and its wealth and empire taken over by the British state.

Times changed again, and by the 19th century and near the end of his life, Hastings was looked upon proudly (in Britain) as one of the chief architects of British imperialism in India. Not only was Hastings' reputation rehabilitated but he also had the satisfaction of restoring his family's fortunes when he bought back the ancestral home at Daylesford in Gloucestershire, which the Hastings family had been obliged to sell in 1715. Hastings lived out his retirement there and died in 1818, aged 85.