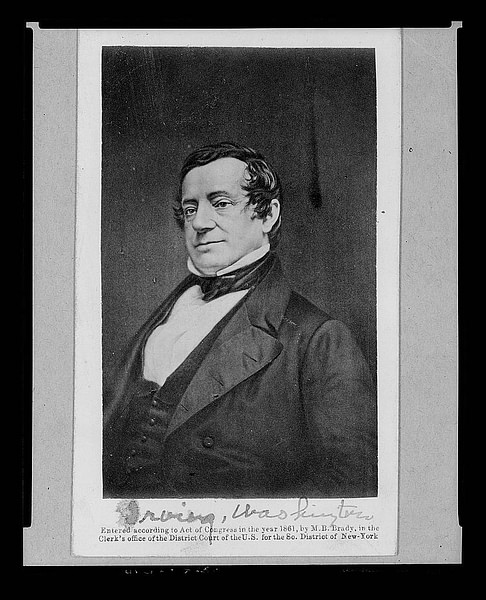

Washington Irving (1783-1859) was an American author, essayist, and diplomat best known for his short stories The Legend of Sleepy Hollow and Rip Van Winkle. He was the first professional American author and also the first to achieve an international reputation.

He influenced such notable 19th-century authors as Nathaniel Hawthorne, Herman Melville, Edgar Allan Poe, and Walt Whitman; "The unorthodox fantastical sensibilities he displayed in his tales … set the stage for the Romantic and Gothic writers that followed him" (Bradley, vii). Many of the characters in Irving's stories have become household names: Rip Van Winkle, Ichabod Crane, and, of course, the Headless Horseman. He was a notable innovator, with a sense of style and form that kept his writings fresh, and his short stories and sketches have endured as the first fictional chronicles of the American experience.

Early Life

Named after General George Washington (1732-1799), Washington Irving was born in New York City on 8 April 1783, five days after the signing of the Treaty of Paris, ending the American Revolutionary War with Great Britain. He was the last of eleven children born to a prominent Manhattan merchant family. His father, William, was Scottish-born while his mother, Sarah, was English-born. There is little evidence to suggest that Irving attended either public or private school. As a child he read widely in English literature: William Shakespeare, of course, but also the English essayist Joseph Addison as well as the Irish novelists Laurence Sterne and Oliver Goldsmith.

In 1804, he showed signs of tuberculosis, so his brothers sent him to Europe for two years where he kept extensive journals. Upon his return to the United States, he studied law under Judge Josiah Hoffman and passed the bar. Although he would practice law for a short time, he preferred to write. His extensive travels throughout England and the United States fueled his love of writing: "I was always fond of visiting new scenes and observing strange characters and manners. Even when a mere child I began my travels and my tours of discovery into foreign parts and unknown regions of my native city to the frequent alarm of my parents" (quoted in Bradley, 9). Irving came from a very close-knit family who encouraged his writing; this closeness was something that would remain part of his life. Writing was commonplace in the Irving home. For recreation, his brothers wrote poems and essays. His brother Peter had a newspaper The Morning Courier, and at the age of 19, using the pseudonym Jonathan Oldstyle, Irving wrote a number of satirical essays on the theater and New York society. In many of his writings, Irving often used pseudonyms, such as Jonathan Oldstyle or Geoffrey Crayon.

First Major Work: A History of New York

Irving and his brother William started a short-lived (one-year) satirical newspaper Salmagundi. Published anonymously, it contained sketches, essays, and commentaries on politics and drama. It supposedly bestowed on New York City the nickname of Gotham. In 1808, Irving began writing A History of New York, from Beginning of the World to the End of the Dutch Dynasty by Diedrich Knickerbocker. With the book's publication in 1809, Irving became an instant celebrity – the book was even sold in England. His book reminded readers that long before the city was named after the Duke of York, it had a proud history. The Dutch were the original European settlers of the area naming it New Netherland with New Amsterdam as its capital. It was only renamed New York when the English took over the colony in 1664. Irving brought "the settlement to vivid, charming life, and A History of New York made the traditions and folkways of the Old Dutch settlers popular (Bradley, xi).

Life in Europe

During the War of 1812, Irving was the editor of the Analectic Magazine, which published biographical sketches of American naval heroes and essays from English periodicals. Near the end of the war, he was named a colonel in the New York State militia. But, in May of 1815, with the war over, he left for England and would not return to the United States for 17 years. Initially, he worked for his brother Peter's export business in Liverpool until it went bankrupt in 1818. The failure of the business, together with the death of his mother, caused Irving to fall into depression, but Irving turned his grief into writing. The result was The Sketch Book, published under the pseudonym of Geoffrey Crayon. The Sketch Book contained the Knickerbocker stories of Rip Van Winkle and The Legend of Sleepy Hollow. Although some give credence to Irving's exposure to German folktales, most writers believe the stories were inspired by Irving's travels through the Catskill Mountains and Hudson River Valley.

In 1819, Irving sent The Sketch Book to the United States for publication in installments, but at the suggestion of Sir Walter Scott (1771-1832), who had admired A History of New York, it was published in one volume in England. The publication of The Sketch Book in England made Irving famous. Aside from the short stories of Rip Van Winkle and Sleepy Hollow, it was part travelogue, part story anthology, and part personal essays. It marked the emergence of the short story as a literary form. Crayon, the book's narrator, was an American in England searching for his roots, visiting many of the 'sacred sites' from Stratford-upon-Avon to Windsor Castle, but Irving, in the guise of Crayon, criticized English travelers for their depiction of America. He called out snobs, social climbers, and fakes. In The Sketch Book, "we find his most supernatural imaginings, and his most unforgettable characters, tucked quietly among descriptions of idylls in the English countryside." (Bradley, viii) Many Englishmen were amazed that an American could write about England as he did.

Irving, as Geoffrey Crayon, also related his affinity for the holidays, especially Christmas in England, writing: "Nothing in England exercises a more delightful spell over my imagination, than the lingerings of the holyday customs and rural games of former times." (The Sketch Book, ch. Christmas) To him, it was Christmas that awakened the strongest and most heartfelt associations:

The English, from the great prevalence of rural habits throughout every class of society, have always been fond of those festivals and holydays which agreeably interrupt the stillness of country life. (ibid)

Even the poorest of cottage "welcomed the festive season with green decorations of bay and holly" (ibid). Although they were fond of the religious and social rite of Christmas, Irving was heartbroken to see that due to modern refinement, many of the games and ceremonies of the holiday have disappeared, and "The world has become more worldly" (ibid). However, despite this, he felt that it was still a period of delightful excitement. As he rode along the country lanes, "it seemed to me as if every body was in good looks, and good spirits" (ch. The Stage-Coach).

Awakening on Christmas morning, "I heard the sound of little feet pattering outside of the door" (ch. Christmas Day). He opened the door and "beheld one of most beautiful little fairy groups that a painter could imagine" (ibid). Irving found that everything "conspired to produce kind and happy feelings in this stronghold of old-fashioned hospitality" (ibid). A servant escorted him to a small chapel for family prayer and a Christmas carol. The family then went to church in an old building of gray stone. A parson gave a "most erudite sermons on the rites and ceremonies of Christmas, and the propriety of observing it, not merely as a day of thanksgiving, but of rejoicing" (ibid). Later, dinner was served in a great hall. The dinner table was loaded with good cheer "and presented an epitome of country abundance" (ch. The Christmas Dinner). In closing Irving wrote:

If I can now and then penetrate through the gathering film of misanthropy, prompt a benevolent view of human nature, and make my reader in good humour with his fellow beings … I shall not then have written in vain. (ibid)

During his 17 years away from the United States, besides The Sketch Book, he wrote Bracebridge Hall (1822) and Tales of the Traveller (1824). Another Geoffrey Crayon narration, Bracebridge Hall was a collection of 50 stories and essays. It was a tribute to the old-fashioned English country, but Irving felt that it was a poor follow-up to The Sketch Book. Two years later, Tales of the Traveller was published, with Crayon narrating again. Two of the best-known stories from this collection are The Adventure of the German Student, a nod to the horror tradition, and The Devil and Tom Walker, a story of greed in American business dealings. It was among the first deal-with-the-devil stories. Both stories demonstrated his flair for fantasy.

As a writer, Irving had won great success in England and acquired great respect for the country and its heritage:

...Europe held forth the claim of storied and poetical association. There were to be seen the masterpieces of art, the refinements of highly-cultivated society, the quaint peculiarities of ancient and local custom"

(The Sketch Book, The Author's Account on Himself).

Irving added that while the United States was full of promise, Europe was rich in the treasures of age. With both books not up to the standards of his previous works, Irving was at a loss. He accepted an invitation from the American minister to Spain to serve as an attaché at the legation. He was asked to translate Martín Fernández De Navarrette's compilation of the accounts of Christopher Columbus, including Columbus' own lost journals as copied by an earlier historian. In 1828, with the assistance of the American consul in Madrid, Obadiah Rich, Irving published his A History of the Life and Voyages of Christopher Columbus. However, instead of a translation, it was Irving's own work. From his time in Spain, he wrote A Chronicle of the Conquest of Granada (1829), Voyages and Discoveries of the Companions of Columbus (1831), and Tales of the Alhambra (1832).

Back in the US

In 1829, Irving was appointed secretary to the American legation in London. Three years later, Irving returned to the United States, but having been in Europe for the last 17 years, many believed he was too Europeanized. To reacquaint himself with a changing America, he turned to traveling the American West, producing A Tour on the Prairies (1835), a horseback ride across what would become the Oklahoma territory; Astoria (1836), a look at the John Jacob Astor's fur-trading colony; and The Adventures of Captain Bonneville, USA (1837), an account of a Frenchman's exploration of the Rockies.

After returning to New York, he bought a home for himself and his family near Tarrytown, named Sunnyside, along the Hudson River north of the city. He only left briefly when President John Tyler (1841-45) named him minister to Spain for four years. During his time at home, he continued to write, publishing a collection of stories and essays in Wolfert's Roost and Other Papers (1852). In 1851, he began his Life of George Washington, a five-volume undertaking. He traveled to battle sites, read old newspapers, and visited libraries. The first volume was published in 1855. After finishing the fifth volume, he collapsed and died of a heart attack on 28 November 1859.