The steam engine developed by the Scotsman James Watt (1736-1819) from 1769 was much more efficient in terms of power and fuel consumption than earlier models, and it significantly increased the possible uses for this key invention of the Industrial Revolution (1760-1840).

Watt did not invent the steam engine, nor was he solely responsible for the technical developments that bear his name, but he was the driving force behind making the engine the favourite power source for many factories, mines, agricultural machines, and modes of transportation. Watt and his business partner Matthew Boulton (1728-1809) made and sold almost 500 steam engines before their patent ran out in 1800 and other investors took on the mantle of further improving the power and efficiency of the steam engine.

The Early Steam Engines

The steam engine was an invention which evolved over time as successive engineers made it more and more efficient and adapted it for wider practical and cost-effective uses. The primary aim was to develop a machine that could replace traditional sources of power such as human and animal muscle, wind, and water.

The steam engine was first developed as a means to pump mine shafts free of flood waters, allowing deeper mining to take place. The first steam pump was patented by Thomas Savery (c. 1650-1715) in 1698. Thomas Newcomen (1664-1729), an ironmonger from Dartmouth, perfected his more powerful steam pump to drain coal mines of water in Dudley in the Midlands in 1712. The Newcomen engine was still not very fuel-efficient, not a serious problem in coal mines where there was obviously plenty of coal, but a disadvantage if steam engines were to be used elsewhere like tin mines and factories. Another problem was that Newcomen's engine was not particularly powerful. Fortunately, the steam engine involved many different parts, and each of these was developed over time by different inventors to make it more powerful and more efficient.

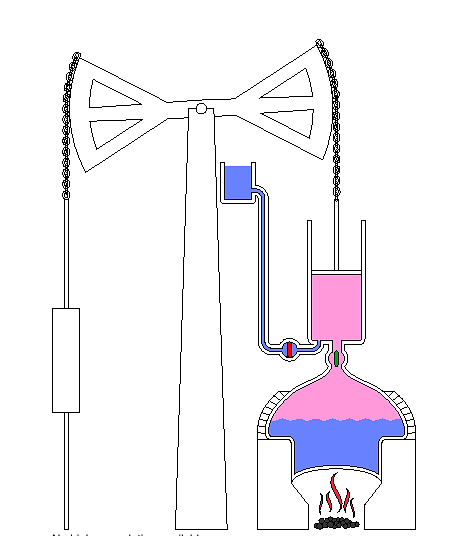

The principle of the steam engine was that heated water produces steam, which is 1500 times more voluminous. The steam, when it cools and condenses back to water, then dramatically reduces in volume and creates a partial vacuum. The vacuum creates a power of suction, which can be used to suck in water. In scientific terms, it was discovered in the 17th century by such scientists as Galileo (1564-1642) that the weight of the outside atmosphere (atmospheric pressure), with its higher pressure than the vacuum in the machine, creates an energy force which can be used to move something from one place to another. Instead of water, a piston might be drawn into the vacuum to create a power stroke. The power stroke could then move a levered beam that provided lift. When the vacuum tank is emptied using valves to let out the steam, the beam falls back to its natural position thanks to gravity, and so the piston is pulled back out of the vacuum tank, ready to repeat the cycle. The engine needed two essentials: coal to heat the water and pure freshwater that did not damage the machine's internal workings.

Savery and Newcomen exploited these principles to create a working steam engine. Newcomen had improved the power of Savery's machine by injecting cold water to speed up the condensation process. He also replaced the piston rod with a chain, which was much less likely to jam. There was still much room for improvement, though. A better-made machine with closer-fitting parts would be able to withstand much more pressure and so provide more power. In the 1760s, John Smeaton doubled the steam engine's efficiency but this was still not enough. In 1769, James Watt, a Scottish instrument maker found the way forward, ironically, after he was asked to repair a Newcomen machine.

James Watt

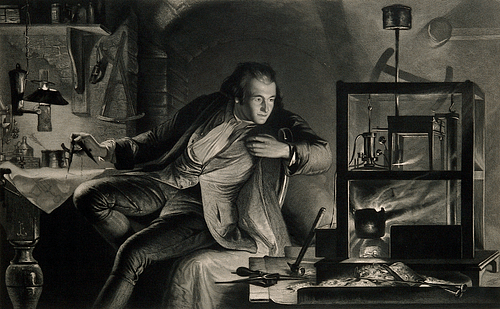

Watt was born in Greenock, Scotland in 1736. He trained in London and was employed by the University of Glasgow as the university's mathematical instrument maker when, in 1764, he was given a model of Newcomen's steam engine and asked by the university to repair it. In the course of his repairs, Watt realised there were several ways he could improve the design. Five more years of research and development followed, helped financially by John Roebuck, who took a two-thirds interest in the enterprise. In his autobiography (curiously written in the third person), Watt explains his motivation: "his mind ran upon making engines cheap as well as good" (Dugan, 54).

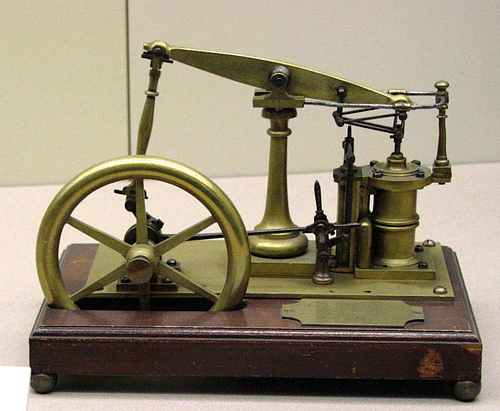

In 1769, Watt patented his new atmospheric engine. This innovative steam engine had a separate condenser to vastly increase efficiency. Watt separated the hot (piston cylinder) and cool (condenser) parts of the machinery, which were interfering with the efficiency of the condensing action since the piston cylinder was being unnecessarily cooled when water was injected to create the steam. His machine at this stage is, therefore, often called the separate condenser. Watt then continued to experiment, now working with Matthew Boulton, an industrialist from Birmingham who bought out Roebuck's interest in Watt's great enterprise after the latter had gone bankrupt. The pair started to make their engine a practical reality in 1775, working in the Soho Engineering Works in Birmingham. Watt knew that, in his own words, "the most likely line for the consumption of our engines is the application of them to mills which is certainly an extensive field" (Allen, 171)

Watt and Boulton continued to tweak their design over the next few years. A significant development was to increase the power by making sure steam pushed the piston down at the same time as the vacuum pulled it in. Steam was now introduced at both ends of the piston alternatively, depending on which direction the piston was moving. This is why this new type of engine is often called a double-acting engine. The development resulted in more power, a greater regularity in power, and a smoother delivery of that power. This power was further increased when Watt replaced the chain connecting the piston to the beam with a more rigid system of rods that allowed further push and pull on the piston.

Another refinement was to use better-fitting parts for the engine, minimising any loss of heat and energy. Watt sought the assistance of the expert cannon makers John and William Wilkinson to provide closer-fitting iron parts. The new components meant the machine had a much better seal between the piston and its casing. In addition, iron was much cheaper than brass, the previously favoured material. Further tweaks were adding a pump to remove condensed air and steam, adding insulation to the hot piston to help it stay hot and immersing the condensing tank in another tank of water to help keep it cool.

Sales of the Watt & Boulton Engine

The power of steam engines was now measured using a scale equivalent to the power of a horse. The term 'horsepower' was coined by Watt, and it helped assess the improvements made in future engines. Watt's final key development (which had already been used by rival inventors) was to convert the power of the engine not to a vertical chain or rods but to a rotary motion using a heavy flywheel connected by sun and planet gears. This arrangement made the action of the machine much smoother and less prone to wear and tear. Now the rotative steam engine could be used for just about any task where pulling, pushing, turning, lifting, and pressing were required. The culmination of this research and development came in 1784 with the engine that Watt and Boulton made for Samuel Whitbread (1720-1796). Whitbread ran a brewery in London, and the engine, installed in 1785 and in operation until 1887, was so successful that it helped him become Britain's most important brewer. The engine is today the oldest surviving rotative Watt steam engine and is on display in the Powerhouse Museum, Sydney.

Watt and Boulton were confident in their product, and again in 1784, they bought the Albion Mill in London, which was the first large factory entirely powered by steam. Manufacturers were invited to the mill to see the impressive Watt and Boulton engines working and then make an order. The strategy worked, and the next year a cotton mill owned by George and John Robinson in Nottingham became the first to have a James Watt & Co. engine.

Crucially for its commercial success, Watt's steam engine used only around one-quarter of the fuel Newcomen's engine needed. This made the engine's operation affordable to more businesses and meant it could be used in remote areas where there was not a large supply of coal. This was the vital consideration at the time and compensated for the engine's modest power, around 15-16 horsepower per hour. As the historian J. Mokyr notes, the Scotsman's achievements mean that "Watt is comparable to, say, Pasteur in biology, Newton in physics, or Beethoven in music. Some individuals did matter" (Dugan, 54).

A Gallery of 30 Industrial Revolution Inventions

Further Developments

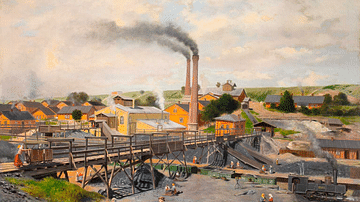

By 1800, Britain boasted over 2,500 steam engines (France, Britain's nearest competitor, had less than 200, while at the same time, the number in the USA was in single figures). Most of the British engines were used in mines, cotton mills, and manufacturing factories. Almost 500 of these engines were made by Watt and Boulton. 52 of Watt's engines were used in mines, 84 were used in cotton mills, and the rest in a wide range of industries. Even factories using traditional waterwheels started to use the Watt engine as a backup for when the local water levels were too low to be efficient.

It was also in 1800 that Watt retired, his patent now expired. The machine would long outlive its inventor, and it continued to improve thanks to new ideas from younger engineers. Indeed, Watt's patent had been holding some other inventors back, and these were now free to pursue further improvements. Watt was recognised for his contribution to science and engineering by having an electrical unit of measurement named after him.

Steam engines kept on evolving, and they benefitted from ever-better tool machinery that could make stronger and better-fitting parts. In the 19th century, steam engines were used for heavy machinery in factories, threshing machines in agriculture, printing presses, and sewage works across Britain and elsewhere. They revolutionised industry. For example, by 1835, around 75% of cotton mills in Britain were using steam power. Even where traditional handwork continued, such as in agriculture, the tools workers used were often made using steam-powered machines. The early engines had the advantage of being fuel-efficient and mobile, which made them a saleable product, but now, with much greater power as well, they could not only replace other sources of power like waterwheels but be used for entirely new purposes like transportation. Railways transformed Britain as steam-powered locomotives connected every part of the country.

The railways were made possible by the development of the expansion engine, which shut off the heat source before the steam had fully expanded, allowing the expansion to continue naturally and thus save fuel. Controlling the steam expansion using valves was another step forward. With constant tinkering by engineers actually using engines themselves and observing their peculiarities, the steam part of the process became so efficient that the condensing part became irrelevant.

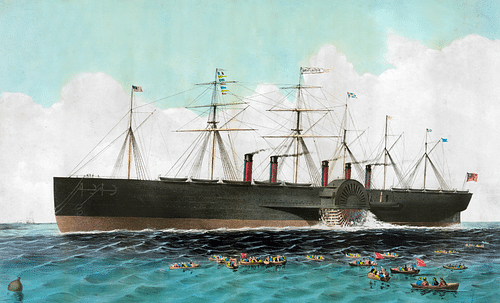

Some steam engines were now gigantic. James Watt died in 1819, but his company kept on going. James Watt & Co. provided the engines for the giant steamship SS Great Eastern, designed by Isambard Kingdom Brunel (1806-1859). Each of the two engines weighed 90 tons, and they were the biggest ever built up to that point. They had massive cylinders which measured 1.88 metres (6 ft 2 in) in length. The engines gave a total of 3,150 horsepower, which was double the power of any existing ship. The Great Eastern made its successful voyage to New York in 1860. Watt would have been mightily impressed.

Steam engines had by now been adopted across Europe, and they would remain the dominant power source until the 20th century when the combustion engine and electricity took over.

Impact of the Steam Engine

Steam engines brought success for inventors like Watt, and they brought great profits to manufacturers and other business owners as the costs of labour were reduced and economies of scale were achieved in production. Other benefits were seen in agriculture, where mobile steam engines became extremely useful at harvest time or for such large projects as draining fields. Steam power allowed the new railways to connect people as never before, and faster transportation made consumer goods cheaper. The coal and steel industries boomed to feed the steam engines and provide the raw material for the things they made. There were, too, many less positive effects. Skilled textile workers lost their jobs to power looms, as did those who ran stagecoaches, coaching inns, and stables as the trains took over from traditional transport methods. Urbanisation accelerated, and towns and cities became crowded and polluted places to live. Mechanised factories were noisy and often dangerous places to work. But there was no going back. Machine power, of whatever source, became so indispensable it is today nigh on impossible for us to imagine what life was like before the great steam revolution.