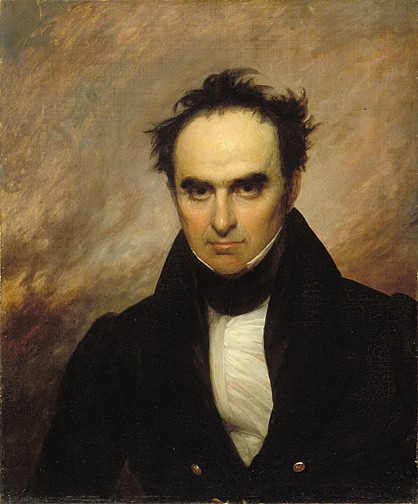

The Webster-Hayne debate was a series of back-and-forth speeches between Senator Daniel Webster of Massachusetts and Senator Robert Y. Hayne of South Carolina in January 1830. What started as a debate over the sale of western lands blossomed into an argument over the nature of the American Union itself, anticipating the Nullification Crisis and, indeed, the American Civil War.

Background: Sectional Rivalries

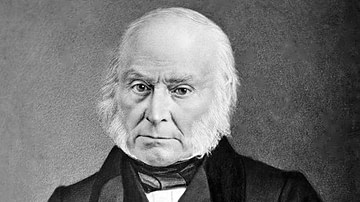

By the close of the 1820s, the United States had become increasingly divided along sectional lines. The American South, a largely agrarian society driven by slave labor, often found itself at odds with the industrializing North; gone were the days of political calmness and stability that had marked the 'Era of Good Feelings' (c. 1815-1825), with debates like the one surrounding the Missouri Compromise drawing the line between the 'free' states of the North and the 'slave' states of the South. In late 1828, the main point of contention was the implementation of the Tarriff of 1828 – better known as the 'Tarriff of Abominations' – that had been signed by John Quincy Adams in the waning months of his presidency. This was a protective tariff designed to help bolster Northern industries by placing fresh duties on European competitors. These European nations placed retaliatory tariffs on several American goods, including cotton, the staple crop of the South. Many Southerners, therefore, saw this tariff as helping Northern industrialists while suffocating their own economy. Because of the tariff, Adams quickly became the most hated man in the South, contributing to his 1828 election loss to Andrew Jackson.

One of the leading opponents of the tariff was John C. Calhoun, who had served as Adams' vice president and was now set to hold that same office under Jackson. Although he had been a staunch nationalist earlier in his career, Calhoun had since made a sharp heel turn to become a fierce advocate for states' rights. One of these rights, he argued, was that of nullification, which referred to the ability of a state to 'nullify' a federal law it believed to be unjust, until such a time as that law became enshrined in the Constitution. In his 35,000-word, anonymously written pamphlet on the topic of the 'Tarriff of Abominations', Calhoun stated that the tariff was "unconstitutional, unequal, and oppressive; calculated to corrupt the public morals and to destroy the liberty of the country" (quoted in nps.org). His answer, of course, was nullification; states, like his native South Carolina, should be able to hold conventions, in which they could vote to nullify federal acts such as this tariff. The idea was foreboding to many Unionists (like Jackson himself) who feared nullification to be the first step toward secession and, ultimately, the collapse of the Union. In December 1829, as Congress convened for the first time since Jackson's inauguration, the question laid heavy on their minds and would soon lead to one of the most dramatic and eloquent series of debates the Senate had yet witnessed.

The Question of the West

The debate was triggered on 29 December 1829, when Senator Samuel Foot of Connecticut rose to introduce a resolution on the Senate floor. At the time, American settlers were rapidly moving westward, with the federal government encouraging their migration by selling off public Western lands for cheap prices. But by now, the US government had more land on the market than could readily be sold; indeed, historian David Walker Howe writes that "the Native Americans were displaced faster than their lands could be sold" (368), with Georgia going so far as to raffle off some of the lands it had seized from the Cherokee in a lottery. To New Englanders like Senator Foot, this push toward westward expansion was not only unnecessary, but it was also hurting the development of the East. Property values in the New England and Chesapeake regions were depreciating as more people packed up and moved west, leaving fewer laborers to help build Eastern industry and infrastructure. Foot's resolution, therefore, was to limit the sale of Western lands until most of what was already on the market had been sold off. This would encourage Americans to stay in Eastern cities and towns and help improve industry there. Foot and the New Englanders believed that this would be beneficial to all, as the growth of Eastern cities would naturally provide better markets for the Western farmers.

But the Westerners did not see it this way – they believed that Foot's resolution sought to weaken the West by restricting the mobility of would-be settlers, who would instead be used as cheap labor by the greedy New England manufacturers. On 18 January 1830, Senator Thomas Hart Benton of Missouri rose to oppose Foot's resolution, accusing the New Englanders of trying to "check the growth and to injure the prosperity of the West" as well as wanting to keep "the vast and magnificent valley of the Mississippi for the haunts of beasts and savages" (quoted in Howe, 368). Benton, understanding the growing rivalry between North and South, ended his speech by calling upon the South to come to the aid of the West. His appeal would be answered by Senator Robert Y. Hayne of South Carolina, an up-and-coming politician and protégé of Vice President Calhoun. Handsome and well-educated, Hayne rose on 19 January to defend Benton’s position and to advocate that the Western lands be turned over to the states to hand out to settlers as they pleased.

Hayne vs. Webster

Hayne, however, was not content with merely defending the sale of Western lands; the question of sectional differences having already been broached, he was prepared to widen the argument to include an issue much dearer to his heart – that of the hated tariff and his state's right to nullify it. Speaking on the tariff, Hayne said, "the fruits of our labor are drawn from us to enrich other and more favored sections of the Union…the rank grass grows in our streets; our very fields are scathed by the hand of injustice and oppression" (quoted in Meacham, 127). The solution to this oppression, according to Hayne, was for greater local, rather than central, authority. He continued:

Sir, I am one of those who believe that the very life of our system is the independence of the states, and that there is no evil more to be deprecated than the consolidation of this Government. It is only by a strict adherence to the limitations imposed by the constitution on the Federal Government that this system works well, and can answer the great ends for which it was instituted.

(ibid)

In his speech, Hayne had certainly broadened the topic to include most of the important issues of the day but, in doing so, had brought the nature of the American Union into question. This was something that Senator Daniel Webster of Massachusetts, watching Hayne speak in the Senate chamber, could not abide. Feeling inclined to defend New England and, indeed, the Union itself, Webster stood on the day following Hayne’s speech, declaring, "I rise to defend the East!" (quoted in Howe, 369). A nationalist and proponent of industry and protective tariffs, Webster began his own speech by affirming that New England had always been a friend of the West. He reminded his colleagues that it had been a New Englander who had drafted the Northwest Ordinance of 1787, which had first opened the West to settlement. He argued that the protective tariffs currently bolstering industry in New England were also serving the mutual interests of the West and the so-called 'American System', as the policy for interstate internal improvements was known, benefitted the entire nation.

Having sought to smooth over the rift between Northeast and West, Webster now turned his attention toward Senator Hayne and the South. He brought up that, in reaction to the tariff, Hayne, Calhoun, and their friends in the South Carolina state legislature wished to resort to nullification. Decrying this as a threat to the existence of the Union, Webster said:

They [i.e. South Carolina] significantly declare that it is time to calculate the value of the Union; and their aim seems to be to enumerate, and to magnify, all the evils, real and imagined, which the Government under the Union produces. The tendency of all these ideas and sentiments is obviously to bring the Union into discussion as a mere question of present and temporary expediency; nothing more than a mere matter of profit and loss.

(quoted in Meacham, 128)

Webster ended his first reply to Hayne by proclaiming that "I am a Unionist…I would strengthen the ties that hold us together. Far, indeed, in my wishes, very far distant be the day, when our associated and fraternal stripes shall be severed asunder" (ibid). With this, Webster implicitly dared Hayne to directly challenge what he had been dancing around in his first speech with respect to the American Union. Five days later, Hayne took the bait. Defending every supposed 'right' of the Southern states, from slavery to nullification, Hayne said that the Northern Yankee "has invaded the State of South Carolina, is making war upon her citizens, and endeavoring to overthrow her principles and institutions" (quoted in Howe, 370). He went on to condemn the "false philanthropy" of both abolitionists and those who opposed Indian removal and doubled down on South Carolina’s need to nullify the tariff. It was Hayne’s voice but distinctly Vice President Calhoun's words; indeed, Calhoun, from his seat presiding over the Senate chamber, could be seen passing notes down to his younger protégé during the speech.

Webster's Second Reply to Hayne

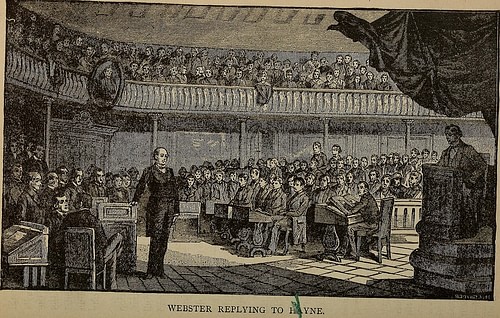

But little did Hayne know that he had played directly into Webster's hands. The Massachusetts senator had longed for a chance to defend the Union before a large audience. Now, having successfully escalated the argument from a minor debate over the sale of Western lands into a debate over the nature of the country itself, he had his chance. On the cold day of 27 January 1830, Senator Webster stood once again, dressed in a blue American Revolutionary War era coat and white cravat, to deliver his second reply to Hayne, a speech that would be quoted by American schoolchildren for the next century. Laying out his Unionist doctrine, Webster asserted that the Constitution had not been drafted by the states, but by the American people, who had carefully distributed sovereign powers between the federal and state governments. The states, therefore, had no right to decide to limit federal authority through acts like nullification. Near the close of his speech, Webster delivered his dramatic defense of union:

I have not allowed myself, sir, to look beyond the Union, to see what might lie hidden in the dark recess behind. I have not cooly weighed the chances of preserving liberty when the bonds that unite us together shall be broken asunder. I have not accustomed myself to hang over the precipice of disunion, to see whether, with my short sight, I can fathom the depth of the abyss below; nor could I regard him as a safe counsellor in the affairs of this government, whose thoughts should be mainly bent on considering, not how the Union may be best preserved, but how tolerable might be the condition of the people when it should be broken up and destroyed. While the Union lasts, we have high, exciting, gratifying prospects spread out before us, for us and our children. Beyond that I seek not to penetrate the veil. God grant that, in my day, at least, the curtain may not rise! God grant that on my vision never may be opened what lies behind! When my eyes shall be turned to behold for the last time the sun in Heaven, may I not see him shining on the broken and dishonored fragments of a once glorious Union; on States dissevered, discordant, belligerent; on a land rent with civil feuds, or drenched, it may be, in fraternal blood! Let their last feeble and lingering glance rather behold the gorgeous ensign of the republic, now known and honored throughout the earth, still full high advanced, its arms and trophies streaming in their original luster, not a stripe erased or polluted, nor a single star obscured – bearing for its motto, no such miserable interrogatory as 'what is all this worth?' nor those other words of delusion and folly, 'Liberty first and Union afterwards'; but everywhere, spread all over in characters of living light, blazing on all its ample folds, as they float over the sea and over the land, and in every wind under the whole Heavens, that other sentiment, dear to every true American heart – Liberty and Union, now and forever, one and inseparable!

Webster's speech was followed by a hushed silence; one historian wrote that the senators "did not applaud; they did not shout their appreciation. They just sat as if in a trance, all motion paralyzed" (Robert Remini, quoted by nps.org). The speech was soon picked up by newspapers, and Webster's Second Reply to Hayne was soon read more than any previous speech in US history. Webster had won the debate and, in the eyes of many Americans, convinced them of his main point – the American Union must be preserved. Three decades later, Abraham Lincoln, during his own struggle to preserve the Union, would resonate with Webster's speech, which he called "the very best speech that was ever delivered" (quoted in Howe, 372).

Aftermath

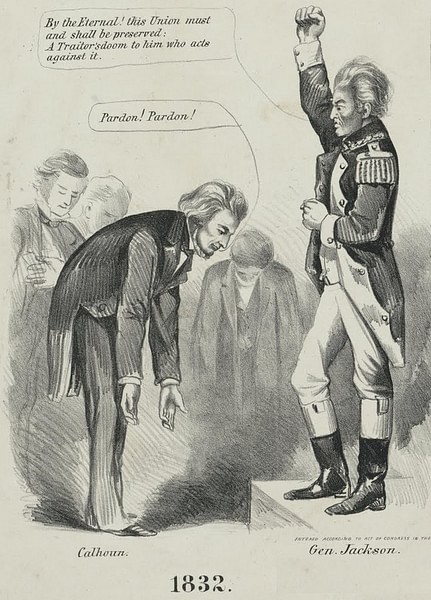

Aside from the dramatics of Webster's final speech, the debate fizzled out anticlimactically. Ultimately, Senator Foot's resolution – which had ignited the fire keg in the first place – was shelved, but neither did Congress approve Senator Benton's plan of lowering the prices of Western lands even further. With the question of the Union now having been articulated, many Americans wondered where President Jackson stood on the issue – would he identify with his fellow slave-holding Southerners, or would he find common ground with the Unionists? The answer would come a few months after the debate, at a dinner party held at the White House to celebrate the birthday of Thomas Jefferson. After a long-winded speech given by Robert Hayne, in which he predictably praised Jefferson's states' rights beliefs, Jackson stood up and offered his own toast: "To our Federal Union". As he spoke those words, the president stared directly into the eyes of Vice President Calhoun, who then stood and responded, "The Union. Next to our liberty, the most dear. May we always remember that it can only be preserved by respecting the rights of the states and by distributing equally the benefits and the burdens of the Union" (quoted in Howe, 373).

The stage was set for the showdown between Jackson's government and South Carolina in the Nullification Crisis (1832-33), the first major battle between federal authority and states' rights before the American Civil War. Although Jackson could be swayed to support states' rights if it was in his interest to do so – such as when he allowed Georgia to ignore a Supreme Court ruling in order to take Cherokee land – he was generally intent on preserving the Union and expanding the power of his own office, goals that South Carolina stood in the way of with its insistence on nullification. The questions articulated in the Webster-Hayne Debate would, of course, extend far beyond the Jacksonian era and would become increasingly relevant as sectional issues deepened and the country found itself hurtling toward civil war.