The Whiskey Rebellion was a violent uprising that occurred in western Pennsylvania in 1794, in opposition to an excise tax on liquor. After anti-tax protestors assaulted federal tax collectors and threatened to march on Pittsburgh, President George Washington (served 1789-1797) raised a federalized militia that swiftly suppressed the insurrection. The incident strengthened the authority of the United States federal government.

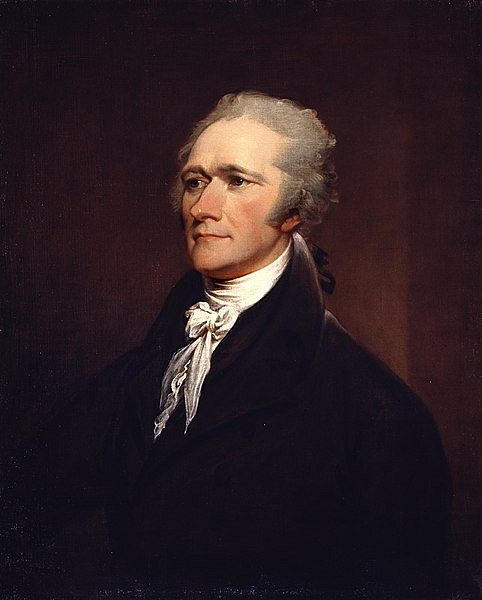

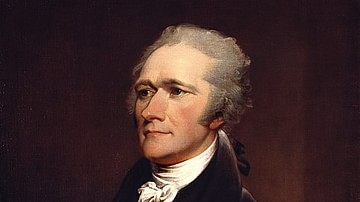

Alexander Hamilton had proposed an excise on distilled spirits to fund his ambitious economic program, which was enacted by Congress in 1791. This so-called 'Whiskey Act' proved unpopular, particularly among the small farmers living on the western frontiers of the United States. Liquor was an important commodity in the West, where many farmers operated small stills and used liquor as an informal currency; the new excise tax was something that many of them could not afford. Protests broke out in 1792 and 1793, with much of the rhetoric accusing Hamilton and his nationalist Federalist Party of being aristocrats who sought to use the tax to subjugate the small western farmers and deprive them of their liberties. The Federalists, for their part, accused the protestors of fomenting anarchy and urged President Washington to take decisive action.

The anti-tax protests escalated in the summer of 1794 when protestors attacked the home of a federal tax collector before demonstrating on Braddock's Field outside Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, where they talked of attacking the federal garrison in the city. Washington finally yielded to his Federalist advisors and called up a federalized militia to suppress the rebellion. Led by Hamilton and Virginia governor 'Light-Horse' Henry Lee III, the 12,950-man militia army marched through western Pennsylvania in October 1794, with all opposition melting before it. This show of military force ended the Whiskey Rebellion and proved that under the new Constitution, the federal government was strong enough to enforce adherence to its laws. However, the government's aggressive response unnerved many Anti-Federalists, who feared the growing authority of the national government. This controversy contributed to the rise of the Democratic-Republican Party in opposition to the Federalists, ushering in the birth of political partisanship in the United States.

The Whiskey Act

In the aftermath of the American Revolution (1765-1789), the fledgling United States was saddled with a mountain of debt. The national government owed $54 million in debt, while the states collectively owed an additional $24 million – such had been the "price of liberty", as Alexander Hamilton, Secretary of the Treasury for the Washington administration, remarked in the opening pages of his Report on Public Credit (Chernow, 297). While other men may have balked in the face of such an overwhelming amount of debt, Hamilton smelled opportunity. In his report, submitted to Congress in January 1790, he recommended consolidating national and state debt into a single sum to be paid off by the federal government; this would have the dual effect of establishing public credit while increasing the legitimacy of the federal government. Although the plan sparked fierce debate and was hotly opposed by Anti-Federalists, it was nevertheless approved by Congress in the summer of 1790.

It was now left for Hamilton to figure out exactly how the federal government was supposed to start paying off such an exorbitant sum. The existing duties on foreign imports, which at the time made up the primary source of income for the federal government, were already as high as Hamilton dared raise them but were still insufficient to fund his ambitious financial program. The only feasible solution was to implement some kind of excise tax on domestically manufactured goods. Although the new United States Constitution granted Congress the power to levy excise taxes, it was abundantly clear that such a move would be unpopular; so soon after the Revolution, many Americans still associated direct taxation with tyranny. Still, Hamilton sorely needed the revenue an excise tax would bring. He believed that a tax on distilled spirits would be less objectionable to the public than a similar tax on other goods; to sway the public to his side, he framed it as a 'sin tax' that would reduce Americans' consumption of hard liquors and had physicians speak out on the harmful effects of alcohol. Despite the skepticism in Congress over Hamilton's so-called 'Whiskey Act', the bill was passed in March 1791.

Hamilton had known that the Whiskey Act would be controversial, but he had not anticipated just how outraged many Americans would be, particularly among the settlers along the country's western frontier. The land to the west of the Appalachian Mountains was still sparsely settled by white settlers; indeed, the largest western settlements still had only a few hundred permanent residents, and the few roads that existed were poorly maintained. As a result, small western farmers, who made a living growing crops like corn, rye, and grain, had difficulty bringing their produce to market. Oftentimes, their goods would spoil before they could get to a settlement large enough to find buyers. To combat this, many farmers distilled their grain into liquor, which was much easier to transport and preserve. The practice became so widespread that by the 1790s, most western farmers operated small stills, and liquor was often used as an informal currency.

The Whiskey Act, therefore, was widely viewed as an attack on the livelihoods of western farmers, many of whom could not afford to pay the tax. Critics likened the tax to the hated Stamp Act of 1765, which had been one of the catalysts for the American Revolution. One pamphleteer accused Hamilton and his Federalist followers of "wishing to imitate the corrupt principles of the court of Great Britain" by introducing such an excise tax (quoted in Chernow, 469). Many saw the Whiskey Act as an attempt by the central government to extend its tendrils of power into the West and force the frontiersmen to feel the authority of Congress. Protestors began to accuse the federal government of being run by "aristocrats" and "moneyed men" who sought to deprive them of their liberties (Wood, 136). This kind of rhetoric brewed fear, which in turn led to instances of violence; as had happened to the British stamp distributors three decades before, federal tax collectors became the targets of unruly mobs, which threatened to beat, whip, or tar and feather them. In August 1792, Colonel John Neville, the federal tax collector in Pennsylvania, was accosted by one such mob which promised to "scalp him, tar and feather him, and finally reduce his house and property to ashes" should he go ahead and collect the whiskey tax (Chernow, 469).

Escalation

By 1792, protests had spread to the western frontiers of every state south of New York. Despite the threats against tax collectors, most of the protests were, as of yet, peaceful – petitions were sent to Congress asking for the repeal of the Whiskey Act, while assemblies of prominent citizens gathered to formally condemn the tax. At one such assembly in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, the Swiss-born Anti-Federalist Albert Gallatin helped draft a resolution that stated that protestors would continue to obstruct the collection of the excise tax until its total repeal, and that officials who insisted on collecting the tax would be treated with "the contempt they deserve" (Chernow, 469). Hamilton and the Federalists, however, were not about to suffer the indignation of having their authority flouted by frontier farmers and urged President George Washington to take "vigorous and decisive measures" against the protestors, whom they accused of fomenting anarchy (ibid). Although Washington was unwilling to take such an uncompromising stance, he did issue a statement in September 1792 in which he condemned the resistance to federal authority and promised that the whiskey tax would be enforced.

Opposition to the Whiskey Act continued to grow in 1793, especially in western Pennsylvania. In June, the residents of Washington County burned an effigy of John Neville, and on 22 November, a group of men broke into the home of tax collector Benjamin Wells and forced him to resign his office at gunpoint. But despite these instances of violence, the federal government was still reluctant to retaliate; it was not until February 1794 that President Washington released another statement expressing his determination to uphold law and order in the West. In May 1794, the Pennsylvania state government finally acted, issuing subpoenas for sixty distillers who had not yet paid the excise tax. Federal Marshal David Lenox was sent to deliver the writs and was joined in this duty by the much-hated Colonel Neville. Far from quelling the protests, this would only make things worse.

Rebellion

On 16 July 1794, John Neville awoke to find that thirty armed protestors had surrounded his home of Bower Hill. The protestors demanded that Neville turn over Marshal Lenox, who they believed was in his house; in reality, Lenox had gone to Pittsburgh the evening before. When Neville could not produce the marshal, the protestors turned rowdy, prompting the tax collector to fire a gunshot at them. The shot hit a man named Oliver Miller, who was mortally wounded. The enraged rebels fired back, and it was only through the help of his slaves that Neville prevented them from storming into his home. After they had left, Neville called for help and was joined by Marshal Lenox himself and ten US soldiers who had come to defend his property. The next day, over 500 armed rebels returned to surround Neville's home. They were led by Major James McFarlane, a veteran of the American Revolutionary War. For nearly an hour, a firefight raged between the rebels and the soldiers until some eyewitnesses believed they had spotted a white flag waving from the house.

McFarlane ordered a ceasefire and stepped into the open to see what Neville wanted. At that moment, he was shot dead by someone within the house. The rebels, believing they had been tricked, resumed the attack, eventually setting fire to the house. Most of the occupants of the house fled at this point, except for Lenox and Neville's son Presley, who were captured by the rebels; they did not remain hostages for long, however, and soon made their escape. The death of Major McFarlane further radicalized the west Pennsylvanian countryside. On 1 August, close to 7,000 demonstrators arrived at Braddock's Field, just outside Pittsburgh. Mock guillotines were erected in the field, a clear allusion to the Reign of Terror that was currently engulfing Revolutionary France. One rebel leader, David Bradford, went so far as to idolize Maximilien Robespierre and call for an American Committee of Public Safety to be established to mete out Jacobin-style justice to the aristocratic Federalists. There was even serious talk of attacking the federal garrison in Pittsburgh to obtain weapons, with Bradford promising that the rebels would "defeat the first army that comes over the mountains and take their arms and baggage" (Chernow, 470).

The nature of this insurrection unnerved the Federalists; the temporary national capital of Philadelphia was, after all, not so far away from the trouble in the western part of the state. Moreover, the rebels' praise of the French Revolution – which had plunged Europe into total war and devastation – was more than a little alarming, causing the Federalists to consider the rebels an existential threat to their young republic. Secretary of War Henry Knox called for the marshaling of a "superabundant force" to meet the rebels, while Hamilton wrote that the government "ought to appear like Hercules" and overawe the rebels into submission with a "display of strength" (Chernow, 471). To drum up support for military action, Hamilton submitted essays to Philadelphia newspapers. Writing under the pen name 'Tully', he accused the rebels of plotting to tear down the Constitution and sink the nation into anarchy.

Suppression

Despite the clamor from the Federalists, Washington still clung to the hope that military intervention would not be necessary. In early August 1794, he sent three commissioners to Pittsburgh to sound out the situation there; the commissioners reported back that extremists were determined to resist the tax "at all hazards" and that military force may indeed be necessary to enforce the law. Washington then convened an eight-hour-long cabinet meeting in which it was decided – over the protestations of Secretary of State Edmund Randolph – that a federal militia would be raised, to be called from the states of New Jersey, Maryland, Virginia, and Pennsylvania. To demonstrate the might of the federal government, 12,950 men were to be raised; this was a larger army than the Continental Army had been for most of the Revolutionary War. Few men volunteered willingly, leading the government to implement a draft.

In early September, riots broke out to protest the raising of the militia force. 150 people were arrested during an anti-draft protest in Hagerstown, Maryland, while three other anti-draft riots were crushed in Virginia. On 11 September, protestors raised a liberty pole in Carlisle, Pennsylvania, where the militia army was mustering. When the undisciplined militia soldiers went to arrest the protestors, scuffles broke out that led to the deaths of two civilians. Washington saw to it that the two soldiers responsible for the deaths were arrested and tried by civilian, rather than military, courts. On 30 September 1794, President Washington arrived at Carlisle, with Hamilton at his side, to inspect the gathering army; this remains the only time a sitting US president has taken command of an army in the field. Washington was met by Pennsylvania Congressman William Findley, who claimed that military force was unnecessary and pleaded with the president to send the army away. Washington told Findley that he would not desist but promised not to harm the Pennsylvanians so long as no shots were fired at his army. Hamilton, on the other hand, was less accommodating; when Findley mentioned the name of a rebel leader, Hamilton promised that the man would be "skewered, shot, or hung from the first tree" (Chernow, 475).

On 9 October, Washington traveled to Fort Cumberland, Maryland, to inspect the southern wing of the army. Satisfied that the army would not meet much resistance, he returned to Philadelphia, turning over the command to 'Light-Horse' Henry Lee III, the governor of Virginia. Hamilton remained with the army to act as a civilian advisor while Daniel Morgan, a hero of the American Revolution, was promoted to major general and given command over part of the army. In October 1794, the federalized militia began its march into western Pennsylvania. It met no resistance, and over 2,000 rebels scattered into the hills to escape the wrath of the federal government, much to Hamilton's disappointment. In the end, only 24 men were arrested and charged with treason. Two were convicted but were ultimately pardoned by President Washington. The Whiskey Rebellion, which had caused so much dread and alarm, was over without so much as a single battle.

Aftermath & Significance

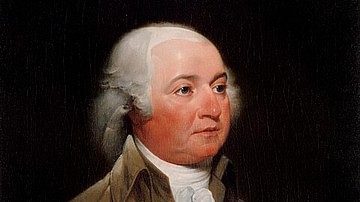

The near bloodless suppression of the Whiskey Rebellion was seen as a great victory for the Washington administration and the Federalist Party. For the Federalists, it had been the first successful test of national authority under the new Constitution and had shown that the federal government was strong enough to compel obedience to its laws. Many Anti-Federalists, however, were unnerved by the heavy-handed response of the Washington administration and condemned the use of military force. Thomas Jefferson, an outspoken opponent of Hamilton's Federalist agenda, quipped that "an insurrection was announced and proclaimed, and armed against, and marched against, but could never be found" (Quoted in Wood, 138). Controversy over the government's aggressive response to the Whiskey Rebellion – combined with controversy over the Jay Treaty later that same year – gave rise to a new political faction, the Democratic-Republican Party, to oppose the Federalists. Political partisanship had emerged in the United States.

As for the Whiskey Act, it remained in force following the quelling of the insurrection. Although it sparked no further riots, federal tax collectors often had difficulty enforcing the act, as many western distillers continued to successfully evade it. In 1801, Thomas Jefferson was sworn in as president and the Democratic-Republicans gained control of Congress. The following year, they repealed the Whiskey Act as well as several other taxes that had been put in place by the Federalists.