William Dampier (1651-1715) was an English explorer, navigator, and naturalist, who was the first person to circumnavigate the world three times. He was also among the first Englishmen to step foot on Australian soil when he sailed into King Sound (near present-day Broome, Western Australia) on the Cygnet in 1688.

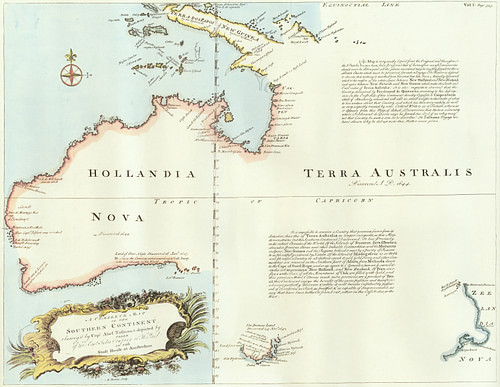

This part of the Australian mainland was then known as New Holland, the name the Dutch explorer, Abel Janszoon Tasman (1603-1659), had given to the western and northern parts of Australia in 1644. Dampier was keen to explore the uncharted eastern coast and map the coastline of the fabled 'Terra Australis Incognita' – the vast southern landmass – the existence of which had been posited by Aristotle (l. 384-322 BCE), who reasoned that continental land in the northern hemisphere would be balanced by land in the southern hemisphere.

A series of events, ranging from violent storms to the sinking of the HMS Roebuck, a British Royal Navy vessel Dampier commanded, ultimately prevented him from circumnavigating the southern continent. Had he done so and struck land on the eastern coast, he would now be recognised for the European discovery of Australia, more than half a century before Captain James Cook (1728-1779) sailed into Botany Bay in 1770, claiming it for the British crown as a colonial outpost and calling it New South Wales to counter the Dutch name of New Holland.

William Dampier has been in danger of being relegated to a footnote in history – sandwiched between Sir Francis Drake's (c. 1540-1596) defeat of the Spanish Armada in 1588 and eclipsed by Cook's celebrated voyages.

Dampier should be remembered as Australia's first naturalist and the first European to undertake a scientific study of Australian flora and fauna. His published travel accounts also introduced into the English language the words avocado, flamingo, cashew, chopstick, catamaran, barbecue, and breadfruit. As a contributor to scientific inquiry, he influenced Captain James Cook, Charles Darwin (1809–1882), Sir Joseph Banks (1743-1820), and Dampier inspired the writing of Daniel Defoe (d. 1731) and Jonathon Swift (1667-1745). Above all, Dampier was perhaps the finest seafarer and navigator of his time.

Early Life of a Buccaneer

William Dampier was born in 1651 in East Coker, Somerset, England, the second son of a tenant farmer, George Dampier and his wife, Anne, who both died when Dampier was a young boy. He started his seafaring life when his guardians arranged for him to be indentured to a ship's captain in Weymouth, setting off on a 4000 nautical mile (7408 km) voyage to Newfoundland. He did not enjoy the frigid waters and cold weather, so he headed to London on his return and found passage in 1670 on the East Indiaman, John and Martha, bound for Bantam in Java. On this voyage, Dampier gained experience in navigation, particularly the calculation of longitude and observation of wind and weather patterns.

The John and Martha returned to London after two months in Bantam, and Dampier enlisted in the Royal Navy in 1672. He was posted to HBMS Royal Prince and took part in the Battles of Schooneveld, two fierce maritime encounters during the Third Anglo-Dutch War (1672-1674). After falling ill, Dampier accepted an offer to manage a sugar plantation (Bybrook) in Jamaica in 1674. It was a fateful decision because it led to Dampier's buccaneering life on the high seas.

Dampier and his employer, William Whalley (d. 1676), clashed over the management of the plantation, and Dampier soon left Bybrook, trying his luck with logging in the Bay of Campeche, at the southern end of the Gulf of Mexico. The purple-red dye from logwood trees commanded a high price in London, but by 1676, Dampier realised that any fortune to be made would not come easily since England and Spain were in conflict over control of the logging industry. His time as a logger, however, contributed to Dampier's impressive ability to describe nature. He kept meticulous journals throughout his life, starting with his ethnographic observations in the Bay of Campeche of monkeys, spiders, snakes, and the armadillo. Dampier's drawings and the introduction of the term 'subspecies' into the English language later influenced Darwin's theory of evolution.

Dampier left behind his logging life after a hurricane in the Bay of Campeche in June 1676. Dampier's detailed account of this hurricane has been recognised by scientists as the "first accurate description of this phenomenon" (Preston, 109).

Dampier soon fell in with a band of buccaneers (a term specific to the Caribbean and Pacific coast of Central America), and plundering became his source of income. When Dampier's travel journals were later published to critical acclaim, he would downplay his buccaneering career, preferring to reframe his account as one of scientific enquiry, which through unfortunate circumstances, had to be conducted in the company of drunken thieves and ruffians. Yet, the English viewed buccaneering as a low-cost way of countering the Spanish, who had laid claim to Jamaica before its capture in 1655 by the English. Buccaneers were often accepted into high-society – Sir Henry Morgan (c. 1635-1688), for example, a ruthless Welsh buccaneer was elevated to knighthood in 1674 by King Charles II of England (r. 1660-1685) and appointed Lieutenant-Governor of Jamaica.

Dampier spent the next twelve years on the high seas, sailing on various buccaneer ships, but all the while recording his observations of animals, plants, and the people he encountered. Aboard the Revenge in the Cape Verde Islands in 1683, he eloquently described the flamingo:

I saw a few flamingos, which is a sort of large fowl, much like a heron in shape, but bigger, and of a reddish colour. They delight to keep together in great companies, and feed in mud or ponds, or in such places where there is not much water... (A New Voyage Round the World, ch. 4.)

First Visit to New Holland

In 1687, Dampier joined the British privateer, the Cygnet, captained by Charles Swan (d. 1690) and spent three years onboard, crossing the Pacific. His role as navigator allowed him to chart winds and currents – maps and charts that were later consulted by Captain James Cook and contributed to the knowledge used to draw up 18th-century maps of trade winds in the Pacific region.

After a prolonged stay in Mindanao in the Philippines and a near mutiny against Swan, the Cygnet sailed towards the island of Timor with John Read as captain. Dampier recorded in his journals that the northern coast of New Holland, as drawn by the Dutch East India Company cartographers during Abel Tasman's explorations, was just 250 nautical miles (463 km) to the south. What had not yet been resolved was whether the charted coastline of New Holland belonged to one vast landmass or whether it consisted of many islands.

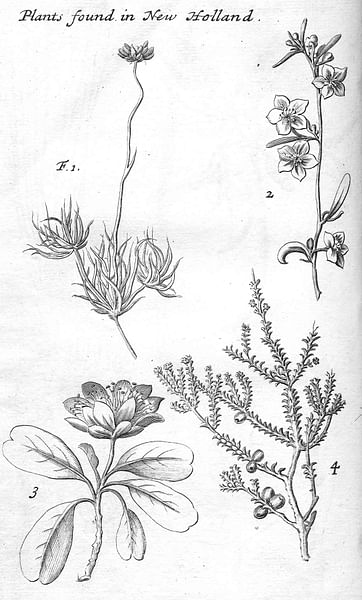

The Cygnet also needed to be careened to caulk and repair the hull, so in January 1688, the vessel arrived in King Sound. Dampier and the crew remained there for two months, repairing the Cygnet. Dampier collected plant specimens and kept his illustrations of Australian flora and fauna in water-tight bamboo tubes sealed with wax. One of the collected specimens was the wildflower, the Sturt Pea, the discovery of which has been given to inland explorer Charles Sturt (1795-1869), even though Dampier collected it over 150 years before Sturt.

Dampier established relations with indigenous Australians, most likely the Bardi, during his time in New Holland, but his views were less than favourable. In his 1697 book, A New Voyage Round the World, he wrote:

The inhabitants of this country are the miserablest people in the world. ... setting aside their human shape, they differ but little from brutes. ... They are long-visaged, and of a very unpleasing aspect, having no one graceful feature in their faces. (ch. 16.)

Dampier's description and attitude later influenced Sir Joseph Banks, who wrote in his Endeavour Journal:

... 5 people who appeared through our glasses to be enormously black, so far did the prejudices which we had built on Dampier's account influence us, that we fancied we could see their colour when we could scarce distinguish whether or not they are men. (1770 April 22)

Prince Jeoly & Travel Writing Fame

Dampier was tiring of the buccaneer lifestyle and returned to England in 1691 after finding himself marooned with two shipmates on the Nicobar Islands, following Dampier's desire to leave the Cygnet. He managed to sail a native proa (double-hulled boat) from the islands to Achin in Sumatra, where he stayed a year before taking the trading ship Curtana back to the London docks.

On the way home, William Dampier became a slave trader. He purchased a heavily tattooed man at Fort Saint George (India), known as the painted Prince Jeoly, who was originally from Miangas (present-day Palmas, North Sulawesi). Ever the journalist, Dampier described Prince Jeoly as being:

…painted all down his breast, between his shoulders behind: on his thighs (mostly) before; and in the form of several broad rings or bracelets round his arms and legs. (Mundle, 206).

Despite his buccaneering years at sea, Dampier had little to show in the way of profits, and he only had his journals and collected specimens. He sold Prince Jeoly (known as Prince Giolo in England) for a handsome sum, and he was put on public display as a curiosity. Jeoly died of smallpox a few months later while in Oxford, and his skin was preserved and hung at the anatomy school at Oxford University for hundreds of years.

Dampier spent the next few years writing his first book, A New Voyage Round the World, which was published in 1697 and based on his many journals, and he also became reacquainted with his wife, Judith, whom he had not seen for twelve years. His book was an immediate bestseller and is said to have influenced the English poet and literary critic, Samuel Taylor Coleridge's (1772-1834) poem, The Rime of the Ancient Mariner, and Jonathan Swift, whose fictional character in Gulliver's Travels, Captain Lemuel Gulliver, was said to be based on Dampier's experiences.

A New Voyage Round the World brought Dampier to the attention of the British Admiralty and the Royal Society, who invited him to give lectures on his adventures and his visit to New Holland. The government then requested he command the first scientific research expedition to New Holland.

Second Visit to New Holland

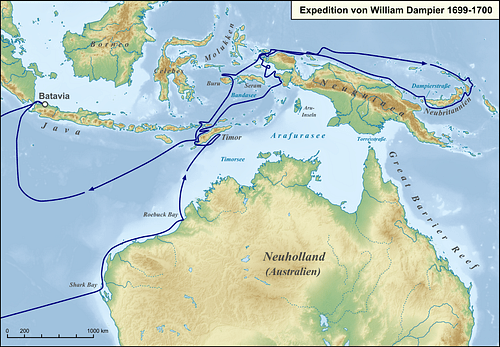

The expedition was trouble-plagued from the start. Dampier was assigned the HMBS Roebuck – a 96-foot (29 m), 26-gun former navy fireship that turned out to be unseaworthy. The Roebuck crossed the Indian Ocean and made landfall on the west coast of New Holland in August 1699 in a bay Dampier named Shark's Bay (near present-day Carnavon and now known as Shark Bay).

He sailed north along the western coast, mapping 869 miles (1,400 kilometres) of coastline between Shark's Bay and Lagrange Bay, south of Broome. Dampier collected 20 specimens of Australian plants, preserved in the British Museum, and kept detailed records of ethnographic observations.

Of the landscape, Dampier said:

The land by the sea for about 5 or 600 yards is a dry sandy soil, bearing only shrubs and bushes of divers sorts. Some of these had them at this time of the year, yellow flowers or blossoms, some blue, and some white; most of them of a very fragrant smell. (A Voyage to New Holland, ch. 3.).

Dampier also recorded the finding of a dugong (sea cow) in the stomach of a large shark caught in Shark's Bay. He described it as having the head and bones of a hippopotamus, with teeth up to eight inches long.

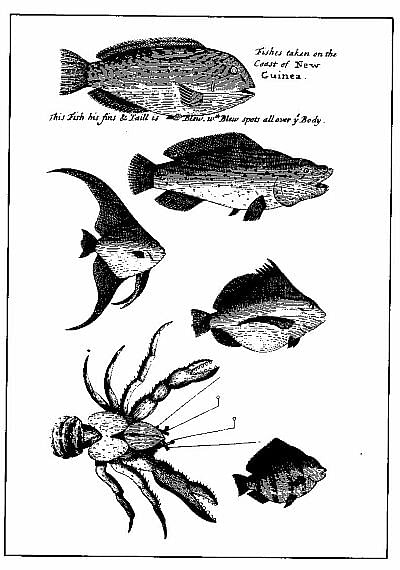

After two months exploring and searching unsuccessfully for water, Dampier left New Holland with an urgent need to replenish the Roebuck's water supplies, heading for Timor and charting the north coast of New Guinea along the way and proving that New Britain was a separate island.

Dampier's dreams of mapping the uncharted east coast of New Holland never came to fruition. The Roebuck was proving to be unseaworthy with its worm-eaten hull, and the vessel sank in Clarence Bay on the western Ascension Island coast after putting in for repairs in February 1701. Dampier managed to salvage his Shark's Bay botanical specimens, some shells, charts, and illustrations and returned to London in August 1701 to face an unexpected court-martial and an inquiry into the sinking of the Roebuck.

Lieutenant George Fisher

When Dampier took command of the Roebuck, his reputation as a buccaneer preceded him, resulting in conflict among the 50-person crew. Lieutenant George Fisher was appointed by the navy as the Roebuck’s second-in-command and stirred unrest by suggesting that Dampier would use the Roebuck to take up buccaneering activities again.

Before reaching Bahia (Brazil), Dampier had ordered Fisher to be caned for insubordination, fearing the lieutenant would lead a mutiny, and handed him over to the governor of Portuguese Brazil's then capital, Salvador, to await a ship that would return him to London.

By the time Dampier arrived back in London, Fisher had been preparing his case against him for two years, accusing Dampier of cruelty. The inquiry into Roebuck’s sinking – which saw Dampier cleared of responsibility – was conducted against a backdrop of disappointment that the east coast of New Holland remained a mystery. Dampier's court-martial was held aboard HMS Royal Sovereign in June 1702, and he was found guilty of cruelty, ordered to forfeit the salary he had received during his time commanding the Roebuck, and was declared unfit to command any of His Majesty's ships.

The remains of the Roebuck were discovered in 2001 by a team commissioned by the Western Australian Maritime Museum. The wreck contained some of Dampier's specimens, including a clamshell, and the ship's bronze bell.

A Buccaneer Once More

Despite the Roebuck’s sinking and Dampier's court-martial, the success of his published travel journals and the scientific value of the plant specimens he brought back saw Dampier return to buccaneering in 1703. While the Royal Navy may have tarnished his reputation, a consortium of British merchants mounted a two-ship expedition designed to raid treasure-laden Spanish ships off South America. The Spanish were distracted by the War of Spanish Succession (1701-1714), and Dampier's first voyage was as commander of St. George.

As with the Roebuck, there was disagreement among the crew, with some questioning Dampier's ability to lead and the seaworthiness of the St. George. The second ship, the Cinque Ports, was commanded by Thomas Stradling, and onboard was Scottish quartermaster Alexander Selkirk (1676-1721), who was marooned at his request on Juan Fernandez Island off Chile in 1704. Daniel Defoe based his main character in Robinson Crusoe on Selkirk, and Dampier ironically helped rescue the Scot in 1709.

Dampier was accused of having struck a secret deal with the Spanish, particularly when he allowed a ship laden with fine linen, wine, and valuables to continue on its way without seizing its cargo, but he returned to England at the end of 1707 with little to show for his plundering of enemy ships.

Dampier's Final Voyage

In 1708, Dampier took his third and final voyage, circumnavigating the world once more, again as a buccaneer. A Bristol-based consortium purchased two ships – the 30-gun, 320-ton Duke and the 26-gun, 260-ton Duchess. Dampier piloted the Duke; he was not the captain. The two vessels made their way around Cape Horn and into the south Pacific Ocean. Their final destination was Brazil.

As they came into view of Juan Fernandez in February 1709, smoke was seen rising above dense canopy. The captain of the Duke, Woodes Rogers (1679-1732), ordered a party ashore, only to find Alexander Selkirk in good health. Selkirk had adapted to the lonely life of a castaway but was put to work as second mate on board the Duke.

Dampier's final expedition was a rich one. A Manila galleon, the Nuestra Señora de la Encarnación y Desengaño – which translates to "Our Lady of the Incarnation and Disappointment" – was captured off the west coast of Mexico by Dampier and the privateer fleet on New Year's Day 1710. Its cargo consisted of musk, cinnamon, Chinese porcelain, silver plate, and jewels: a prize estimated at over £150,000 (or $200,000 today). Dampier and the fleet had been lying in wait for two months for Spanish treasure ships that plied the route between Acapulco in Mexico and Manila in the Philippines.

Dampier returned to London and died in 1715 at the age of 63, £2,000 in debt. Despite the prize of the Spanish galleon and its treasure, there were disputes over the share each man would get. Dampier passed at the home of his cousin, Grace Mercer, his wife Judith having died years earlier. He is remembered as a brilliant seafarer and navigator with a thirst for scientific knowledge and a curiosity for other lands and cultures. Charles Darwin included Dampier's books in his library aboard The Beagle, so his influence and contribution to the theory of evolution may be far greater than we will ever know.