William Henry Harrison (1773-1841) was an American statesman and military general who served as the ninth president of the United States. A member of the distinguished Harrison family of Virginia, he built his reputation as a war hero after defeating Tecumseh's Confederacy at the Battle of Tippecanoe (7 November 1811) – hence his nickname 'Old Tippecanoe'. In the US presidential election of 1840, the Whig Party nominated him as their candidate, and he defeated incumbent President Martin Van Buren (1782-1862) in the general election. Only three weeks after his inauguration, however, Harrison fell ill and died, becoming the first US president to die in office, as well as the president with the shortest tenure in American history. His grandson, Benjamin Harrison (1833-1901), would go on to serve as the 23rd president.

Early Life

William Henry Harrison was born on 9 February 1773 at Berkeley Plantation, the Harrison family tobacco plantation on the James River in Virginia which was worked by enslaved African Americans. He was the seventh and youngest child of Benjamin Harrison V (1726-1791) and Elizabeth Bassett Harrison. His father was a prominent planter and an ardent supporter of the Patriot cause during the American Revolution (1765-1789); indeed, the elder Harrison served as a delegate to the Second Continental Congress, was a signer of the Declaration of Independence, and was elected Governor of Virginia in the waning years of the American Revolutionary War. William Henry Harrison, therefore, would later claim to have been a 'child of the revolution', who had grown up with the birth of the United States taking place practically before his eyes (Harrison would, in fact, be the last US president to have been born a British subject before the Revolution).

He was tutored at home until the age of 14, when he was sent to receive a classical education at Hampden-Sydney College in Prince Edward County, Virginia. He studied there for three years, developing an interest in history, particularly ancient Roman warfare. In 1790, he travelled to Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, to study medicine under the supervision of Dr. Benjamin Rush (1746-1813), a leading American physician who, like Harrison's father, had signed the Declaration of Independence. William Henry Harrison was still in Philadelphia on 24 April 1791 when his father died; Berkeley Plantation was taken over by his eldest brother, Benjamin Harrison VI, who abruptly cut off funds for William's schooling. Finding himself suddenly without prospects, he appealed for help from a family friend, Virginia Governor Henry Lee III (1756-1818). Lee was able to procure Harrison an appointment as an ensign in the First Infantry of the newly formed US Army. Now 18 years old, Harrison was sent to Fort Washington, an outpost near Cincinnati (in present-day Ohio).

In 1792, Harrison was promoted to the rank of lieutenant and became aide-de-camp to General 'Mad' Anthony Wayne (1745-1796), the fort's commander and a hero of the Revolution. Wayne was in command of the US military forces engaged in the Northwest Indian War (1785-1795), a struggle for control of the expansive Northwest Territory between the United States and a loose coalition of Native American nations known today as the Northwestern Confederacy. On 20 August 1794, Wayne's soldiers decisively defeated the Native American forces at the Battle of Fallen Timbers. Though only an hour long, the battle decided the war in favor of the United States. Harrison distinguished himself in the fighting and was later commended by Wayne, who said that "Lieutenant Harrison…rendered the most essential service by communicating my orders in every direction…conduct and bravery exciting the troops to press for victory" (quoted in Freehling). Shortly thereafter, the Northwestern Indians were forced to sign the Treaty of Greenville (1795), which displaced them from Ohio and opened the Northwest Territory (present-day Ohio, Indiana, Illinois, Michigan, Wisconsin, and parts of Minnesota) to US colonization. For his role in this conquest, Harrison was promoted to captain and given command of Fort Washington in 1796.

Territorial Governor

During his time at Fort Washington, Harrison met 20-year-old Anna Symmes (1775-1864), a newcomer to the frontier whose father had just been appointed a judge in the region. Although Anna soon fell in love with the dashing young officer, her father disapproved, believing he could find her a wealthier match. The couple waited until Judge Symmes was called to another part of the territory before eloping on 25 November 1795. Upon his return, the judge was furious, demanding to know how the penniless Harrison intended to support his daughter. In response, Harrison placed his hand on the hilt of his saber and replied, "Sir, my sword is my means of support" (quoted in Freehling). The marriage would last until the end of Harrison's life and would ultimately produce ten children (including John Scott Harrison, father of future US president Benjamin Harrison).

Marriage into the Symmes family boosted Harrison's social status and lent him important political connections. In July 1798, President John Adams (served 1797-1801) appointed him secretary of the Northwest Territory. Despite the prestige that went with the position, Harrison found the work tedious and boring and sought a more exciting position in the national capital; in March 1799, he was chosen as the Northwest Territory's delegate to Congress. As a territorial delegate, he was not authorized to vote on legislation but could sit on congressional committees; as such, Harrison became chairman of the Committee on Public Lands and worked to make it easier to buy tracts of land in the Northwest Territory at lower costs. He also played a key role in dividing the Northwest Territory into smaller, more manageable sections. The eastern section continued to be called the Northwest Territory, while the western section, comprised of present-day Indiana, Illinois, Wisconsin, western Michigan, and part of eastern Minnesota, became known as the Indiana Territory. On 13 May 1800, President Adams appointed Harrison as the first governor of the Indiana Territory.

Harrison arrived at Vincennes, the territorial capital, on 10 January 1801 to begin his work as governor – he would be continually reappointed to the position and would serve for the next dozen years. In February 1803, he was directed by President Thomas Jefferson (served 1801-1809) to focus on obtaining lands from Native Americans for White settlement. Through a combination of coercion, bribery, and deception, Harrison managed to acquire 64 million acres of land from Native American nations over the course of a six-year period – the treaties he had them sign were incredibly lopsided in favor of the US government. In 1809, he negotiated the Treaty of Fort Wayne, in which he gained 2.5 million acres from the Delaware, Shawnee, Potawatomi, Miami, Kickapoo, and Eel River tribes. In the meantime, Harrison was also briefly made governor of much of the lands of the Louisiana Purchase, temporarily giving him the largest jurisdiction ever presided over by a US territorial governor. Almost as if celebrating his power, Harrison built a large, plantation-style manor near Vincennes that he named Grouseland, after the birds he hunted on the property.

War Against Tecumseh

Harrison's large-scale robbery of Native American lands would not go uncontested. In August 1810, 400 Native American warriors appeared outside Vincennes covered in war paint. They were led by Tecumseh (1768-1813), a charismatic Shawnee chieftain who had been busy building a confederacy of Northwestern tribes to resist US encroachment. Tecumseh had good reason to hate Harrison and his breed of White settlers – his beloved older brother, Cheeseekau, had been killed in battle with US soldiers, while Tecumseh himself had fought at Fallen Timbers and had witnessed the bitter displacement of his people that followed. Harrison's spies had brought him disconcerting reports of Tecumseh's growing confederacy, but President James Madison (served 1809-1817) had been too slow to provide the military resources he requested. Now, Governor Harrison had no choice but to receive Tecumseh and the other Native leaders at his Grouseland home and listen to their grievances. Tecumseh argued that the Treaty of Fort Wayne had been illegal – no Native American nation had the right to cede land to the US, he claimed, without the consent of the other nations in the confederacy. When Harrison refused to recognize this claim, Tecumseh lost his temper, leading men on both sides to draw their weapons. Though the situation was diffused, Tecumseh left Harrison with a dire warning – if the Treaty of Fort Wayne were not repudiated, he would seek an alliance with the British.

This was not an idle threat; British agents had been active on the frontier since the Revolution. Worried about the possibility of a British-backed Native American confederacy, Harrison decided to intimidate Tecumseh into submission with a show of force. On 6 November 1811, he led an army of 1,000 men to Prophetstown, the headquarters of Tecumseh's Confederacy, located near the confluence of the Tippecanoe and Wabash rivers. After arranging to meet with Tenskwatawa – Tecumseh's brother, known as 'The Prophet' – the next day, Harrison ordered his men to set up camp for the night. Early on the morning of 7 November, Tenskwatawa led over 500 warriors in an assault on Harrison's camp. Though the US troops were taken by surprise, they managed to repel the attack, sustaining significant casualties in the process. After the battle, Tenskwatawa and his followers abandoned Prophetstown, which was then burned to the ground by Harrison's troops. The Battle of Tippecanoe was hardly the glorious victory that Harrison would later claim, but it decisively destroyed the power of Tecumseh's Confederacy, which was never fully recovered. President Madison made sure to propagandize the victory, turning Harrison into a national hero and giving him his nickname of 'Tippecanoe'.

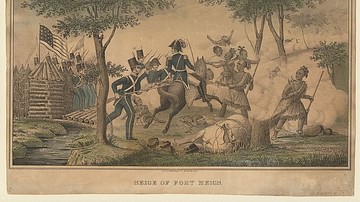

Shortly thereafter, the War of 1812 (1812-1815) broke out between the US and the United Kingdom. Early in the conflict, the British seized control of Detroit as well as the entire Michigan Territory, aided by a Native force led by Tecumseh. Promoted to major general, Harrison was put in command of the US Army of the Northwest and ordered to retake Detroit. The campaign initially went poorly; hampered by bad weather and muddy terrain, Harrison was unable to reach Detroit before winter set in. To make matters worse, the advance elements of his army under Brig. Gen. James Winchester were completely wiped out at the Battle of the River Raisin (18-23 Jan. 1813). The loss of such a large chunk of his army forced Harrison to go on the defensive. He pulled back to the Maumee River where he built Fort Meigs, only to come under siege by a British and Native American force under Sir Henry Procter and Tecumseh. The Shawnee chieftain taunted Harrison: "You talked like a brave man when we met," he wrote him, "but now you hide behind logs and earth like a groundhog" (Berton, 483).

Harrison managed to withstand the Siege of Fort Meigs (28 April to 9 May 1813) after the enemy ran low on supplies, though he found himself in no position to go on the offensive. This would change after the Battle of Lake Erie (10 Sept 1813), which destroyed British naval power on that lake. Now supplied by American ships on Lake Erie, Harrison was able to resume his campaign, retaking Detroit as Procter and Tecumseh reluctantly retreated into Canada. Harrison pursued and fought the climactic Battle of the Thames (5 Oct 1813), in which the British were defeated and Tecumseh was killed. The loss of the great chieftain marked the end of his intertribal confederacy, as well as any hope that the Northwestern Indians could resist US encroachment onto their lands. In 1814, Harrison resigned from the army after a disagreement with the Secretary of War. When hostilities came to an end in 1815, he settled on a farm in North Bend, Ohio, with his wife and children.

Postwar Political Career

In 1816, Harrison won election to the US House of Representatives. During his time in Congress, he expressed support for national banks, protective tariffs, and the extension of slavery. In 1818, he voted for a partial censure of General Andrew Jackson (1767-1845) for his reckless invasion of Spanish Florida. In 1819, Harrison was elected to the Ohio State Senate, and in 1825, he was elected to the US Senate. Constantly in debt, Harrison was always seeking higher-paying jobs in the federal government, leading President John Quincy Adams (served 1825-1829) to call him "the greatest beggar and the most troublesome of all office-seekers" (Encyclopedia Virginia). Despite his misgivings, President Adams appointed Harrison the first US minister to the new Latin American republic of Gran Colombia. Arriving in Bogotá in December 1828, Harrison was quick to offend his new hosts with his public criticisms of Simón Bolívar (1783-1830). When Andrew Jackson took office as president in March 1829, Harrison was recalled.

Harrison returned to his North Bend farm and spent the next eight years in quiet retirement. Then, in 1835, the newly formed Whig Party needed a strong presidential nominee to challenge the Democratic candidate Martin Van Buren, Jackson's vice president and handpicked successor. Many Whigs looked to Harrison for his name recognition and his status as a war hero. Harrison was one of four Whig candidates to run in the US presidential election of 1836. Though he ultimately lost the general election to Van Buren, Harrison made a strong showing, winning more votes than the competing Whig candidates. His loss in 1836 turned out to be a blessing in disguise – shortly after Van Buren's inauguration, the country was struck by an economic depression dubbed the Panic of 1837. The Democrats received much of the blame for the crisis, with the president referred to disparagingly as 'Martin Van Ruin'. The stage seemed set for a Whig victory in 1840.

Bid for the Presidency

On 4 December 1839, Harrison won the nomination at the Whig national convention at Harrisburg, Pennsylvania; his name recognition and lack of political baggage helped him beat out his rival, Henry Clay (1777-1852), for the nomination. To appeal to Southern Democrats, the convention nominated former Virginia senator John Tyler (1790-1862) as Harrison's running mate. Borrowing techniques from revivalist preachers, the Whigs went from town to town whipping up public support with torchlight parades. They would hold speeches beneath large tents in which the speaker would make emotional appeals to the crowd, reminding them of the economic troubles brought on by the current administration. Each speech would then be followed by a political song such as 'Van, Van, Van Is a Used-up Man' or the more famous 'Tippecanoe and Tyler Too!'.

The Democrats attempted to strike back by declaring that Harrison was too old for the presidency. "Give him a barrel of hard cider," wrote one Democratic newspaper, "and settle a pension of two thousand a year on him, and my word for it, he will sit the remainder of his days in his log cabin" (quoted in Howe, 574). This backfired, however, as Harrison's campaign seized the opportunity to present their candidate as a common frontiersman. From then on, no Harrison rally was complete without barrels of hard cider and miniature log cabins. When the election finally took place, Harrison won 234 electoral votes compared to only 60 for Van Buren. The Whigs rode his coattails to majorities in both the House and the Senate, the only time in their short history that the Whig Party controlled both the executive and legislative branches of government at once.

Presidency & Death

On 9 February 1841 – his 68th birthday – Harrison arrived in Washington, D.C., the first president-elect to do so by train. He stopped by the White House to dine with outgoing President Van Buren and spent the following weeks writing his inauguration speech, diligently practicing it while out on his daily horseback rides. On Inauguration Day, 4 March, he led a grand parade that included floats and military bands up to the Capitol Building, where he gave his speech; clocking in at 8,445 words, it remains the longest inauguration speech in US history. He spoke for nearly two hours and, despite the cold, wore no overcoat, hoping to shake off the rumors that he was too old and frail. No sooner had he been sworn into office than Harrison was swarmed by office seekers and Whig politicians who wanted to press their party's agenda on him. Once, when Henry Clay got a little too pushy at a meeting, Harrison snapped, "You forget, Mr. Clay, that I am the president!" (quoted in Howe, 589).

Harrison felt it was his duty to meet with everyone who sought him out, leaving him quickly overwhelmed. The overwork took its toll; on 24 March, he fell sick with a cold and, two days later, a team of physicians was summoned to treat him for pneumonia. Harrison's condition steadily worsened until he died on 4 April 1841, exactly one month after his inauguration. He was the first US president to die in office, leading to a constitutional crisis. The Constitution was unclear as to whether the vice president officially became president upon a predecessor's death or simply assumed the 'powers and duties' of that office. Harrison's cabinet insisted that Tyler was merely the 'acting president', which Tyler disputed, believing he was entitled to the office itself. The issue was decided by Chief Justice Roger B. Taney, who ruled that Tyler would assume office after taking the presidential oath, which he did on 6 April 1841. Harrison, meanwhile, lay in state in the Capitol before his remains were ultimately interred in North Bend, Ohio.