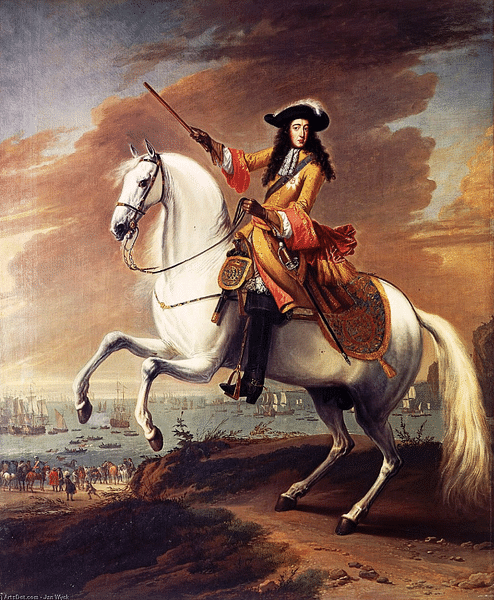

William III of England (also William II of Scotland, r. 1689-1702) became king of England, Scotland, and Ireland after the Glorious Revolution of 1688. Protestant William, Prince of Orange, was invited to rule jointly with his wife Mary II of England (1689-1694), daughter of the deposed James II of England (1685-1688), who was Catholic. William spent much of his reign in an indecisive war with France and he was not popular in his adopted kingdom.

Early Life

William of Orange was born on 4 November 1650 in Binnenhof Palace, The Hague. His father was William II of Orange and his mother Mary Stuart, the daughter of Charles I of England (r. 1625-1649). William's father died before he was even born, and he lost his mother when he was just 10 years old. Both parents had succumbed to smallpox. Consequently, William became Prince of Orange immediately, a name which derives from the small principality near Avignon in southern France. William's precise role as Prince of Orange is described here by the constitutional historian R. Starkey:

The head of the House of Orange was not sovereign in the Dutch Republic, but first among equals. Sovereignty instead resided in the Estates of the seven provinces. But ever since William the Silent's leadership of the Dutch Revolt against Spain in the late sixteenth century, his descendants as princes of Orange had traditionally been made stadholder or governor of each of the provinces and captain-general and admiral of the armed forces of the republic.

(367)

The Dutch royal house was in decline, there were powerful anti-royal voices in the Netherlands, and the country was under threat from France, but William's strength of character and ties with England would be his salvation. The prince visited England in 1670, he was presented with two honorary university degrees, and he had an audience with his uncle Charles II of England (r. 1660-1685). The English king's family relations did not prevent him from going to war with the Netherlands in 1672. During this conflict, William became Captain and Admiral-General of the combined Dutch armed forces. In 1675, the prince was wounded in the arm fighting the French, and that after surviving a bout of smallpox the year before.

The Glorious Revolution

William's main concern for the Netherlands was that this collection of states was under an ever-more serious threat from Catholic France, which was expanding its territory across the European continent. The Dutch navy could not fight both England and France together. This was one of the reasons William married Princess Mary, the daughter of (future) James II at Whitehall on 4 November 1677. Mary was considered something of a beauty, while William was short, hunched, had a hooked nose and black teeth, and his character was no improvement, being taciturn and humourless. Despite the physical disparity, the couple did eventually build a strong bond, although William kept at least one mistress (Elizabeth Villiers), and there were rumours that his taste ran to young men. The diplomatic significance of the marriage seemed to have its desired effect when Louis XIV of France (r. 1643-1715) signed a peace treaty with the Netherlands in 1678.

William was a Calvinist Protestant, and Mary had been brought up a Protestant on the insistence of the English Parliament, which feared her Catholic father James (he had converted in 1668) had plans to reinstate Catholicism as the state religion when he succeeded his elder brother Charles II of England. Indeed, when James became king in 1665, he began to place Catholics in prominent public positions and insisted certain Catholic practices be tolerated. Further, the king was an authoritarian who ignored certain laws and who was biased in the application of others when it suited. James even dismissed Parliament in November 1685, and that body was never to be recalled while he sat on the throne. The final straw came when James finally had a son, born on 10 June 1688: James Francis Edward. The king was Catholic, the queen, Mary of Modena (d. 1718), was Catholic, and now, surely, the heir would be Catholic.

When in June 1688 prominent Protestant figures in England invited William of Orange to invade and become king, he gladly accepted. William was the grandson of Charles I of England and the son-in-law of James II, he was Protestant, and the Netherlands could be a very useful ally with its powerful navy and trade connections. The Prince of Orange was already planning an invasion even without the invitation, and he said he had merely been waiting for a favourable "Protestant wind". The ever-present threat from France had allowed William to disguise his build-up of 60 warships as a purely defensive precaution.

William would have been encouraged by two rebellions early on in James II's reign: the Argyll Rebellion in Scotland in May 1685 and the Monmouth Rebellion in the southwest of England in June-July of the same year. Both were relatively minor affairs and easily quashed when their respective leaders were caught and executed, but they did show William he would gain at least some support for a regime change back to a Protestant monarchy. Support and public celebrations of the acquittal of several prominent Protestant bishops whom James had hoped to imprison was another indication that the kingdom was far from unified in its support of the status quo.

Invasion

William's first attempt to reach England by sea was scuppered by stormy weather, but he persisted and landed with an army of 15-21,000 men in Devon on 5 November 1688. The army was an experienced fighting force and made up of Dutch, English, Scots, Danes, Huguenots, and even a contingent from Suriname. The prince also took a printing press so that he might more easily spread pro-Protestant propaganda. When he landed at Brixham, William reassured the Englishmen he met that "I come to do you goot. I am here for all your goots" (Cavendish, 338).

William marched slowly east towards London through unfavourable weather. Meanwhile, James was left isolated, deserted by former supporters like John Churchill and even his own daughter Anne. The queen left England for the safety of France in December. James suffered more important desertions amongst his top army staff, and there were immediate uprisings in favour of William in Cheshire, Yorkshire, and Nottinghamshire. Then after being hit with a bizarre series of nosebleeds, the king decided to abandon the battlefield and follow his wife. The king may have been suffering a mental breakdown at this point as he became utterly convinced he was destined to suffer the same terrible fate as his father. Queen Mary made it across the Channel, but the king did not, despite his disguise as a woman. He was spotted by fishermen and taken captive in Kent. William was by now in London, and he decided the best thing to do with his rival and father-in-law was to allow him to leave for France as he had wished. William had achieved the remarkable feat of heading the first successful invasion of England since his namesake William the Conqueror (r. 1066-1087) in 1066.

A Constitutional Monarchy

The official line was that James had abdicated, and Parliament recorded the removal of the monarch as occurring on 23 December 1688, the day James had left English shores. William became William III of England via a decree by Parliament on 13 February 1689. This change of regime became known as the Glorious Revolution because it had occurred entirely peacefully (or almost, there were some episodes of Catholic houses and chapels being attacked during William's march to London). There had certainly been no battles or country-wide uprisings in support of either side. Whig historians (pro-Protestants) also believed the revolution 'glorious' because it had preserved the existing institutions of power, which was true, but the relationship between these institutions was altered, a change which only grew more significant over time.

There were some limitations to William's golden prize. The first was that William had to rule jointly with his wife, now Mary II of England, although in practice he alone had sovereign power. The 'Whigs' in the House of Commons (Parliament’s lower house) wanted a joint rule between William and Mary. Mary's own view was that William should rule as regent for her father, she had no ambition to rule alone. The 'Tories' in the House of Lords (the upper chamber of Parliament) had wanted Mary to rule alone as this preserved the tradition of succession but William would not settle for anything less than a proper king's role. Accordingly, William III of England and Mary II of England were crowned in a joint coronation ceremony in Westminster Abbey on 11 April. Their joint reign is often simply called 'the reign of William and Mary’ and newly-minted coins showed the two monarchs together.

The second limitation was imposed by Parliament as a new form of government was devised, a constitutional monarchy. Over the next few years, a whole barrage of laws passed by Parliament limited the monarchy's powers. Gone were the days of authoritarian monarchs who could dismiss Parliament on a whim. Now the two institutions ruled in unison, an arrangement established by the Bill of Rights of 16 December 1689.

Parliament had the ultimate authority in the key areas of passing laws and raising taxes. It also became much more involved in accounting how money was spent for state purposes, particularly on the army and navy. The monarchy was now supported not by the taxes they could raise or the land they could sell but by the money from the Civil List issued by Parliament beginning with the Civil List Act of 1697. The king lamented in private "The Commons used him like a dog…Truly a King of England…is the worst figure in Christendom" (Starkey, 401).

William may not have liked this control on his purse strings, but it meant he could not, as so many of his predecessors had done, dismiss Parliament for long periods and only call it back when he ran out of cash. And the king needed lots of cash since he was determined to use his new position to finally face the French on the battlefield and at sea and end their domination of Europe. Thus began the hugely expensive Nine Years' War (1688-1697), which saw the League of Augsburg (later called the Grand Alliance and composed of such powers as the Netherlands, Holy Roman Empire, and Britain) face France. The war had no clear winner, but William did suffer bad defeats at Steenkerke in 1692 and Neerwinden in 1693. The king gained a notable victory against the French at Namur in September 1695. The war came to an end with the Treaty of Ryswick, signed on 20 September 1697, which amongst other points, finally saw Louis XIV of France (r. 1643-1715) recognise William as the rightful king of England, Scotland, and Ireland.

Meanwhile, the list of limitations on William in Britain continued. No monarch could henceforth maintain their own standing army, only Parliament could declare war, and any new monarch had to swear at their coronation to uphold the Protestant Church. No Catholic or individual married to a Catholic could ever become king or queen again. To ensure Parliament did not itself abuse the power bestowed upon it, there were to be free elections every three years and a guarantee of free speech in its two Houses. Finally, the May 1689 Toleration Act, although it did not go as far as Calvinist William had hoped, protected the rights of Protestant dissenters (aka Non-Conformists) who made up around 7% of the population. After a period of persecution under the Stuarts, they could now freely worship as they wished and establish their own schools. The Toleration Act did not apply to Catholics or Jews.

Ireland & Scotland

James II was not dead but in exile, and eventually, encouraged by Louis XIV, he made an attempt to get his throne back. Landing in Ireland in March 1689, James had some early success, but a 105-day siege of Protestant Londonderry (Derry) failed. Then the arrival of the king in person with a large English-Dutch army, which was superior to James' in both weapons and training, brought final victory at the battle of Boyne on 1 July 1690. Ireland was 75% Catholic, and although a guerrilla war rumbled on, the country found itself once again with a Protestant king, and a peace was signed, the Treaty of Limerick, on 3 October 1691.

In Scotland, Jacobite support (for James II, from the Latin Jacobus) had been particularly strong in the Highlands, but in the cities, there was more support for Protestant William. When the Prince of Orange had first landed in England, there were shortly afterwards sympathetic riots in Edinburgh, where Catholics and their property were attacked. A Convention met to decide who to support and the decision was made on 11 April 1689 to favour William. At the same time, the Claim of Right established the monarchy there on similar terms as declared in the English Bill of Rights. Mary and William ruled jointly in Scotland when they accepted the crown there on 11 May 1689. There was a Jacobite rising led by Viscount Dundee which defeated a pro-William army at Killiecrankie on 27 July 1689. Then there was a reversal on 21 August at Dunkeld, where 'Bonnie' Dundee was killed. In the meantime, the government of Scotland was established under the control of the Presbyterian Church.

In February 1692, the divisions in Scotland were widened when James' supporters the MacDonald clan had its leaders massacred at Glencoe by the Campbells. This tragic incident was all based on a misunderstanding since the MacDonalds had been on their way to swear allegiance to the new king but had been delayed by a snowstorm; their delay was taken as a refusal of loyalty by the Campbells. James II died in exile in France in 1701, but his son James (the Old Pretender) and grandson Charles (the Young Pretender) both carried on the flame of rebellion in the Highlands. However, two Jacobite risings in 1715 and 1745 failed, and there was no way back for the troubled Royal House of Stuart.

Reign with Mary

The royal couple made a good team. Mary represented continuity with the Stuart line, Englishness, and piety, while William, despite a lack of warmth from his adopted subjects, at least represented Protestant military power. As the king himself stated: "He was to conquer Enemies, and she was to gain Friends" (Starkey, 404). William was known for his abrupt manner and very short audiences. The king suffered badly from asthma, and for this reason, he avoided London and Whitehall Palace with its damp air from the River Thames. The couple preferred to build a new home together and so they converted Nottingham House to Kensington Palace. Another favourite residence was Hampton Court. William's main pastimes included hunting, creating formal gardens, and collecting furniture.

Both William and Mary sought to modernise the monarchy. Both were against some of the more dubious traditions associated with the supposed mystical power of sovereigns. One of these was the 'King’s Touch', the belief that a king or queen could cure certain illnesses merely by touching the sufferer. William abolished the tradition entirely. William also abandoned the tradition of the monarch washing the feet of commoners on Maundy Thursday.

It was to prove a short joint reign. Mary contracted smallpox in December 1694, and she died in Kensington Palace on the 28th of that month. The late queen was buried in Westminster Abbey after an impressive ceremony notable for its music composed by Henry Purcell (d. 1695). William was distraught at Mary's death aged just 32, and he refused to marry again. When formally offered the condolences of MPs in Parliament, the king was so overcome with emotion he was unable to reply. In 1696, the king survived a kidnap and assassination attempt by Jacobite sympathisers, but, if anything, this provoked a rising in public sympathy for William. Nevertheless, a mutual suspicion remained between sovereign and subjects, one of the reasons the king insisted on maintaining a personal guard made up of Dutch Blue Guards (until Parliament ordered their removal in 1699).

Death & Successor

William died on 8 March 1702 at Kensington Palace. He had suffered an infection as a result of falling from his horse and breaking his collarbone in February. The king's horse had tripped over a molehill in Richmond Park, a triviality that caused the king's death within two weeks. The king was buried in Westminster Abbey after an unusually low-key midnight funeral service, which illustrated more than anything else that William had never been fully accepted by his subjects.

William and Mary had suffered three stillborn babies and so they had no direct heir. Consequently, Mary's younger sister Anne (b. 1665), who had been the official heir since February 1695, became queen, and she then reigned over a united kingdom as Queen of Great Britain and Ireland from 1707 to 1714. Anne, Queen of Great Britain, was the last of the Stuart monarchs and was succeeded by George I of Great Britain (r. 1714-1727) of the House of Hanover. The joint strength of monarchy and Parliament, mixed with financial reforms and heavy investment and modernisation of the Royal Navy, now the most powerful in the world, meant that Britain entered the 18th century ready to take on the world and build an empire of unprecedented size and wealth.