William II of England, sometimes called William 'Rufus' for his red hair and complexion, reigned as the king of England from 1087 to 1100 CE. The son of William the Conqueror (r. 1066-1087 CE), the younger William was loyal to his father, unlike his elder brother Robert Curthose, and so it was he who inherited the crown of England. William and Robert, who became the Duke of Normandy, would later battle for control of each other's territory, but they eventually reached a reconciliation. Put down in the history books as an unpopular king who lived the high life while fleecing the state and Church, he at least consolidated the gains of his father and permitted his successor, another brother, Henry I of England (r. 1100-1135 CE), to enjoy a long and largely peaceful reign which gave the country some much-needed stability following the turbulent Norman Conquest of England.

Family Relations

William was born c. 1056 CE in Normandy, his father being William, Duke of Normandy, otherwise known as William the Conqueror or William I of England following his invasion of that country in 1066 CE. The young William's mother was Matilda of Flanders (c. 1032-1083 CE), who was the daughter of the Count of Flanders and the niece of Henry I of France (r. 1031-1060 CE). Matilda would be crowned the Queen of England in Westminster Abbey on 11 May 1068 CE. William was one of four brothers, and it was the eldest, Robert Curthose, who proved most troublesome for his father.

William was known as Rufus (from the Latin for red) because of his hair colour and ruddy complexion. As a youthful prince, William campaigned in Wales with some success in 1075 CE, subduing the Welsh king Caradog ap Gruffudd (d. 1081 CE). That victory would inspire him to try and complete the conquest of Wales when he became king.

William remained loyal to his father during his brother Robert's rebellion of 1078 CE. Robert had wanted more lands and power of his own, and he was supported by Philip I, king of France (r. 1060-1108 CE), eager to destabilise the dangerously expanding Norman Empire. Philip gave Robert the castle of Gerberoi on the border between France and Normandy to use as his base. The king, William the Conqueror, besieged the castle but was defeated by a force led by Robert in a field engagement. Father and son then reconciled and, in 1079 CE, Robert was sent off to Northumbria to stop the repeated raids there which came from Scotland. Robert remained ambitious, though, and he sided with the enemy against his father at the siege of Mantes in 1087 CE. These family troubles were not good for the kingdoms of either England or Normandy but they were good news for William Rufus who was now his father's favourite and most likely successor.

Succession & Securing the Kingdom

Following his father's death of natural causes while campaigning in France on 9 September 1087 CE, William would be crowned king on 26 September of the same year in Westminster Abbey. Robert Curthose, meanwhile, inherited the title Duke of Normandy and the lands that went with it. A third brother, Henry, received cash instead of lands. The fourth brother, Richard, had died in 1075 CE. Consequently, the Norman kingdom was now split in two geographically and all three brothers would bicker for supremacy over the next two decades.

William might be king but he still had to carry on the work of his father and consolidate Norman rule in England and parts of Wales and Scotland. His father's many motte and bailey castles had to be maintained and a new one was built at Carlisle. Successful campaigns in Wales in 1093 CE secured the loyalty of several Welsh princes, while in the north, Cumbria was annexed and Scotland was made more friendly in 1097 CE by replacing the hostile King Donald III (r. 1093-1094 CE) with his more amenable nephews Duncan II (r. 1094 CE) and Edgar (r. 1097-1107 CE). William had supported the latter pair with an army, which allowed them to dethrone their uncle.

William's uncle, Odo of Bayeux (d. 1097 CE), who had been made Earl of Kent by his half brother William the Conqueror, was an ambitious and dangerous relative. Odo had once become the second most powerful man in England but he had fallen out of favour with William I and only received forgiveness when the Conqueror was on his deathbed. Odo then supported Robert Curthose in his claim for the English crown against William II and so the new king had no time at all for the unscrupulous former earl. The rebels were defeated, and Odo lost his control of Rochester Castle to a siege in 1088 CE, his lands were confiscated, and he was permanently exiled from England. Odo died in January 1097 CE in Sicily on his way to participate in the First Crusade (1095-1102 CE).

In 1091 CE, William then invaded Normandy and the ever-opportunist Robert capitulated and sided with his brother-king, the pair even joining forces to defeat the third brother Henry at Mont-Saint-Michel and then divide the loser's lands in the Cotentin (Cherbourg) peninsula amongst themselves. Robert then pawned his duchy to William in order to pay for his planned expedition to join the First Crusade. Robert set off in 1096 CE and it seemed that finally, William had undisputed possession of a settled kingdom.

William, the Church & Taxes

William's wild lifestyle soon upset figures in the Church, a situation not at all helped by the king's avoidance of appointing new bishops and abbots in order to keep Church revenues for himself. The king even refused to nominate a new Archbishop of Canterbury between 1089 and 1092 CE over a dispute about who supported which Pope (there being two rivals for that post at the time). Certainly, William was not too fussy how his underlings - notably the chief minister Ranulf Flambard - filled the state coffers, and this did upset a lot of barons. So much so, William's harsh fiscal policies and heavy taxes to pay for his military campaigns did lead to a murder plot in 1095 CE. The idea to replace the king with his first cousin, the count of Aumale, came to nothing, though. The king then embarked on a fearful witch-hunt of the conspirators which led to tortures, mutilations, and executions. In a typical episode of financial opportunism, Flambard used the occasion to fine nobles left right and centre and so bring yet more money into the state treasury.

William's hot temper, sarcastic wit, and short physique seemed to have cost him a favourable portrayal in most history books where he often appears as a roistering good-time Charlie who was rather too fond of wine and the results of his passion for hunting. The unflattering depiction may, though, have more to do with the bias of religious chroniclers upset with the king for his treatment of their archbishop. They even charged William with being a pagan and spreader of witchcraft. Rufus was also accused of being a homosexual, significantly, a charge only declared after his death, and really the only evidence he might have been is that he did not marry, hardly a conclusive point.

A more reliable legacy William left was the Great Hall at the main royal residence at Palace of Westminster. Built in 1097 CE and then extended upwards with a new roof by Richard II of England (r. 1377-1399 CE), William's hall measures 73 x 20.5 metres (240 x 67.5 ft), the largest such structure in Europe at the time of its construction. In the building's inaugural procession in 1099 CE the Welsh royalty was forced to proceed William carrying his ceremonial sword, a bit of propaganda to demonstrate the increasing power of the English throne in Britain.

Death & Successor

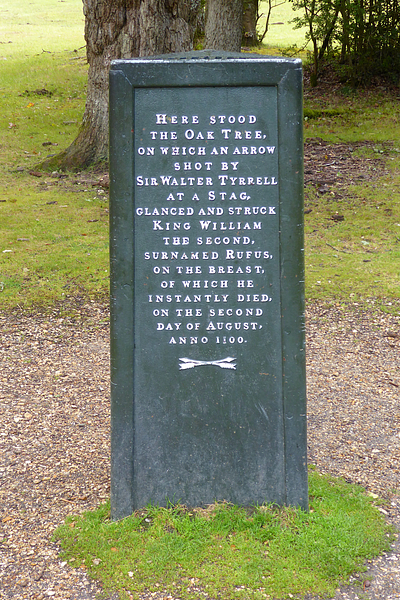

William II died on 2 August 1100 CE in the New Forest, as the result of a hunting accident when the nobleman William Tirel (sometimes spelt Tyrrell) fired a fateful arrow which bounced off the back of a fleeing stag and landed right in the centre of William's chest. At the time, the incident was regarded as an accident and Tirel was not punished for his part in the tragedy. It is, nevertheless, curious that William's younger brother and successor Henry was in the hunting party and Robert Curthose was just then away fighting in the First Crusade, allowing Henry to forward himself as the next king. The Church had another explanation and blamed the harsh forest laws imposed by William's father. In short, the king had received divine punishment for royal greed (and not living a very clean life). A third explanation is the king was shot by a poacher, angry at the brutal mutilation punishments dished out to anyone who even scared animals in the king's hunting reserves, never mind those who were caught killing them. It is perhaps significant that the very park where William was killed had been created by his father and so many locals would have well remembered the days before the Conquest when the forest animals had been open game.

Whether accident or intention, the king was dead, and he was buried under the tower of Winchester Cathedral. Unmarried and without children, William's throne was taken by Henry who had not been slow to secure the royal treasury and his election by the ruling council, all within 48 hours of his brother's death. Thus, on 6 August 1100 CE, Henry I of England was crowned in Westminster Abbey. The king would defeat his brother Robert (back from the Crusade) at Tinchebrai in Normandy in 1106 and go on to rule his unified kingdom of Normandy and England with some success until 1135 CE. Finally, in an interesting footnote, the tower under which William Rufus was buried in Winchester Cathedral collapsed in 1107 CE, another indicator, the pious medieval chroniclers pointed out, of God's wrath on a pagan king who did not take care to exercise his divine right for the good of his people.