William IV of Great Britain (r. 1830-1837) succeeded his elder brother George IV of Great Britain (r. 1820-1830) to become the fifth Hanoverian monarch. William had a successful naval career, and his reign is best remembered for the democratic reforms initiated by the 1832 Reform Act. He was succeeded by his niece, Queen Victoria of Great Britain (r. 1837-1901).

The House of Hanover

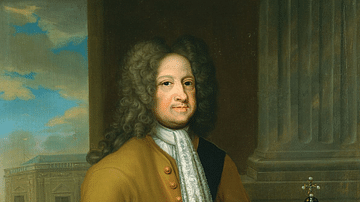

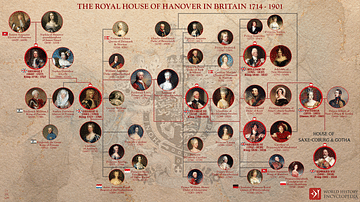

The royal house of Hanover had taken over the British throne in 1714 following the death of Queen Anne of Great Britain (r. 1702-1714), who had no children. The Hanoverians were also electors of Hanover, a small principality in Germany, and so both George I of Great Britain (r. 1714-1727) and George II of Great Britain (r. 1727-1760) were very much Germans ruling in Britain. George III was the first Hanoverian to be born in Britain and to speak English as his first language, and he was, consequently, more popular with his subjects. The next king, George IV, was much less popular because of his poor treatment of his wife Caroline of Brunswick-Wolferbüttel (d. 1821) and his incessant overspending.

Early Life & Family

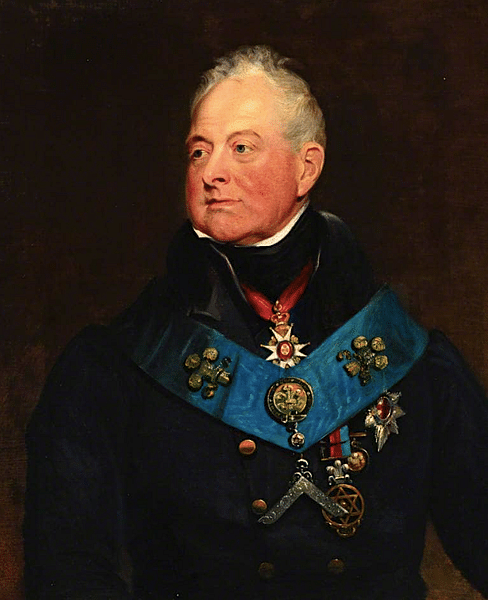

William was born on 21 August 1765 at Buckingham Palace. His father was George III, and his mother was Charlotte of Mecklenburg-Strelitz (1744-1848). He had many siblings, amongst them his elder brother George, born in 1762, and another elder brother, Frederick (b. 1763). Third in line to the throne and so unlikely to ever find himself sat upon it, William, at the behest of his father, joined the Royal Navy in 1778 when he was still just 13 years of age. William joined as a lowly midshipman and did well, reaching the rank of Rear-Admiral by the age of 24 and becoming friends with England's great naval hero Horatio Nelson (1758-1805). William gained his first command in 1786, Pegasus. In 1789, he was made the Duke of Clarence, and by 1790, he no longer had to serve at sea. His naval career was not over, though, since, in 1811, he was promoted to Admiral of the Fleet. In 1827, he reached the very top when he was given the largely political appointment of Lord High Admiral, the figurehead of the Royal Navy. Unfortunately, the tough-talking sailor made a pig's ear of the diplomacy and political machinations his new post required, and he was obliged to resign after a year.

On 11 July 1818, William married Adelaide of Saxe-Meiningen (1792-1849), 27 years his junior and daughter of the Duke of Saxe-Meiningen. The couple had two daughters, but both of these died in infancy. William had ten illegitimate children with his long-term mistress, the comic actress Dorothy Jordan. The couple's children carried the surname FitzClarence. Prince George, meanwhile, had become regent for his mad father in 1811 and king in his own right in 1820 as George IV. The king had had one legitimate child, a daughter, but she died in childbirth in 1817. Consequently, when George IV died of a ruptured blood vessel on 26 June 1830, the next in line was William since his elder brother Frederick, Duke of York had died three years before. At 66 years old, the Duke of Clarence became William IV of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland. He also inherited the family title of King of Hanover.

William's coronation ceremony was held on 8 September 1831 in Westminster Abbey, and it was deliberately less extravagant than the previous coronation to try and win over the public who had become rather tired of watching royal overspending. This reduction in pomp was so evident, William's ceremony gained the nickname of the "half-crownnation" after the small half-crown coin.

William was more popular than his big-spending predecessor, who had further alienated himself from his subjects by banishing his wife from his presence and refusing to allow her at his coronation. The new king, who liked neither party politics nor the arts, was another colourful addition to the House of Hanover, as here described by R. Cavendish:

Those close to William thought him crotchety, irascible and obstinate. He had a head shaped like a coconut and he had been unkindly nicknamed 'Silly Billy' ... He was considered a character – a bluff, patriotic jack tar who spoke his mind, disliked ceremony and fuss, and detested foreigners, especially the French.

(392)

The king looked striking with his unusual hairstyle of a large quiff, and he was a bit of a chatter-box with "a tendency to talk at length and at some distance from the point" (Starkey, 451). William was certainly popular with those around the royal residences. He had the habit of walking around London and Brighton rather than being closed in within a carriage. On his birthday in 1830, the king held an outdoor lunch for 3,000 poor people who were served such treats as veal and plum pudding. William also gave the public access to the Great Park of Windsor.

Political Reforms

William's reign was short, but it witnessed important and far-reaching developments in the democratic system and society. There was the abolition of slavery across (most of) the British Empire from 1833, the culmination of a long process of legislation to limit slavery. The territories of the East India Company in India and elsewhere were exempt, and slave owners elsewhere were compensated financially. Another important improvement in society was the prohibition of child labour in factories. Finally, the 1832 Reform Act was passed, a real milestone in electoral legislation.

The Reform Act swept away the rotten boroughs, those areas where a Member of Parliament could win a seat by simply paying for votes, such was their low electorate. Reflecting changes in British society and industry, the Reform Act also gave political representation to the new and booming manufacturing centres like Birmingham and Manchester, which, incredibly, had had no representation at all while tiny rural constituencies sometimes had not one but two MPs. Wealthier middle-class men could now run for election to Parliament as the power of the great landowners dwindled. At last, the electoral system was beginning to reflect the population and social changes in Britain of the last two centuries.

William was instrumental in getting the Reform Bill passed into law as an Act of Parliament. First, in order to relieve the political impasse between the two main parties of Whigs and Tories (the latter opposed the reforms) in the House of Commons, he dissolved Parliament, which brought about a new general election and a larger Whig majority. This got the bill through the lower chamber, but Parliament's upper chamber, the House of Lords, remained dead against any reforms. The then prime minister Earl Grey (1764-1845) asked the king to create (or, as it turned out, only threaten to create) a number of new peers sympathetic to the reforms and so allow it to pass the scrutiny of the Lords. The king had been reluctant to promise such a thing, but he realised it was the only way to pass the bill. To his credit, William noted that, allowed to choose for himself, he would have refused the request but "as a sovereign it was his duty to set those feelings and prejudices aside" (Cannon, 336). The political manoeuvring may have brought valuable and necessary reforms, but the way they were achieved had set a dangerous precedent where a monarch's liberty to select peers could be heavily influenced by prime ministers for short-term political expedience. It was yet another case of Parliament nibbling away at royal power, a trend that had already become the constitutional legacy of the Hanoverians.

Parliament Destroyed

There was one notable disaster during William's reign. A great fire, caused by an overheated stove, destroyed the Houses of Parliament on 16 October 1834. This catastrophe was, at least, an opportunity to build a grander home for the nation's government – the old building had been compared to a ramshackle coffee house by several visiting foreign rulers. The celebrated artist J. M. W. Turner (1775-1851) captured the building in flames in two famous paintings, now in the Philadelphia Museum of Art and Cleveland Museum of Art. The king, still preferring his old residence Clarence House to the ostentatious vastness of Buckingham Palace, offered the latter to the politicians while their parliament was rebuilt (they refused).

In many ways, the fire and necessary physical renewal of Parliament reflected the sweeping electoral reforms for which William's reign would be best remembered. The British monarchy was about to undergo a major renewal, too, as the Hanoverian kings gave way to a young girl who would become the longest-serving British monarch the country had yet seen.

Death & Successor

William IV died of cirrhosis of the liver and pneumonia on 20 June 1837 at Windsor Castle. He was buried in St. George's Chapel, Windsor. The king, without any legitimate children of his own, was succeeded by his niece Queen Victoria, daughter of George III's late son, Edward, Duke of Kent (1766-1820). The king had got on well with his niece and heir, even if he could not abide her mother Marie Louise Victoria, Duchess of Kent. The king had been determined, despite his ailing health, to live long enough for Victoria to reach maturity so that her mother could not promote herself as regent. William achieved his goal but only just. Victoria reached 18 just one month before the old king died.

The succession of Victoria finally split Hanover from the British throne as no female was permitted to rule the German principality if there was a male heir, no matter how remote. Accordingly, George III's fifth son Ernest Augustus, Duke of Cumberland and Teviotdale (1771-1851), became the new King of Hanover, where he permanently resided. Victoria was the last of the British Hanoverians as her children were classed as part of the new dynasty of Saxe-Coburg & Gotha (which was later renamed Windsor), her husband, Prince Albert's family.