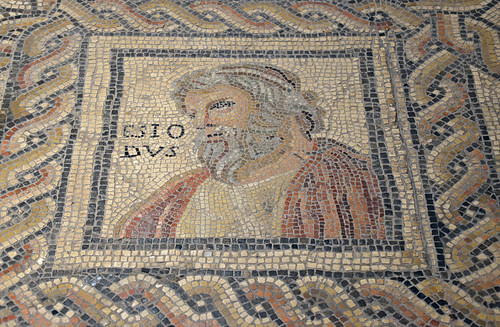

Works and Days is an epic poem written in dactylic hexameter, credited to the 8th-century BCE Greek poet Hesiod. Hesiod is generally remembered for two epic works, Theogony and Works and Days but, like his contemporary Homer, he was part of an oral tradition and his works were only put into written form decades after his death. Work and Days is a tribute to the benefits of a life devoted to work and prudence. In the poem, Hesiod speaks directly to his brother Perses on how to conduct his life; a brother who had taken a larger share of their inheritance.

Authorship

Very little is known of Hesiod's life. His father emigrated from Cyme in Asia Minor and settled in Boeotia, a small state in central Greece. His earliest known work Theogony traced the history of creation, Chaos, to the ascension of Zeus as the absolute ruler of the Olympian gods. Although there is some dispute concerning his authorship of Works and Days, classicist Dorothea Wender in her translation of Hesiod believes him to the author of the later and far superior work. While Theogony has historical interest, “… if the reader wants to find the work of a real poet, he should turn to the Works and Days” (19). Centuries later, both poems would have a substantial effect on the Roman poet Ovid and his Metamorphoses.

Justice of ZEUS

Speaking from his own personal experiences, Hesiod praises the benefits of an agrarian life while condemning his brother's wasted life at sea. Although Wender considers his advice to be both sincere and probably correct, she still referred to Hesiod as “grouchy.” However, while he may seem grouchy, he believed in justice, honesty, piety, self-reliance, and most of all work. He disliked city people, the sea, women, gossip, and laziness. In the opening lines of the poem, he made a plea to Zeus, the Thunderer, to let his brother, who at that time was on a merchant ship, to hear the truth.

Primary among Hesiod's sacred principles was the concept of justice, and to him, Zeus was the utmost representation of justice. According to historian Thomas Martin in his book Ancient Greece, Hesiod viewed justice as a divine quality – embodied in Zeus – that would punish evildoers. However, to Martin, Homer's Zeus was only concerned with the fate of his beloved warriors in battle; a trait evident in both the Iliad and Odyssey. Historian Norman Cantor in his book Antiquity said that while Homer may be credited with creating the Greek image of the gods and giving them both personality and function, Hesiod demonstrated that they were a moral force, champions of justice. Concerning the power of Zeus, Hesiod wrote:

With ease he strengthens any man; with ease

He makes the strong man humble and with ease

He levels mountains and exalts the plain. (59)

Later in the poem, Hesiod would lament about the sad times in which he lived, appealing to Zeus “to set our fallen laws upright.” To show the authority of Zeus and teach his brother a lesson, Hesiod turned his attention to Prometheus, considered the craftiest of all. He had stolen fire from the gods and given it to humanity. Having earned a reputation for being vengeful, Zeus wanted to punish the arrogance of man, so he gave them “an evil thing for their delight,” Pandora.

Pandora first appeared in the Theogony although not by name. She was created in the image of an immortal goddess. Athena taught her to weave. Aphrodite gave her charm and desire. Hermes furnished her with sly manners as well as persuasive words and cunning ways. Adorned by the gods, she was given to Epimetheus (Prometheus's brother) as his wife. Prometheus had warned him not to accept any gift from Zeus, but he did not listen. Before Pandora, humans had lived free from sorrow, painful work, and disease. However, this gift from the gods became the ruin of humanity, and, according to myth, released countless evils upon the earth, leaving only hope. Hesiod concluded his lesson by saying that there was no way to escape the mind of Zeus, for according to Hesiod, Zeus was all-seeing.

The Five Races

Hesiod next spoke of the five races of humanity. Still speaking to his brother, Hesiod asked to take his tale to heart. The first race was during the time of Cronus, the golden race, and saw humans living with happy hearts without sorrow or work. They never grew old only to die peacefully in their sleep, every want was given to them. At the end of their time on earth, they were to become unseen, living as spirits of the earth.

They were replaced by the brief and far inferior silver race, a people who lived anguished lives unable to control themselves, forsaking the gods by leaving the altars bare. Zeus became angry and hid them away to become, in the words of Hesiod, the “spirits of the underworld.” The next race, the aptly named bronze, used bronze weapons and tools, even living in bronze homes.

… and they loved

The groans and violence of war; they ate

no bread; their hearts were flinty-hard; they were

Terrible men. (63)

They were thought to be invincible only to eventually die by their own hands, nameless, to join Hades, leaving the brightness of the sun. After the bronze, Zeus created a fourth race; a race of godlike heroes. This was the race before Hesiod's own time; a time of terrible wars and frightful battles. It was the time when Paris stole Helen, initiating the Trojan War. Next came the time of Hesiod – the iron race – a period of hardship and toil.

I wish I were not of this race, that I

Had died before, or had not yet been born. (64)

He said that during the day people work and grieve but at night they waste away and die. He viewed them as wretched and godless, believing Zeus would eventually destroy them all.

Advice to a brother

Hesiod spent the most of the remaining poem giving guidance to his brother. Much of the advice given to Perses centered on the benefits of the agrarian life. He opens the dialogue with a plea:

O Perses, think about these things:

Follow the just, avoiding violence.

The son of Kronos made this law for men:

That animals and fish and winged birds

Should eat each other for they have no law

But mankind has the law of Right from him,

Which is the better way. (67)

Hesiod claims that if one is just, Zeus will make him prosperous and not punish him with blight or famine; however, he will admonish those who till the fields of pride. Hesiod further lectures his brother on the evils of idleness, saying that a person who works will be the envy of others, but a greedy person who gains his wealth through lies will be punished by the gods. The best man is one who thinks for himself although he should still listen to another person's good advice. If he does not think for himself or learn from others, he is a failure as a man.

In both of his poems, Hesiod does not speak highly of women. In Works and Days, he tells his brother to not be taken in by a woman for she only wants your barn. He warns against women being a cheat and advises his brother to marry when he is ready around the age of thirty. “You must teach her sober ways.” (pg. 81) Repeating his warning from Theogony, he claims that a worthy wife is a prize, but a bad one makes a person shiver in the cold, and a greedy one will bring him “to a raw old age." While he may give his brother advice against marriage, he counsels him to get a house, a woman (a slave), and an ox for plowing, but be sure the woman is unmarried and can help in the field and around the house. Hesiod even describes in detail the plowing of the fields.

When ploughing-time arrives, make haste to plough

You and your slaves alike, on rainy days

And dry ones, while the season lasts.” (73)

Hesiod warns to be sure to offer a pray to Zeus, the farmer's god, and Demeter for her sacred grain. He also speaks of the holy days of the month that should be respected for they come from Zeus.

These days are blessings to the men on earth; The rest are fickle, bland, and bring to luck. (86)

He advises his brother not to spend time listening to gossip at the blacksmith's shop for they keep a man from work and consequently helpless and poor in winter.

The idle man who lives on empty hope

And has no way to earn a living, turns

His mind to crime: hope is not good for him

Who sits and gossips when he has no job. (75)

While he sings the praises of the farm life, he also speaks of the simpler things: owning a fleecy coat, tunic, and ox-hide boots (lined with felt). His advice is not to be too hospitable, yet one should not be seen as unfriendly. One should not be rude at a common feast, and never forget to wash hands before offering wine to the gods. Most wisely, one should never urinate towards the sun or, while traveling, along the side of the road. And, one should never eat from an unblessed pot.

Perses is reminded that all work has a season, even sailing. He should admire small ships but put his cargo in a larger one. If he must sail, he should do it after the solstice to avoid the summer heat. Hesiod tells his brother that he, himself, had sailed long ago from Aulis to Euboea. He tells of his experiences with the Muses. It was there that he was taught how to sing.

And there, I say, I conquered with a song

And carried home a two-eared tripod, which

I set up for the Muses

in that place

On Helicon, the place where I embarked

On lovely singing, first at their command. (60)

Legacy

Whether or not Perses gave up his misdirected life and followed his brother's advice is unknown. Wender believed that while Hesiod may be viewed as conservative and pessimistic, his advice to his brother is sincere and serious. In a comparison of Hesiod to his contemporary Homer, she wrote that Homer's gods were not very admirable ethically; they lied, cheated, and stole, but they were still quite civilized. Hesiod, on the other hand, let his gods remain primitive and disordered. Norman Cantor believed that both of these Dark Age poets Hesiod and Homer had a profound effect on Greek religion. Cantor wrote that the Greeks had never adopted a code of behavior or any theological beliefs. Their religion was mostly composed of myths, cults, and rituals. The Greeks accepted the perceptions presented by Homer and Hesiod's works, creating a unique Greek religion. Hesiod's poems, while forgotten by many modern readers, had an immense effect on both the Greek people of his time as well as a young poet centuries later, the Roman Ovid.