The Wounded Knee Massacre of 29 December 1890 was the slaughter of over 250 Native Americans, mostly of the Miniconjou people of the Lakota Sioux nation, by the US military at Wounded Knee Creek, South Dakota. Although the US government defined the event as a "battle", most of the Native Americans were ill, unarmed, and women and children.

The massacre was the result of rising tensions among white settlers, agents of the Bureau of Indian Affairs, and army officers concerning the Ghost Dance, a popular movement among the Plains Indians nations, which, though peaceful, was interpreted as a preparation for war. Even though a former, experienced, Indian Agent, the surgeon Valentine McGillicuddy (l. 1849-1939), explained the Ghost Dance to authorities as a religious movement, having nothing to do with a call to arms, his counsel was ignored.

Acting Indian Agent James McLaughlin (l. 1842-1923) called for more troops to be deployed to South Dakota, and these soldiers were already on the alert for an uprising as The Dawes Act of 1887 had broken up the Great Sioux Reservation to provide land to white settlers and a Sioux military response was expected.

On the morning of 29 December 1890, while the soldiers were disarming the Sioux at Wounded Knee Creek, a rifle went off and the troops surrounding the Sioux encampment opened fire. 25 US soldiers were killed, mainly through friendly fire, while between 250-300 Sioux were massacred.

Westward Expansion & Conflict

Westward expansion of the United States began as early as 1801, but increased after 1803 when President Thomas Jefferson (served 1801-1809) completed the Louisiana Purchase with the French government for a swath of land stretching from the border with Canada to New Orleans and from the Mississippi River to the Rocky Mountains. This transaction doubled the territory of the United States and invited citizens to settle out west.

It soon became apparent, however, that there were people already living in the region – who had been there for thousands of years – and who felt no obligation to surrender their land just because money had been exchanged between two governments that had nothing to do with them. Conflicts between white settlers and the Plains Indians began as early as 1810, escalating in 1823 with the First Plains Indian War (Arikara War) between the Arikara, with Sioux allies, and the US Army, and increasing from 1840-1890.

In 1845, the journalist John L. O'Sullivan (l. 1813-1895) coined the term "Manifest Destiny" in an article advocating for the U.S. annexation of the Republic of Texas. O'Sullivan repeated the vision of President Jefferson that the United States was ordained by Providence to "overspread the continent." He never called for a conquest of the land, however, as he believed citizens would settle the west peacefully, never considering the possibility that the original inhabitants of that region might object.

Massacre of the Buffalo & War

The buffalo and the Plains Indians were intimately linked as the people not only relied on the buffalo as their primary food source but considered the animal a gift from and a means of communing with the Creator. The buffalo (bison) provided the people with essential resources, besides food, as every part of the animal was used in making tools, clothing, footwear, tipis, bowls, cups, spoons, and even the string for bows.

Between c. 1840-1890, the U.S. government encouraged the extermination of the buffalo to subjugate the Plains Indians nations as well as eliminate an obstacle to the transcontinental railroad and westward expansion. There were an estimated 60 million buffalo in the region at the beginning of the 19th century and the roaming herds interfered with the laying of track and turning the prairie into grazing fields for cattle. The US government supplied arms and ammunition to hunting parties who frequently killed upwards of 100 buffalo a day. During this same time, forced relocation of Native American Nations to reservations increased as they were also seen as an obstacle to the policies encouraged by the concept of Manifest Destiny.

The Plains Indians defended the buffalo and their lands, fighting back in conflicts such as the Comanche Wars (1836-1877) and the Buffalo Hunters' War (1876-1877) among the many others now known as the Plains Indian Wars, including the Great Sioux War of 1876-1877. After the Sioux victory at the Battle of the Little Bighorn in June 1876, the US Army retaliated, driving the Sioux and their allies of the Cheyenne and Arapaho onto reservations.

The Ghost Dance

In 1869, the Paiute prophet Wodziwob (d. c. 1872), received a vision promising the people a return to their former way of life if they would live morally and practice the Spirit Dance (later mistranslated as "Ghost Dance") that would bring on a great earthquake, eliminating everyone, and then restoring the land to those who had been faithful to his vision.

After his death c. 1872, the movement died out but was revived in 1889 by Wovoka (also known as Jack Wilson, l. c. 1856-1932), the son of one of Wodziwob's followers. Wovoka preached a less apocalyptic vision in which the people would regain all that had been lost if they followed his teachings on non-violence, refrained from lying and stealing, and practiced the Ghost Dance.

He claimed to have seen the afterlife in which all those who had died were living peacefully among great herds of buffalo in a beautiful land. If the people would faithfully observe the Ghost Dance, the white men would peacefully withdraw and go back to where they had come from, the dead – and the buffalo – would return to the Great Plains, and all would be restored to how it had been.

Wovoka's vision was embraced by several Plains nations including the Caddo, the Cheyenne and Arapaho, the Iowa, Osage, Otoe-Missouria, Pawnee, Quapaw, and the Sioux. The Sioux Chief Kicking Bear (l. 1845-1904) introduced the dance to his people – and possibly the Ghost Shirt which was thought to provide supernatural protection to the wearer – and sought advice on whether the dance should be practiced from the great Sioux chief and medicine man Sitting Bull (l. c. 1837-1890). Sitting Bull granted permission for Ghost Dance observances at the Standing Rock Reservation, where he lived, but did not participate himself or advocate for the vision.

The dance was based on the Native American circle dance (round dance) traditionally performed by Native Peoples of North America as a part of social events or religious rituals. Dancers would join hands in a circle and side-step to the rhythm of drums and chanting, usually around a central fire or pole representing the sacred tree of life.

The Ghost Dance differed from the traditional circle dance as it did not always involve a central object or drums, and the dancers themselves would chant, instead of, or along with, specially designated singers. It also usually began by one or more participants throwing soil into the air, symbolizing how they would one day be taken up from the ground while the new earth was created before being set down in a world restored.

The pace of the dance increased as the chanting rose in volume and the rhythm quickened. Firsthand accounts report people falling 'dead' in a trance and waking to describe how they had seen the beautiful land Wovoka had spoken of where the buffalo still moved across the plains in great herds and all those who had died were living peacefully.

Arrest of Sitting Bull & Spotted Elk's Flight

Although Wovoka had preached non-violence, and none of the Ghost Dancers had shown any signs of aggression, the Indian Agent James McLaughlin, who supervised the Standing Rock Reservation, believed the movement was a prelude to armed uprising and a continuation of the Sioux Wars. Accordingly, he requested more troops deployed to the region.

Former Indian Agent Valentine McGillycuddy explained the dance was only a religious expression, having nothing to do with war, but McLaughlin chose to err on the side of caution and ordered the arrest of Sitting Bull, claiming he was the spiritual leader behind the movement.

On 15 December 1890, McLaughlin sent Native American police officers to Sitting Bull's home at Standing Rock to arrest him. When Sitting Bull resisted, other Sioux moved to defend him, and in the ensuing brief conflict, Sitting Bull was shot dead. Lakota Chief Spotted Elk (also known as Big Foot, l. 1826-1890), with his Miniconjou people, was at the Cheyenne River Indian Reservation at this time when Sitting Bull's Hunkpapa people brought him the news. Fearing he might be next on McLaughlin's list, Spotted Elk set off for the Pine Ridge Reservation on the night of 23 December to seek the counsel of Red Cloud (l. 1822-1909) and resolve the problems with McLaughlin peacefully.

The Massacre

The journey to Pine Ridge was slowed as many of the people were ill, traveling with small children, and Spotted Elk himself was suffering from pneumonia. After five days, the group of 350 Hunkpapa and Miniconjou Sioux were intercepted by the Seventh Cavalry on 28 December and ordered to make camp on Wounded Knee Creek. Spotted Elk and his people complied, and while they were setting up their camp, Colonel James W. Forsyth (l. 1834-1906) arrived with reinforcements and deployed his troops in a ring around the ridge surrounding the Native camp, setting up four Hotchkiss M1875 mountain guns (a lightweight precursor to the howitzer) at intervals.

On the morning of 29 December, Col. Forsyth met with a council from the camp, demanding the surrender of all weapons. While this meeting was in progress, several of the people in the camp began chanting the Ghost Dance songs while some hurled fistfuls of soil into the air to signal the start of a dance (according to some reports, the medicine man Yellow Bird alone did this or began it). The Seventh Cavalry was already on edge as, first, many of them were veterans of the Battle of the Little Bighorn and had seen the aftermath of Custer's defeat firsthand, and, second, they had been informed that the Natives were hostile following the break-up of the Great Sioux Reservation and forced relocations and so interpreted the chanting and dirt-throwing as a build-up to an attack.

Accounts of what happened next differ, but the following is now generally accepted. At the same time Forsyth was meeting with the Native council, soldiers were in the camp disarming the people, and one Sioux, Black Coyote – who was deaf – was carrying his rifle to surrender when he was accosted by a soldier demanding the weapon. Black Coyote did not hear him and so the trooper grabbed him, and he resisted. As he struggled with the soldier, the rifle discharged and the troops instantly opened fire on the camp. The Hotchkiss guns fired exploding shells, killing groups of people indiscriminately, while rifles and small arms picked off individuals who were either trying to escape or find some means of defending themselves.

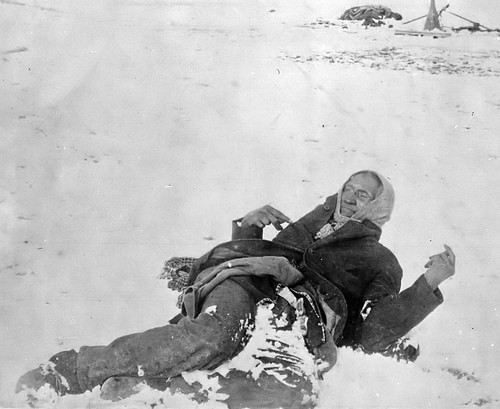

Those who managed to flee the camp were pursued, overtaken, and shot, and afterwards, bodies were found 3 miles from the camp, their positions on the ground clearly suggesting they were killed while trying to escape, not putting up any kind of resistance. Estimates of the casualties were at first given as 150 Natives but later raised to over 250, with some as high as 300. US Cavalry casualties were 25 dead, most from friendly fire.

Aftermath

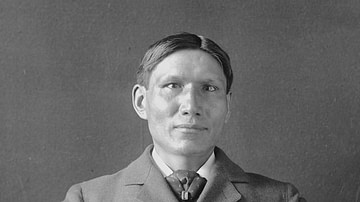

The Sioux physician and writer, Charles Eastman (also known as Ohiyesa, l. 1858-1939) went to the site of the massacre three days later with his future wife, Elaine Goodale (l. 1863-1953), traveling with the civilian burial detail, to help the wounded. He wrote an account of what he experienced which reads, in part:

At dusk, the Seventh Cavalry returned with their twenty-five dead, and I believe thirty-four wounded, most of them by their own comrades, who had encircled the Indians, while few of the latter had guns. A majority of the thirty or more Indian wounded [whom they brought back] were women and children, including babes in arms. As there were not tents enough for all, Mr. Cook offered us the mission chapel, in which the Christmas tree still stood, for a temporary hospital. We tore out the pews and covered the [cold] floor with hay and quilts. There we laid the poor creatures side by side in rows, and the night was devoted to caring for them as best we could. Many were frightfully torn by pieces of shells and the suffering was terrible.

(Townsend, 144)

The original body count among the Sioux was given at 150 because the first 146 or 150 bodies were buried in a mass grave on 3 January 1891 but, at that time, no account was made of the many more who were not interred there and were found and buried later, raising the number to above 250, among them Spotted Elk and Black Coyote.

General Nelson A. Miles (l. 1839-1925), who was sympathetic to the Sioux and had filed reports earlier in the month pointing out several failures of the government to resolve their grievances, relieved Forsyth of command, denouncing the massacre, but a Military Court of Inquiry exonerated him, and he was later reinstated. As the event was defined as a "battle" by the US government, 20 of those who participated were awarded Medals of Honor, including some who had pursued, overtaken, and killed unarmed and defenseless Lakota.

Conclusion

A three-day snowstorm buried many, but not all, of the bodies and so, when the photographers arrived with the burial detail, they captured images of the dead Lakota and horses in grotesque positions on frozen fields. These pictures did not encourage any outrage from the white population on any significant level because the event was presented by the media as a "battle" and the dead as casualties of war. The photos became popular curiosities and bestsellers back east.

The insistence of the US government that the event had been a "battle" meant that it must have taken place during a state of war, and so any deaths were casualties of war, not murder. Shortly afterwards, when the Lakota warrior Plenty Horses killed Lt. Edward Casey, he was acquitted due to this "state of war" as the government could not convict him without acknowledging the "battle" was actually a massacre of unarmed people in peacetime.

Iron Hail (also known as Dewey Beard, l. 1858-1955), who was shot three times at Wounded Knee and lost his parents, wife, and baby in the massacre, and his brother Joseph Horn Cloud (l. 1873-1920) formed the Wounded Knee Survivors Association soon after the massacre seeking compensation from the US government for injuries and casualties. They were assisted by General Miles and a government investigation into their claims was launched, finally concluding that the Lakota should be compensated $20,000.00 for loss of property taken from the site of the massacre by artifact-hunters; no mention was made of loss of life because the event was understood as a "battle" during a "state of war." The government never took any action on this, however, and preferred to let the matter settle and disappear.

In 1903, the Wounded Knee Survivors Association erected a memorial at the site which was declared a National Historic Landmark in 1965 and included on the National Register of Historic Places one year later. The event gained national attention in 1970 after the publication of the controversial bestseller Bury My Heart at Wounded Knee: An Indian History of the American West by Dee Brown. The title is taken from the last line of the 1931 poem American Names by Stephen Vincent Benet which has nothing to do with the massacre and is only an homage to the placenames of America. The line resonated, however – especially among Native Americans – owing to the memory of 29 December 1890.

The site again gained national prominence in 1973 through the Wounded Knee Occupation (also known as Second Wounded Knee), a 71-day standoff in the town of Wounded Knee, on the Pine Ridge Reservation, between members of the American Indian Movement with Sioux allies and federal law enforcement agents over corrupt administration of Indian affairs and broken treaties; neither grievance was resolved by the time the standoff ended.

The American Indian Movement consciously chose the site for its historical resonance with the inhumane policies of the US government toward Native Americans. In 1990, the US Congress passed a resolution expressing their regret for the events of 29 December 1890, but the Sioux still have not been compensated in any way for the Wounded Knee Massacre, which continues to be referenced in history books as a battle.