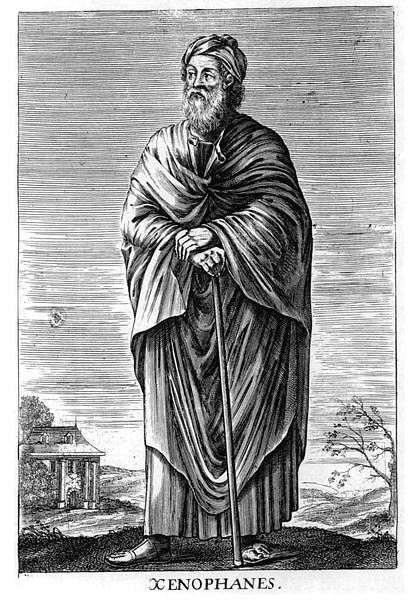

Xenophanes of Colophon (l. c. 570 to c. 478 BCE) was a Greek philosopher born 50 miles north of Miletus, a city famed for the birth of philosophy and home to the first Western philosopher, Thales of Miletus (l. c. 585 BCE). He is considered one of the most important of the so-called Pre-Socratic philosophers.

Xenophanes is regarded highly for his development and synthesis of the earlier work of Anaximander (l. c. 610-546 BCE) and Anaximenes (l. c. 546 BCE) but, chiefly, for his arguments concerning the gods. The prevailing belief of the time was that there were many gods who looked and behaved very much like mortals. Xenophanes claimed that there was only one God, an eternal being, who shared no attributes with human beings.

His thoughts on the Divine may have derived from Egyptian religion as the pharaoh Akhenaten (r. 1353-1336 BCE) had developed this monotheistic thought centuries before and, according to some scholars (and Sigmund Freud), this Egyptian model inspired the monotheism of the biblical Moses. This claim has been repeatedly challenged, however, and many scholars believe Xenophanes arrived at his conclusions independently. Evidence for this claim is suggested by the fact that none of Xenophanes' contemporaries seem to have responded positively to his monotheism and no movement supported it.

Early Life & Background

Xenophanes was from Colophon on the mainland of Anatolia (Asia Minor) and a contemporary of the philosopher Pythagoras (l. c. 571 to c. 497 BCE) who also believed that the religious beliefs of his day were incorrect and taught the doctrine of the transmigration of souls (reincarnation) and a theology, based on that doctrine, which was available only to his disciples and so discussions or definitions of his beliefs in the present-day can only be speculative.

The earlier Ionian philosophers, Anaximander and Anaximenes, were chiefly concerned with identifying the basic substance of 'being', of the reality which makes up life and the world. Anaximander identified this substance as the apeiron, the unlimited, or boundless, by which he meant something that provided the underlying form of existence. His student Anaximenes developed this theory by claiming that air was the basic substance in that air was `unlimited and boundless' but that the effects of air (wind, breath) could be observed. Instead of an invisible apeiron, then, one had an observable phenomenon for study. Anaximenes recognized that:

By rarefaction, air becomes fire, and, by condensation, air becomes, successively, wind, water, and earth. Observeable qualitative differences (fire, wind, water, earth) are the result of quantitative changes, that is, of how densely packed is the basic principle. (Baird, 12)

Xenophanes drew upon both these earlier theories but recognized in them a religious significance. The apeiron of Anaximander and the air of Anaximenes pointed, Xenophanes claimed, to a force greater than either concept as a First Cause and could, simply, be both: God - an eternal, singular, uncreated being who set all other things in motion and governed their movements since the moment of creation.

Xenophanes' God

Xenophanes writes that this God "sees all over, thinks all over, hears all over. He remains always in the same place, without moving; nor is it fitting that he should come and go, first to one place then to another. But without toil he sets all things in motion by the thought of his mind." (Robinson, 53) These claims regarding a deity were a radical departure from the anthropomorphic gods of Mount Olympus who were thought to daily interact and interfere with the lives of mortals. Xenophanes' god was transcendent, uncreated, and invisible spirit.

He dismissed the popular understanding of the gods as superstition and claimed that the traditional understanding of the deities based on the writings of Hesiod and Homer (both l. c. 8th century BCE) was wrong, stating:

Homer and Hesiod ascribed to the gods whatever is infamy and reproach among men: theft and adultery and deceiving each other. (Baird, 17)

Xenophanes argued that the transcendent nature of God was easily apprehended in the natural world and the Supreme Deity did not need fictions to explain itself when it had already provided simpler prompts to recognizing its creation. Whereas the rainbow, in Greek belief, was considered a manifestation of the goddess Iris, Xenophanes claimed that, "She whom men call 'Iris' is in reality a cloud, purple, red, and green to the sight." (Robinson, 52). He further argued:

Mortals suppose that the gods are born and have clothes and voices and shapes like their own. But if oxen, horses and lions had hands or could paint with their hands and fashion works as men do, horses would paint horse-like images of gods and oxen oxen-like ones, and each would fashion bodies like their own. The Ethiopians consider the gods flat-nosed and black; the Thracians blue-eyed and red-haired. There is one god, among gods and men the greatest, not at all like mortals in body or mind. (Diogenes Laertius, Lives)

While this may seem a familiar theological understanding in the modern day, it was by no means a common concept in Xenophanes' time. He seems to have framed his one God alongside the accepted pantheon of the many deities of Greece in order to make the concept more palatable to his audience. Though he consistently speaks of 'many gods' it is clear that he does not believe they exist anywhere but in the minds of people.

He notes, for example, how "mortals suppose that the gods are born and have clothes and voices and shapes like their own" while clearly mocking and deriding this belief as childish (Baird, 17). Such claims were a serious offense at the time, however, and Xenophanes could have included his references to many gods simply as a way of avoiding trouble as he clearly thought the concept ridiculous.

Xenophanes & Plato

Later writers, perhaps influenced by two passing characterizations of Xenophanes by Plato (Sophist 242c-d) and Aristotle (Metaphysics 986b18-27) identified him as the founder of the Eleatic School of philosophy which claimed that, despite the illusion of the senses, what exists is really a changeless, motionless, and eternal One. This view has been largely rejected, however, and Xenophanes is now seen as a lone figure criticisizing the anthropomorphic deities of his time (with Parmenides, rightfully, acknowledged as the founder of the Eleatic school of philosophy).

Even so, Xenophanes was said to have been Parmenides' teacher and the two philosophers share the fundamental concept that existence comes from a single, unifying force. As Xenophanes puts it:

There is one god, among gods and men the greatest, not at all like mortals in body or mind. He sees as a whole, thinks as a whole, and hears as a whole. He always remains in the same place, not moving at all, nor is it fitting for him to change his position at different times. (Baird, 18)

According to Xenophanes, recognition of this force enables one to obtain a clearer and more precise understanding of the world and one's place in it. This line of thought would later be explored more completely in Plato's dialogues. Plato emphasizes this concept through his discussion of the "true lie" (also known as The Lie in the Soul) in Book II of his Republic. In this passage, Plato claims that what people hate the most is to believe wrongly about the most important aspects of one's life. This concept, as well as Plato's famous Theory of Forms - which claims an objective, external, higher realm of Truth which makes all things which one values on earth true - can be traced back to the work of Xenophanes.

Legacy

Xenophanes traveled widely, reciting his poetry and, in so doing, spread his beliefs. Among these was his recognition of the relativity and limitation of human understanding. He writes, "The gods have not revealed all things from the beginning to mortals but, by seeking, men find out, in time, what is better" (Robinson, 56). It is only by searching for the truth that one will find that truth. According to Xenophanes, one should not simply accept the beliefs of one's community as `truth' without questioning the validity of the concepts held.

Xenophanes' claim most certainly influenced later writers, most notably Socrates and, after him (as noted), Plato. Both of these later philosophers insisted on pursuing an individual course in pursuit of truth and wisdom. Xenophanes' concept of the one God, as noted above, influenced Parmenides' and the Eleatics' recognition of unity and their work contributed to Plato's Theory of Forms and Aristotle's Unmoved Mover, providing a philosophical basis for the development of monotheism.

Though quite different in specifics, Plato's Forms and Aristotle's Unmoved Mover both posit the existence of a 'higher' realm of reality which is responsible for the observable world. Xenophanes most likely would have approved of both these theories but, in keeping with his insistence on the small scope of human understanding, would have suggested both approached truth without being actually true. Xenophanes did not even consider his own views to be objectively true, only more valid than the beliefs of those around him.

Regarding his teaching, he writes, "Let these things, then, be taken as like the truth" not as truth itself. Only the one God knows the Truth, Xenophanes claimed, and mortals can only approach, never fully grasp, what that truth is. Different people and different cultures will interpret the Ultimate Truth differently but these, in the end, are simply reflections of the Truth which is only known to itself.