Xunzi (pronounced shund-zee, l. c. 310-c. 235 BCE) was a Confucian philosopher of the Warring States Period (c. 481-221 BCE) in China. He is also known as Hun Kuang, Hsun Tzu, Xun Tzu, and Xun Kuang. Xunzi translates as Master Xun and is also the name of the book (the Xunzi) which has established his enduring reputation.

Xunzi is the greatest reformer of Confucian thought after Mencius and the last of the Five Great Sages of Confucianism:

- Confucius (l. 551-479 BCE)

- Zengzi (l. 505-435 BCE)

- Tzu-Ssu (also given as Zisi, l. c. 481-402 BCE)

- Mencius (l. 372-289 BCE)

- Xunzi (l. c. 310-c. 235 BCE)

Confucianism developed initially as just one of many philosophies during the era of the Hundred Schools of Thought of the Spring and Autumn Period (c. 772-476 BCE) which preceded the Warring States Period. Confucius developed his system from the cultural works of the Zhou Dynasty (1046-256 BCE) which was in decline during his lifetime. It was then developed by his student Tzu-Ssu and grandson Zisi until it was thought to be fully articulated by Mencius.

Xunzi, however, disagreed with some fundamental Mencian concepts and reformed the system further. He came to be regarded as the leading philosopher of his day but later lost status due to his association with two of his students, Han Feizi (l. c. 280-233 BCE) and Li Siu (also given as Li Si, l. c. 280-208 BCE). Han Feizi developed the philosophy of Legalism which informed the repressive regime of the Qin Dynasty (221-206 BCE) which rose after the state of Qin conquered the others and ended the Warring States Period. Afterwards, Li Siu served as prime minister to that regime's first emperor Shi Huangdi (r. 221-210 BCE) and his successor. The reign of the Qin was so oppressive, brutal, and ultimately destructive that anyone associated with it shared in its poor reputation, and so it was with Xunzi.

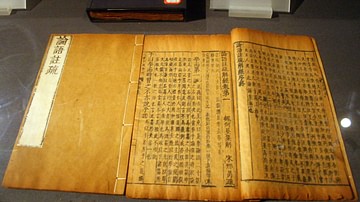

His views were known by the early Han Dynasty (202 BCE-220 CE), which succeeded the Qin and would adopt Confucianism as the state philosophy, but his work, the Xunzi, was lost and most likely thought destroyed by the Qin, until its rediscovery by the scholar Liu Xiang (l. 79-8 BCE), an imperial palace librarian who collected and organized the chapters and wrote a commentary on it. Xunzi's pragmatic vision of the nature of human existence and his denial of supernatural influences not only influenced Confucianism but prefigured later philosophical movements in other cultures. He is recognized in the present day for completing the Confucian system as well as for his reputation as one of the most important philosophers in world history.

Historical Background & Life

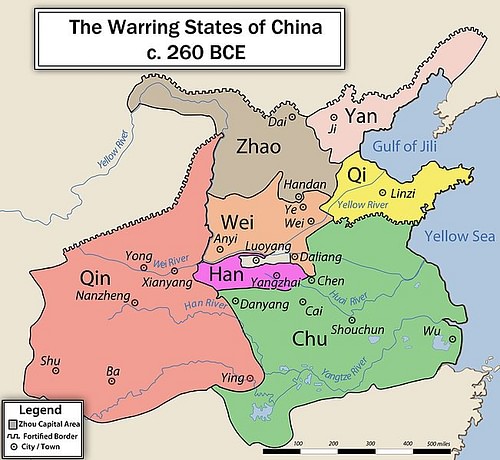

Xunzi lived during one of the most violent and chaotic times in China's history. The Zhou Dynasty was in decline during the Spring and Autumn Period and the states which were once under its control now sought to assert themselves and gain supremacy. The Zhou had enacted a policy of decentralization of government under which separate states, loyal to the king, ruled almost autonomously. When the royal house began losing its grip on these states, the stronger began to absorb the weaker until there were seven states – Chu, Han, Qi, Qin, Wei, Yan, and Zhao – who, during the Warring States Period, battled each other almost constantly for control.

Almost nothing is known of Xunzi's life and his dates are an approximation. Most scholars agree on a birth date of c. 310 BCE but any information on his life is sparse and comes from Liu Xiang's compilation of the Xunxi and from the Records of the Grand Historian (c. 94 BCE) by Sima Qian (l. 145/135-86 BCE) which preserved his reputation.

Xunzi eventually arrived in the state of Qin, possibly as a prospective candidate for government work or maybe just as a visitor. As with the rest of his life, nothing is known of why he was there or what he did. It is thought that, as with the other states, he tried to convince the Qin to adopt Confucianism and may have taught (officially or unofficially) at a school. It is at this time that he might have directly taught Han Feizi of Qin, the later founder of Legalism, and Li Si, the future prime minister of the Qin Dynasty, an association which would later tarnish his reputation.

Following some unspecified problem in Qin, he traveled to the state of Chu where he was given the position of Magistrate of Lanling by Lord Chunshen (d. 238 BCE), prime minister of Chu. Lord Chunshen was assassinated in 238 BCE and Xunzi's position was given to another of the rival faction responsible. He stayed in Chu until his death which is usually given as c. 235 BCE although it is also claimed he lived to see the rise of the Qin Dynasty and the roles Han Feizi and Li Si would play in the formation of governmental policy. This claim puts his death at c. 219-218 BCE which is generally rejected by scholars.

The form of Confucianism he taught is thought to have been the same which appears in his book, Xunzi; a pragmatic and, according to some views, far more pessimistic interpretation of the Confucian vision than its founder, or the earlier sages, had offered.

Confucianism Pre-Xunzi

The Confucian system at first developed, along with many others, during the Spring and Autumn Period in the era known as the Hundred Schools of Thought. As the Zhou Dynasty collapsed, teachers and scholars who had previously held government posts were unemployed. These intellectuals sought jobs elsewhere, or set up their own schools, teaching their specific systems which, more or less, were a direct reaction to the incessant warfare and instability of the time.

Of the many schools which contended with each other for acceptance during this time, 14 are considered noteworthy:

- Confucianism

- Taoism

- Legalism

- Mohism

- School of Names

- Yin-Yang School

- School of Minor Talks

- School of Diplomacy

- Agriculturalism

- Syncretism

- Yangism (Hedonist School)

- Relativism

- School of the Military

- School of Medicine

As time went on, each of these would borrow from the others to greater or lesser degrees but the three which would eventually become most influential were Confucianism, Taoism, and Legalism. Confucianism maintained that people were essentially good but needed instruction, encouragement, and role models in order to express that goodness. Taoism claimed that people misbehaved because they were out of touch with nature and need only align themselves with the cosmic force of the Way (Tao) in order to live and behave well. Legalism rejected both these visions and argued that people were driven solely by self-interest and selfishness and so strict laws were required to control their impulses and maintain an ordered society.

Confucianism and Taoism shared a common concept in that there was a divine or higher power which influenced the lives of people; in Confucianism, this was Tian (Heaven) in Taoism is was the Tao (Way). Confucianism always seems to have had a strong element of Legalism to it but emphasized personal virtue over laws in the encouragement of good behavior. The texts Confucius worked from were:

- The I-Ching

- The Classics of Poetry

- The Classics of Rites

- The Classics of History

- The Spring and Autumn Annals

After absorbing the lessons and models of these texts, one adhered to a philosophy of personal integrity and social responsibility through a code of ethics defined as the Five Constants and Four Virtues:

- Ren – benevolence

- Yi – righteousness

- Li – ritual

- Zhi – knowledge

- Xin – integrity

- Xiao – filial piety

- Zhong – loyalty

- Jie – contingency

- Yi – justice/righteousness

This was the system developed by Confucius and his first two successors. Mencius streamlined the Confucian vision and, while acknowledging the Five Constants and Four Virtues, paired them down to a basic four:

- Ren – benevolence/humaneness

- Yi – righteousness/goodness

- Zhi – knowledge/wisdom

- Li – propriety/proper ritual

These are known as the Four Seeds of Mencius which are so-called because he believed these virtues were inherent in all people and only needed proper encouragement to sprout and bloom, allowing one to reach one's full potential as a superior human being, referenced as a junzi, translated as “gentleman”.

By this illustration, Mencius claimed, one could recognize the inherent goodness of human beings. People only behaved badly due to an overdeveloped sense of self-interest which encouraged selfish and prideful behavior. All one needed to do to live a better, more fulfilled, and more socially interactive existence was to embrace the Confucian ideals and nurture the Four Seeds each person has within themselves.

Mencius added the works attributed to Confucius to the Confucian curriculum – The Book of Rites, The Doctrine of the Mean, and The Analects of Confucius – and, after his death, The Works of Mencius was also added. These four, and the earlier five Confucius worked from, became known as the Four Books and Five Classics and would become required reading for educated Chinese.

Xunzi's Reforms

This was Confucianism after Mencius' reforms but Xunzi would take the reformation further. Scholar Forrest E. Baird comments:

The first breech in the Confucian school opened up between the right-wing idealistic school of Mencius and Xunzi's left-wing realistic school. As fellow Confucians, they shared much in common, including the Gentleman ideal, emphasis on Benevolence and Righteousness, reliance on education as the main transformative power in people's lives, esteem for the ancient Rites, the principle of the rectification of names, and belief in humane government. (294)

Xunzi departed from the vision of Confucianism's founder and reformer on their two most central concepts. He maintained:

- There is no Higher Power which influences human thought, character, or behavior.

- Human nature is not essentially good; people are innately evil, self-centered, and base in their instincts.

Xunzi dismissed the concept of Tian-as-Influence noting how, whether one prayed for rain or did not, rain would fall – or would not – in accordance with the weather pattern of a given season. If one prayed for rain, and rain fell, one thanked the divine forces; if one prayed for rain and none came, one was disappointed and frustrated. Either response was equally unreasonable because Heaven had nothing whatsoever to do with rainfall. Xunzi emphasized the concept of Constancy: nature always behaved according to set, observable, patterns. On a day in which rain was likely, it was reasonable to expect rain; on another, it was not.

He also rejected the claim of innate human goodness on the grounds that it was obvious people had to be taught to be good, but no one had to teach anyone to be self-serving and selfish. If people were essentially good, there would not have been a need for the development of a Hundred Schools of Thought to tutor them in how to live harmoniously with each other. On the contrary, Xunzi said, people require the kinds of rituals and educational programs Confucianism encouraged precisely because they were far from being naturally inclined to goodness.

Xunzi would argue against Mencius' boy-in-the-well illustration by noting there could be many reasons why someone would try to save the boy. Perhaps the boy was yelling, and the screams were annoying, perhaps the person did not want the well poisoned by the boy's corpse, maybe the person expected a reward for saving the child, or possibly the person mistook the child for one of their own. There was no reason to assume that someone was acting selflessly out of an innate goodness, then, when it was far more likely they were acting out of their own self-interest.

Even so, Mencius and Xunzi agreed that people could become good by adherence to ritual and a discipline of self-improvement. Even though Xunzi rejected Mencius' central claim regarding human nature, he approved of the concept of the Four Seeds in that, by observing rituals which encouraged these virtues, one could become a superior human being.

Although the concept of Tian as influencing human behavior was rejected, the existence of a Way (Tao) was acknowledged by Xunzi:

The Way is not the Way of Heaven, nor the Way of Earth; it is what people regard as the Way, what the noble man is guided by. (Xunzi, 8.3)

The early sages who established the concepts of virtue did not “receive” them from some divine source but came to understand them through trial and error. Xunzi uses the example of the first people to ford a river or stream leaving markers for those who follow after on which places are deep, and should be avoided, and which are surer footing. A natural Way, he claims, does exist but it has to do with nature, not with human destiny; humans direct human destiny.

If one wishes one's crops to grow, one should observe proper planting procedures so they will be watered at appropriate times; one should not pray for a good crop and leave it at that. Signs and portents from the heavens should be safely ignored, Xunzi claimed, because they could not possibly have anything to do with one's life.

Xunzi agreed with Mencius and Confucius, however, on the importance of precise language as a proper reflection of reality. In this, Confucianism was most likely influenced by the School of Names (mentioned above as one of the 100 Schools) founded by the logicians Hui Shih (l. c. 380-c.305 BCE) and Kung-sun Lung (b. c. 380 BCE) whose primary focus was on how well words corresponded to the concepts they represented – how well, for example, the word “cup” reflected the object known as a “cup”. One should use language carefully and precisely, Xunzi argued, in order to prevent one's self from misrepresenting objective reality. The purpose of language was to communicate, and so precise vocabulary was most important.

Xunzi also agreed on the goal of self-realization in becoming a junxi and how governments should care for the improvement of all the citizens; not just the luxury and comfort of the upper classes. In this, and many other aspects, Xunzi's vision was quite close to that of Mencius'. Even considering the central concepts on which they diverge, their final goal is the same: the improvement of the individual character through education and self-discipline.

Conclusion

The Four Books and Five Classics were retained by Xunzi as was the basic expression of the Confucian ideal through ritual and behavior. The importance of his reforms was his introduction of a wholly pragmatic approach to concepts which had previously been largely idealistic. After the Qin came to power, the regime was criticized by Confucian scholars who may – or may not – have been observing Xunzi's version of the philosophy. The regime responded by condemning all the works of the Hundred Schools of Thought except for Legalism and burning their books between 213-210 BCE. Xunzi's work would have met this same fate but was preserved, along with other works, by people who resisted the regime and hid the books.

After the fall of the Qin, Li Si and Han Feizi – known to have been either students of or influenced by Xunzi – were regarded poorly, to put it mildly, and Xunzi's reputation suffered. It would seem both of them only really responded to his views on human nature and neglected the rest. Han Feizi's Legalism begins with innate human selfishness as its foundational concept but offers no means of improving that condition, only restraining and punishing it; Li Si fully implemented Han Feizi's vision.

Confucianism was adopted as the state philosophy by the Han Dynasty during the reign of Wu the Great (r. 141-87 BCE), under whom Sima Qian lived and wrote. His Records of the Grand Historian informed people's opinion of Xunzi until Liu Xiang's publication of the Xunzi at some point prior to Liu's death in 8 BCE. Xunzi's reputation seems to have improved after this point but his philosophy was later marginalized in favor of Mencius' vision.

Xunzi's advocacy of a realistic, pragmatic approach to the circumstances of life still influenced Confucian thought and practice, however, as well as anticipating later philosophical movements such as Empiricism and Existentialism. His contributions to Confucianism certainly balanced but, in many ways, outweighed those of Mencius in providing people with a practical understanding of how the world works and how best to live in it.