Yahweh is the name of the state god of the ancient Kingdom of Israel and, later, the Kingdom of Judah. His name is composed of four Hebrew consonants (YHWH, known as the Tetragrammaton) which the prophet Moses is said to have revealed to his people and is sometimes given in English as "Jehovah."

The meaning of the name has been interpreted variously as "I am", "He That Is", "He Who Makes That Which Has Been Made" (Yahweh-Asher-Yahweh), "He Brings the Hosts Into Existence" (Yahweh-Teva-`ot) and, according to the philosopher Rabbi Moses Maimonides (l. 1138-1204), denotes "absolute existence" or "the totality of existence."

As the name of the supreme being was considered too holy to be spoken, the consonants YHWH were used to remind one to say the word 'adonai' (lord) in place of the god's name, a common practice throughout the Near East in which epithets were used in referencing a deity. All of these stipulations and details were applied to the god later, however; it is unclear exactly when Yahweh was first worshipped, by whom, or how. Scholars J. Maxwell Miller and John H. Hayes write:

The origins of Yahwism are hidden in mystery. Even the final edited form of Genesis – II Kings [in the Bible] presents diverse views on the matter. Thus Genesis 4:16, attributed by literary critics to the so-called `Yahwistic' source, traces the worship of Yahweh back to the earliest days of the human race, while other passages trace the revelation and worship of Yahweh back to Moses [in the Book of Exodus]. (111)

Scholar Nissim Amzallag, of Ben-Gurion University, disagrees with the claim that Yahweh's origins are obscure and argues that the deity was originally a god of the forge and patron of metallurgists during the Bronze Age (c. 3500-1200 BCE). Amzallag specifically cites the ancient copper mines of the Timna Valley (in southern Israel), biblical and extra-biblical passages, and similarities of Yahweh to gods of metallurgy in other cultures for support.

Although the Bible, and specifically the Book of Exodus, presents Yahweh as the god of the Israelites, there are many passages which make clear that this deity was also worshipped by other peoples in Canaan. Amzallag notes that the Edomites, Kenites, Moabites, and Midianites all worshipped Yahweh to one degree or another and that there is evidence the Edomites who operated the mines at Timnah converted an earlier Egyptian temple of Hathor to the worship of Yahweh.

Although the biblical narratives depict Yahweh as the sole creator god, lord of the universe, and god of the Israelites especially, initially he seems to have been Canaanite in origin and subordinate to the supreme god El. Canaanite inscriptions mention a lesser god Yahweh and even the biblical Book of Deuteronomy stipulates that “the Most High, El, gave to the nations their inheritance” and that “Yahweh's portion is his people, Jacob and his allotted heritage” (32:8-9). A passage like this reflects the early beliefs of the Canaanites and Israelites in polytheism or, more accurately, henotheism (the belief in many gods with a focus on a single supreme deity). The claim that Israel always only acknowledged one god is a later belief cast back on the early days of Israel's development in Canaan.

The meaning of the name Yahweh, as noted, has been interpreted as “I Am” or “He That Is”, though other interpretations have been offered by many scholars. In the late Middle Ages, `Yahweh' came to be changed to `Jehovah' by Christian monks, a name commonly in use today.

The character and power of Yahweh were codified following the Babylonian Captivity of the 6th century BCE and the Hebrew scriptures were canonized during the Second Temple Period (c. 515 BCE-70 CE) to include the concept of a messiah whom Yahweh would send to the Jewish people to lead and redeem them. Yahweh as the all-powerful creator, preserver, and redeemer of the universe was then later developed by the early Christians as their god who had sent his son Jesus as the promised messiah and Islam interpreted this same deity as Allah in their belief system.

Extra-biblical Mention of Yahweh

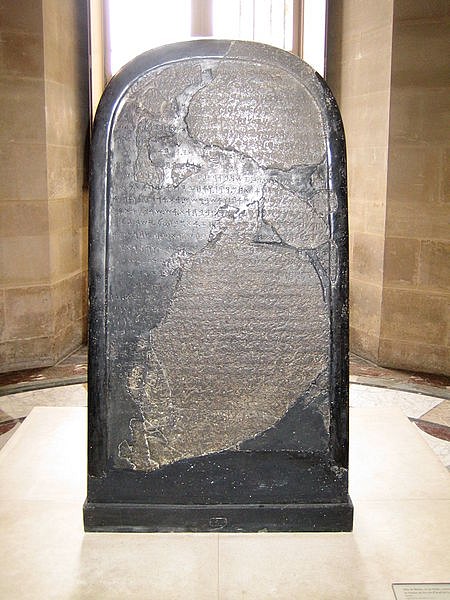

The oldest mention of Yahweh was long held to be the Moabite Stone (also known as the Mesha Stele) erected by King Mesha of Moab to celebrate his victory over Israel in c. 840 BCE. The inscription mentions how Mesha, after defeating the Israelites, “took the vessels of Yahweh to Kemosh” (the chief god of Moab), meaning the objects sacred to the worship of Yahweh in the temple, most likely the temple in Israel's capital of Samaria (Kerrigan, 78-79).

The Moabite Stone was discovered in 1868 in modern-day Jordan and the find published in 1870. As the first extra-biblical inscription found to mention Yahweh, much was made of the discovery as the stele reported the same event from the biblical narrative of II Kings 3 in which Mesha the Moabite rebels against Israel (though with the major difference of the stele claiming a Moabite victory and the Bible claiming Israel the winner). The way the Yahweh line was interpreted further supported the concept of Yahweh as the god of the Israelites alone since Mesha claims to have taken the Israelite god's vessels as tribute to his own.

In 1844, the ruins of the ancient city of Soleb in Nubia were excavated by the archaeologist Karl Richard Lepsius who documented the site in detail but did not excavate. In 1907, James Henry Breasted arrived and photographed the site but, again, engaged in no excavation. It was not until 1957 that a team under the archaeologist Michela Schiff Giorgini, excavated the site and found reference to a group of people described as “Shasu of Yahweh” at the base of one of the columns of the temple in the hypostyle hall. The temple was built by Amenhotep III (r. 1386-1353 BCE) and the reference to Yahweh established that this god was worshipped by another people long before the time when the events of the biblical narratives are thought to have taken place.

The Shasu (also given as Shashu) were a Semitic, nomadic people described as outlaws or bandits by the Egyptians and, in fact, they are named on the column of the temple at Soleb among Egypt's other enemies and appear later, in an inscription from the reign of Ramesses II (r. 1279-1213 BCE), as among the pharaoh's enemies at the Battle of Kadesh.

As it has been established they were a nomadic people, attempts have been made to link them with the Hebrews and with the Habiru, a group of renegades in the Levant, but these claims have been refuted. Whoever the Shasu were, they were not Hebrew and the Habiru seem to be Canaanites who simply refused to conform to the customs of the land, not a separate ethnic group.

The discovery of Amenhotep III's mention of the Shasu of Yahweh placed the god much earlier in history than had been accepted previously but also suggested that Yahweh was perhaps not native to Canaan. This fit with the theory that Yahweh was a desert god whom the Hebrews adopted in their exodus from Egypt to Canaan. The descriptions of Yahweh appearing as a pillar of fire by night and cloud by day as well as the other fire-imagery from the Book of Exodus were interpreted by some scholars as suggesting a storm god or weather-deity and, particularly, a desert god since Yahweh is able to direct Moses to water sources (Exodus 17:6 and Numbers 20). It is generally accepted in the modern day, however, that Yahweh originated in southern Canaan as a lesser god in the Canaanite pantheon and the Shasu, as nomads, most likely acquired their worship of him during their time in the Levant.

The Moabite Stone has also been reinterpreted in light of recent scholarship which demonstrates that the people of Moab also worshipped Yahweh and the reference to Mesha taking the vessels of Yahweh to Kemosh most likely means he repossessed what he felt belonged to the Moabites, not that he conquered Israel and its god in the name of his own.

Yahweh in the Bible

The Bible does mention other nations worshipping Yahweh and how the god arrived from Edom to help the Israelites in warfare (Deuteronomy 33:2, Judges 5:4-5) but this is not the central narrative. In the Bible, Yahweh is the one true God who creates the heavens and the earth and then chooses a certain people, the Israelites, as his own.

Yahweh creates the world, and hangs the sun and the moon in the heavens, as the Book of Genesis opens. He creates animals and human beings, destroys all in a great flood except Noah, Noah's family, and the animals Noah saves, and elects Abram (later known as Abraham) to lead his people to the land of Canaan and settle there (Genesis 1-25).

Abraham's initial community was developed by his son Isaac and then his grandson Jacob (also known as Israel). Jacob's favorite son, Joseph, was sold by his brothers into slavery and brought to Egypt where, owing to his skill in interpreting dreams, he rose to prominence and was able to save the region from famine (Genesis 25-50). The Book of Genesis concludes with Joseph dying after telling his brothers that Yahweh will bring them out of Egypt and back to the land promised to Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob.

Many years later, when the Israelites have grown too populous for the Egyptians, an unnamed pharaoh orders them to be enslaved and makes their lives harsh (Exodus 1-14). Even so, the Israelite population continues to grow and so pharaoh orders all male infants killed (Exodus 1:15-22). A woman of the Levite tribe among the Israelites hides her son and then sends him downriver in a basket to be found by pharaoh's daughter, who adopts him; this child is Moses (Exodus 2:1-10). Moses learns his true identity as an Israelite and, after killing an Egyptian, flees to the land of Midian where, in time he encounters Yahweh in the form of a burning bush (Exodus 3, 4:1-17). The rest of the Book of Exodus details the Ten Plagues which Yahweh sends on Egypt and how Moses leads his people to freedom.

Moses never reaches the promised land of Canaan himself owing to a misunderstanding he has with Yahweh in which he strikes a rock for water when he was not supposed to (Numbers 20) but he turns over leadership to his right-hand-man Joshua who then leads his people in the conquest of Canaan as directed by Yahweh. Once the land is conquered, Joshua divides it among his people and, in time, they establish the Kingdom of Israel.

Yahweh in the Canaanite Pantheon

The biblical narrative, however, is not as straightforward as it may seem as it also includes reference to the Canaanite god El whose name is directly referenced in Israel (He Who Struggles with God or He Who Perseveres with God). El was the chief deity of the Canaanite pantheon and the god who, according to the Bible, gave Yahweh authority over the Israelites:

When the Most High [El] gave to the nations their inheritance, when he separated the sons of men, he fixed the bounds of the peoples according to the number of the Sons of God. For Yahweh's portion is his people, Jacob his allotted heritage. (Deuteronomy 32:8-9, Masoretic Text).

The Canaanites, like all ancient civilizations, worshipped many gods but chief among them was the sky-god El. In this passage from Deuteronomy, El gives each of the gods authority over a segment of the people of earth and Yahweh is assigned to the Israelites who, in time, will make him their supreme and only deity; but it is clear he existed beforehand as a lesser Canaanite god.

Yahweh as God of Metallurgy

According to scholar Nissim Amzallag, however, Yahweh was a god of metallurgy. Amzallag writes:

An essential link between Yahweh and copper is suggested in the Book of Zechariah where the dwelling of the God of Israel is symbolized by two mountains of copper (Zech. 6:1-6). In his prophecies, Ezekiel describes a divine being as `a man was there, whose appearance shone like copper' (Ezek. 40:3), and in another part of this book, Yahweh is even explicitly mentioned as being a smelter (Ezek. 22:20). In Isaiah 54:16, Yahweh is explicitly mentioned as the creator of both the copperworker and his work…Such an involvement of Yahweh is never mentioned elsewhere for other crafts or human activities. (394)

Amzallag further notes the similarities between Yahweh and other gods of metallurgy:

The god of metallurgy generally appears as an outstanding deity. He is generally involved in the creation of the world and/or the creation of humans. The overwhelming importance of the god of metallurgy reflects the central role played by the copper smelters in the emergence of civilizations throughout the ancient world. (397)

Amzallag compares the attributes of the Egyptian Ptah and the Mesopotamian Ea/Enki along with Napir of Elam, all gods of metallurgy (among their other attributes) with Yahweh and finds striking similarities. He further claims that the name of the god of the Edomites, Qos, is an epithet for Yahweh and notes how the Edomites, a people closely associated with metallurgy, were the primary workers and administrators of the copper mines at Timna and, further, that Edom is never mentioned in the Bible as challenging Israel in the name of a foreign god; thus suggesting that the two peoples worshipped the same deity (390-392).

Although Amzallag's theory has been challenged, it has not been refuted. Particularly compelling are his arguments from biblical passages and the archaeological evidence cited from the ruins of the mines of Timna.

From God of Metallurgy to Supreme Deity

Yahweh, according to Amzallag, was transformed from one god among many to the supreme deity by the Israelites in the Iron Age (c.1200-930 BCE) when iron replaced bronze and the copper smelters, whose craft was seen as a kind of transformative magic, lost their unique status. In this new age, the Israelites in Canaan sought to distance themselves from their neighbors in order to consolidate political and military strength and so elevated Yahweh above El as the supreme being and claimed him as their own. His association with the forge, and with imagery of fire, smoke, and smiting, worked as well in describing a god of storms and war and so Yahweh's character changed from a deity of transformation to one of conquest. Miller and Hayes comment:

Perhaps the most noticeable characteristic of Yahweh in Israel's early poetry and narrative literature is his militancy. The so-called “Song of the Sea” in Exodus 15:1-18 and the “Song of Deborah” in Judges 5 are typical in their praise of Yahweh, the divine warrior who could be counted on to intervene on behalf of his followers…Thus it may have been primarily in connection with Israel's wars that Yahweh gained status as the national god. During times of peace, the tribes will have depended heavily on Baal in his various local forms to ensure fertility. But when they came together to wage war against their common enemies, they would have turned to Yahweh, the divine warrior who could provide victory. (112)

Yahweh-as-warrior is evident throughout the Hebrew scriptures which became the Christian Old Testament and warrior imagery is also apparent in passages in the New Testament which drew on the earlier works (ex: Ephesians 6:11, Philippians 2:25, II Timothy 2:3-4, I Corinthians 9:7, among others). By the time these works were written, the worship of Yahweh had undergone a dramatic transformation from what it had been in the early days of the Israelites in Canaan.

Early & Later Religious Belief & Practice

Initially, the people of Canaan, including the Israelites, practiced a form of ancestor worship in which they venerated the “god of the father” or the “god of the house”, in addition to paying homage to their earthly ancestors, in an effort to establish individual tribal and family connections (van der Toorn, 177). In time, this practice evolved into worship of deities such as El, Asherah, Baal, Utu-Shamash, and Yahweh among others.

As the Israelites developed their community in Canaan, they sought to distance themselves from their neighbors and, as noted, elevated Yahweh above the traditional Canaanite supreme deity El. They did not, however, embrace monotheism at this time. The Israelites remained a henotheistic people through the time of the Judges, which predates the rise of the monarchy, and throughout the time of the Kingdom of Israel (c.1080-c. 722 BCE).

In 931 BCE, following the death of Solomon, the kingdom split in two and a new political entity, the Kingdom of Judah with its capital at Jerusalem, emerged in the south. The kingdoms of Israel and Judah periodically warred or allied with each other until 722 BCE when the Assyrians destroyed Israel and, in keeping with their usual military policies, deported the inhabitants and replaced them with others from their empire. Judah was able to withstand the Assyrian military campaigns but only by paying tribute to Assyria.

The Assyrian Empire fell to an invading force of Babylonians, Medes, and others in 612 BCE and the Babylonians claimed the region of Canaan. In 598 BCE they invaded Judah and sacked Jerusalem, destroying the temple of Solomon and taking the leading citizens back to Babylon. This is the time in Jewish history known as the Babylonian Captivity (c. 598-538 BCE). Babylon was conquered by Cyrus the Great (d. 530 BCE) of the Persians who allowed the Jewish leaders to return to their homeland in 538 BCE.

As with all ancient religions (as well as modern), the faith of the people was based on an understanding of quid pro quo (this-for-that) in which they would honor and serve a deity and, in return, would receive protection and guidance. When the temple was destroyed and the kingdom sacked, the Jewish clergy had to find some reason for the tragedy and concluded it was because they had not paid enough attention to Yahweh and had angered him through the acknowledgement and worship of other gods.

During the Second Temple Period (c.515 BCE-70 CE) Judaism was revised, the Torah canonized, and a new understanding of the divine established which today is known as monotheism – the belief in a single deity. At this time, scholars have established, the older works which eventually became the Hebrew Scriptures were revised to reflect a monotheistic belief system among the Israelites far earlier than was actually practiced.

The monotheism of the Hebrew Scriptures would later be appropriated by the adherents of Christianity who would continue veneration of Yahweh, eventually known as Jehovah and then, simply, as “God”, and Islam would also develop the deity under the name of Allah (“the God”) beginning in the 7th century CE. Whoever Yahweh was originally, and however he was worshipped, today he forms the basis of the three great monotheistic religions of the world.